Words Liam Friary and Travis Brown

Images Cameron Mackenzie

Skipping our winter on a recent trip to America, I got the opportunity to not only sit down with, but ride and hang out with, the mountain bike icon, Travis Brown. The man – or, more aptly put: legend – doesn’t need much introduction, but for the new kids on the block here’s a brief history.

From the early 90’s, Travis Brown’s professional riding career left an undeniable mark on the sport. He was a regular on the World Cup circuit and claimed multiple national championships in both cross-country and marathon disciplines. At the pinnacle of his racing career, Travis represented the USA in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. After his pro career started to wind up in the mid-2000’s, his attention turned to product development with Trek. These days, he’s the field test manager, running an entire crew of riders who are working on products that we’ll see in the future.

This is the candid conversation I transcribed whilst on a weather hold between a busy riding schedule in Travis’ hometown of Durango, Colorado, in the USA.

Let’s start from the beginning: where did it all begin, for you?

“Well, I grew up in Durango. And went through, you know, student athlete life here — the local junior high school and high school. I did all the ball sports for a while, and Junior High track and cross country (running). Then started focusing on track, like, endurance sports, and did that through high school. I think, like a lot of young people with prestige or hype, whichever term you want, with the Olympic games and professional athletics, that was an aspirational thing — kind of a silly thing — but something that was stuck in my head.”

From an early age?

“Yeah. Running was the first thing where I thought, maybe I’m good enough to dream about that. And that ended early on with some chronic Achilles tendon issues. So, at that point, I changed my focus to cross country skiing. This was in high school. And that was, kind of, a new potential for me. Being in Durango, I always had friends that mountain biked. So, I would train with them in the summer as cross-country skiing training. I then went to the University of Colorado, with a ski scholarship. While I was there, I tried a mountain bike race — because we would train on mountain bikes. In the summer, I was riding as much as the people that were racing mountain bikes. I watched a lot of mountain bike races here before I started racing. It would be live in-person or on TV, as there was pretty good coverage. There were a lot of professionals here in the early days of the sport, like Ned (Overend), who was a local hero. So, that idea that it was something you could actually make a living at, was kind of early seated in my mind.’

When did you do your first mountain bike race?

“I think I did my first race, the Iron Horse Mountain Bike Race, in ‘88. I was going to school in Boulder and ski racing. It was in the year I graduated from high school. The race went great, I was super fit I think at that point; it was [all] beginning, so I think I raced sport or expert — I think after a couple races I got upgraded to expert, in ‘89.

“I actually decided I was going to race quite a bit in expert category. I remember racing the Colorado Point series — which was a big deal at the time — then went to Nationals in Mammoth and won that, and that’s when Worlds were here in Durango (‘90) and I was living in Boulder at the time. I decided I was going to do the qualifying race, so did the pro race here and made it into the elite race for Worlds. Probably just through stupidity of not knowing, not questioning anything, I had a good race and was 10th in that Worlds so then I started asking myself the question like, alright is this the path forward? You know, as a sportsman. If that’s something you want to do – is it going to be skiing or is it mountain biking? I debated internally. They’re very complementary sports but, you know, at some point you’re going to have to specialise [in one] if you want to be competitive at the top level.”

When did you go pro?

‘91 was my first full-season pro, and I raced for Manitou. And that was before the Answer licensing relationship with Manitou. So, that was Doug Bradbury actually building bikes in Colorado Springs and me coming down from Boulder and seeing his shop. The way we got the budget to go racing was through the Japanese importer for the bikes. They were selling them for ten thousand dollars in Japan back then. You know, it was really high prestige. They were like, yeah, a professional racer will help us sell, will finance the race team. Doug called me up and he said, let’s go racing. And after that World’s performance, I had a few options. But, this was one that just resonated with me and I’m really grateful for that because Doug has one of the most natural design engineer sensibilities of anyone I’ve met in the (cycling) industry, and he let me participate in that process and that was kind of the beginning of understanding, you know, the technical aspect of building bikes and geometry. So, he built me a bike and said, ride it and let me know if you want to change anything. And, at that point, I had not studied bike geometry – I didn’t know anything from anything – but I rode it with his stock geometry.

I asked for a bike that was like two inches longer and he was like alright, I’ll build it for you if you want. But, back then, it was like way outside of the box. And again, that was just me not understanding what the standards were. It worked good. That was the bike I raced. There were other people probably realising small tweaks from road geometry to mountain bike geometry were not enough, so the wheelbase started getting pretty long and it was good when you’re really tired at the end of the race and you just needed the bike to go straight with stability.

Then what happened?

“It was the second year – ’92 – as a racer with Manitou; I kind of outgrew that program and so I had a lot of options for the ‘93 season and signed with a team that was a Volkswagen Schwinn, which ended up falling apart in the spring. I told my parents I wasn’t going to graduate school — I was going to race. I had no sponsor to start the race season.”

And was it just budget constraints?

“Well, the person who was putting that program together was not transparent as far as all the deals with co-sponsors had been signed. So, it was going to be a big team, and we were all left holding their dicks in our hands. The season opener at that point was Cactus Cup in Scottsdale, Arizona. I went there as a privateer on a Dean titanium because they were a local Boulder company. I’m like, I’m kind of hosed here, I just need a bike. They were really gracious in helping me out. And I went there and was sick, didn’t race that good. At this point, I’m like, maybe this is a really dumb idea. And I’m sure my parents were thinking that; it’s a dumb idea. It’s a really dumb idea. But I stuck with it and moved back here (Durango).

“I worked in a dental lab and rode — the dental lab made me enough money to get to races. At that point, you know, all races had some prize money. Like if you’re doing well, you could actually make some money and prize money to supplement a budget for a race season. Then Trek decided at that point that it was time for them to have a professional mountain bike team. And so they called Zap Espinoza at Mountain Bike Action. They called him first and said, we’re starting a mountain bike team, and we need riders — who’s left unsigned and who’s available? And he recommended me. Late in the spring (’93), they hired me, and I was the first mountain bike racer they hired. The first professional mountain bike racer the company had. So yeah, that was the beginning of my career at Trek.”

Sheesh, tell me about your pro career from there…

“It was great! I went World Cup racing and got to see the world and got to live my life to its potential as a professional cyclist, but wanted to reach the pinnacle of the Olympics. So, pursuing the U.S. National Championship and trying to get on an Olympic team was a big driving force for me. And, you know, when I switched from skiing to mountain biking it looked like the Olympic part, and being an Olympian, was not going to be part of the picture because mountain biking was not at the Olympics. Then, in ’96, mountain biking got into the Olympics.

“The qualifications for the Atlanta (Olympic) team were held in ’96; it was six races, three in the in the ‘95 season, three in the ‘96 season. I was probably not a favourite to make the only two spots for the team, but I kind of made a level up jump that year and started getting good points in that points chase. By the sixth race, I think Tinker had already qualified. He had an automatic qualification, maybe from a World Cup win. Then, from everyone who was left, I was leading in the points — so that was amongst myself, a teammate, and a few other people that were in the mix — and I was leading going into that sixth race. Then, the day before that sixth race, I’m on really good form, practicing an A and B line, trying to do the A line as fast as possible, squeezing seconds out of the technical feature — and I crashed and broke my collarbone. So that dream was kind of crushed at that point.

“The highlight was that I took the time off and then came back. You kind of revaluate your choices at that point with the let-down, but I decided it was worth continuing to pursue racing and that lifestyle. So, I came back — I think with a new drive — and I won my first big National race in a really close battle with (John) Tomac in Park City, Utah at the end of that ‘96 season. Then in ‘97, ’98 and ‘99 I started winning a lot of races in the US. A similar Olympic qualification process was in place. During the first World Cup, in the spring of 2000, I broke my leg. So that seemed like, all right, this is just happening all over again. Another revaluation of all your choices. I concluded that if I don’t make it, that’s fine; that’s just what’s in the cards. But, if I don’t completely dedicate myself to the recovery, I’ll regret it. So, I was disciplined in my recovery and pushed the boundaries of what the doctors said I should do and came back and was able to hit the last two Canadian World Cups and get more points than the rest of the people — and just squeaked in on that Olympic team.

“So, I got to have the Olympic Games experience that year. In the same year, I’d won the National Championship after many seconds and thirds. I’d kind of checked all those boxes at that point. You know, there was a lot of satisfaction from that and from going through that process, especially being with one company (Trek) long-term and being into the product, into things and asking all the questions like, well, if we change this how would it give me an advantage? I was always asking the engineers about possible opportunities.”

So, that’s how you ended up working for Trek?

“As a racer, I would try stuff that other racers weren’t willing to try because of the risk. And I learned a lot through that process, and I developed a lot of relationships with the engineers and product managers. As my racing career was winding down, I made it clear that I wanted to move into a product development role and focus full-time on that and they (Trek) very graciously gave me the opportunity to do that.”

How did your role with them develop?

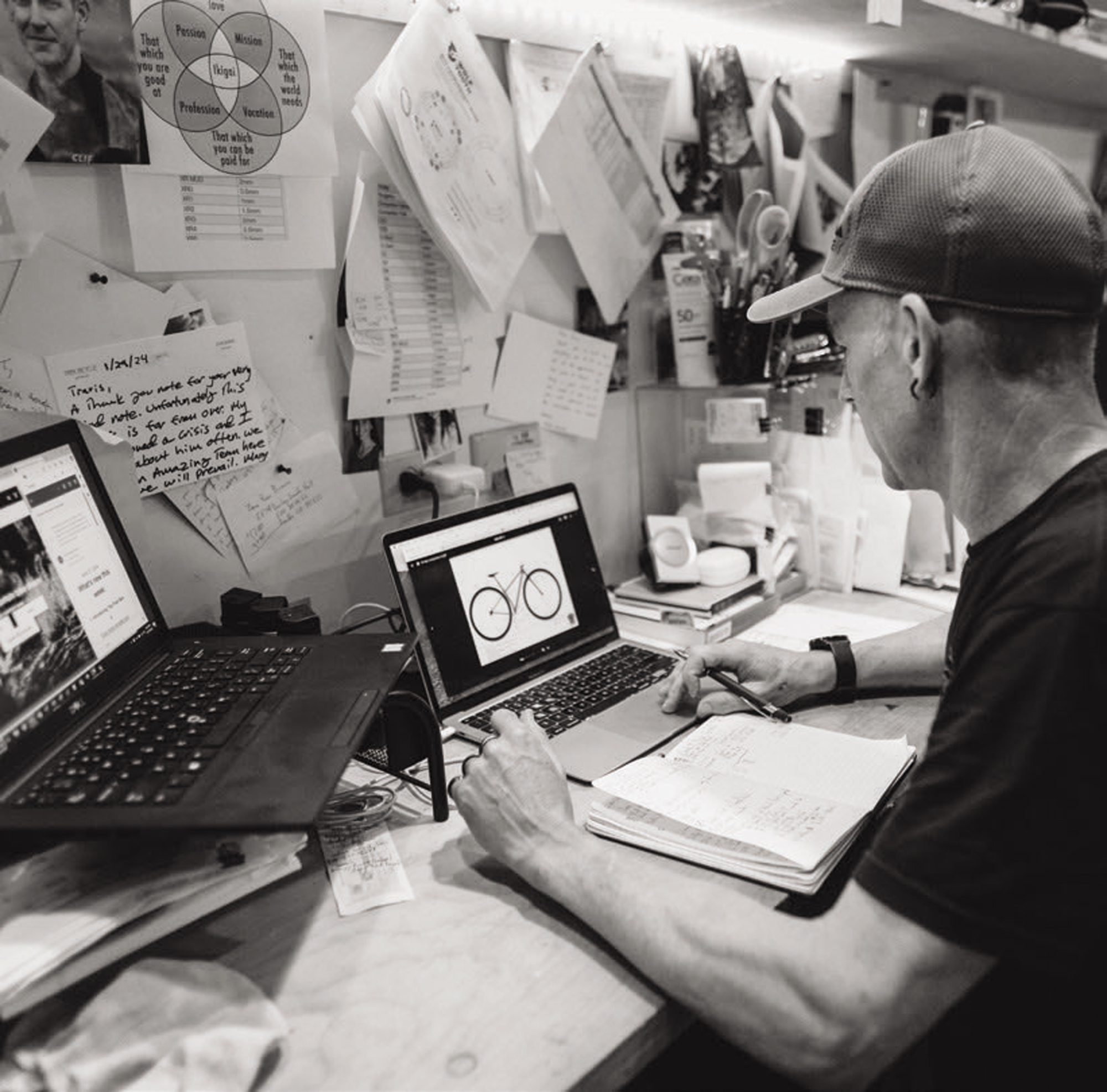

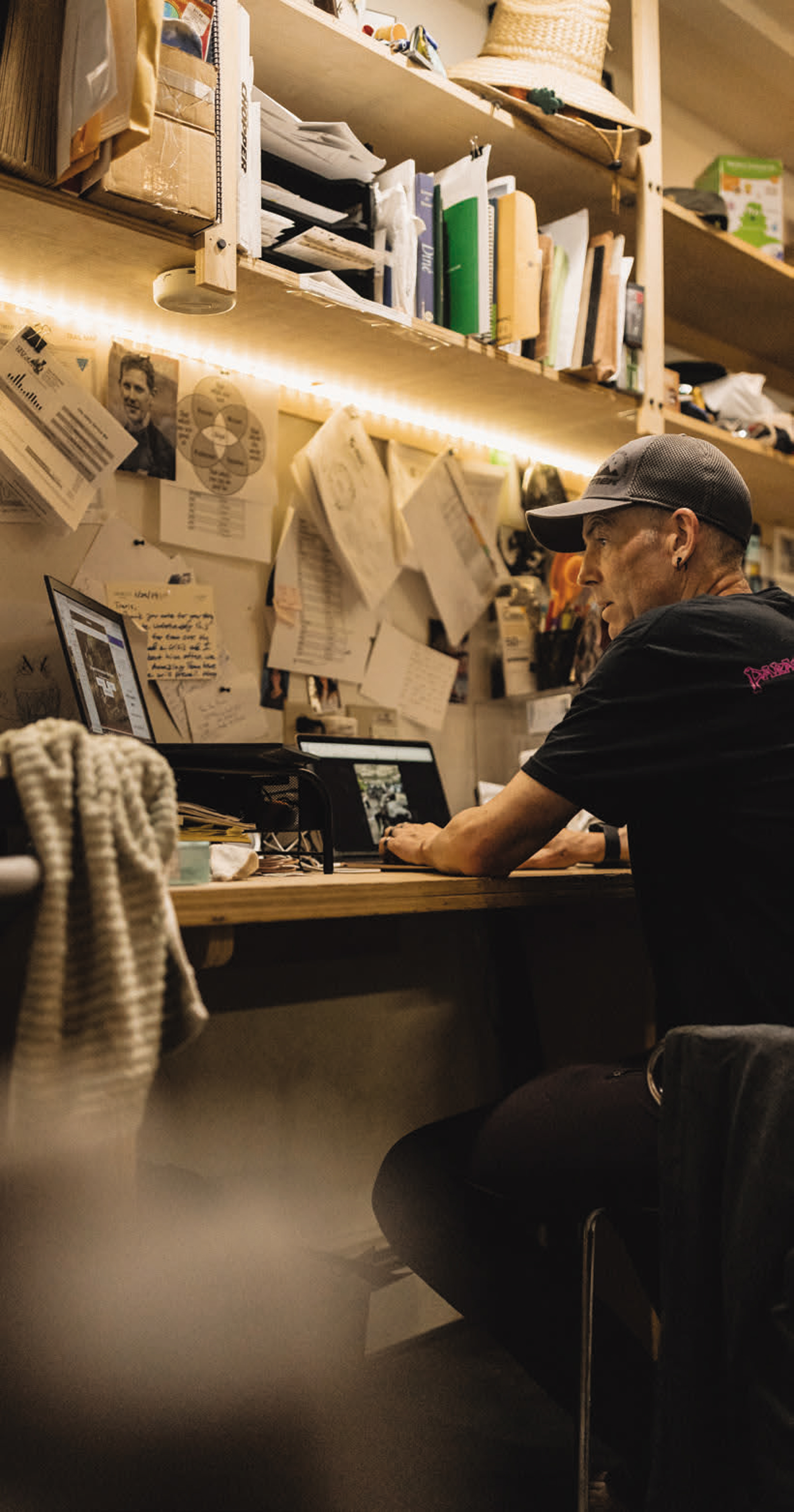

“I was focused on the development role as a rider and I was racing a lot still, so it was pretty clear that we needed more than just me out there focusing on testing — so I started building a group of field testers around me to help me figure stuff out. People with different skills, people that could ride different products. Now we have basically a West Coast (USA) group and East Coast (USA) group and the Colorado group — and a group in the Netherlands too. We’ve kind of reproduced what we built here in Colorado in a bunch of other places, globally. We’ll (Trek) continue to do that as we have the resources to do it, because it’s proven to work. You learn a lot and you’re exposed to nuance and opportunity through all those hours of pedalling that you can’t get any other way.

That same application, like training in the field, just married up for me and for my interests and curiosities – it was a complete natural dovetail. It was pretty easy to go from a professional racing lifestyle to a different occupation because I still got to ride a lot, and I still do that now, right?

You still have the passion to ride?

“Yeah, [my enthusiasm] for pedalling has never waned or lost interest, and I have always stayed hyper passionate about the sport. Of course, there are days you don’t want to ride but I have found aspects of mountain bike riding that are really medicinal for me and help make me a better, healthier person. So to continue to be able to do that as part of an occupation is really a blessing. It’s been a great lifestyle for me, and it’s been a great working relationship with a good company — you know, the people at Trek are some of my closest friends and they kind of have a no asshole policy.”

What does the future hold for the sport and yourself?

“Well, its broad. Cycling has all these different nuanced applications, especially the soft surface disciplines that are still evolving at a fast pace. The most recent example is gravel. When I first started mountain bike racing, we all did cyclocross and mountain biking on the same bike. You know, if you look at that bookend to where things are now, that evolution of the sport is pretty profound. The endurance side of things has a whole suite of disciplines. The gravity end of things has a whole suite of disciplines. And so the trajectory of evolution is really still pretty steep. I think that makes the industry really exciting. And it’s still going to continue to grow. Obviously, we have plateaus, and stuff that’s been done and is refined and [made more] sophisticated.”

Do you think that diversification and segmentation will continue within mountain bikes? And then obviously we’re not even touching on eBikes in that sense, right?

“Yeah, that’s an evolution that very few of us would have predicted — and it exploded in a very short period. If you look at that disruption to the bike industry, it’s really like the disruptions that mountain bikes provided the industry in the late 80’s and early 90’s. You know, a huge growth boost that brought lots of new ideas and concepts and technologies and profit opportunities and stability to grow the industry. I think there’s a lot of things about eBikes that are cool. Like the equaliser part — the fact I was able to do a ride with my dad, when he was like 75 years old, you know. And we would have never been able to do that together, if it wasn’t for eBikes. And rides with my daughter and rides with my wife — eBikes allow a different shared experience. [Then there’s] the utility part — where people are getting out of their cars and onto bikes, which is amazing.

It’s about attracting new people to the sport because, honestly, mountain biking is hard — like, really hard. And that was a big hurdle to entry for a lot of people. But eBikes have eliminated that to some degree. It brings new people into the sport. And that’s good for everybody. I understand what an active lifestyle does for quality of life, and I think eBikes are providing that opportunity for people that wouldn’t have seen it otherwise.’

What does the future look like for Travis?

“I ride bikes dictated by the product pipeline, so that’s not total freedom or riding as a pure part of your life… but it does mean that it’s an imperative part of your daily occupation. So, there’s two sides. At some point, I’ll retire, and will be able to ride any bike I want on any trail I want, and I’ll love that — but it’s pretty good right now, too. I can’t complain — I mean, honestly, my whole career (which is kind of avoiding what most people would consider ‘real jobs’) has provided a stability — financial stability — for myself and for my family, which is kind of perfect. It’s kind of a dream to be able to do it that way. So, nothing’s perfect. There are light and dark sides to every part of it, and I will enjoy the freedom of not having that at some point. I’m not counting days until retirement.’

What does cycling mean to you?

“I think what I said before; it’s a really medicinal component of my life in a lot of dimensions. So, it’s an occupation, provides me a livelihood. The physical activity and competition now, I have an appreciation for that component of the human experience that I probably didn’t appreciate when I was racing full-time. Bikes are magical machines which you can ride as far as you like, and it can be accomplished under just human power.”

Lastly, your take on Aotearoa?

“I did a month trip down there after that Single Speed Worlds. There’s a lot of places I’ve travelled to that I’ve enjoyed, but very few places I’ve been to where I thought, ‘I could live here’. For me, New Zealand was like that. I described it like it has everything in Colorado — plus an ocean. It’s your connection to the outdoors and to nature that is important — you get a lot of that outdoor experience. I am scheming up a way to return for a bikepacking trip. New Zealand’s pretty bitchin.”