Cannondale Habit LT1

Words Lester Perry

Images Henry Jaine

RRP $8699

Distributor Worralls

A summertime fling.

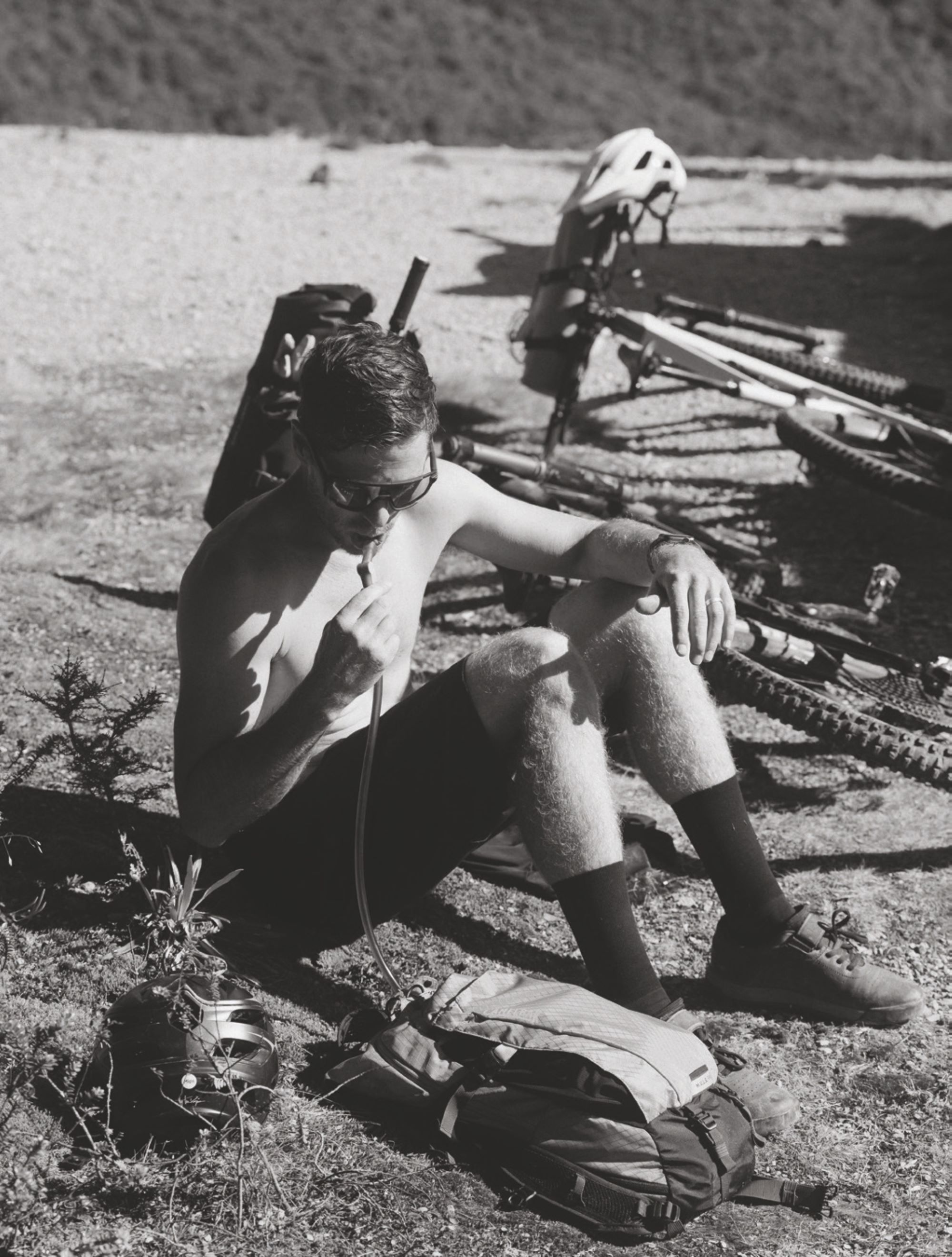

I was sitting at the top of St Arnaud’s ‘What’s Up Doc’ climb; my watch showed 7:30am. It took me an hour and a bit to get here from where I’d camped, and the sun had just peeped over the ranges beside me. Alone aside from the bike, I pondered how many days we still had together, knowing our time together was soon to end.

It wasn’t love at first sight, and although she had some flaws, I’d learned to live with them. Eventually, when the curtains closed on our time together it was tough; this diamond in the rough had left a mark and I didn’t want to part with it.

I was stoked when Cannondale hired a host of creative and stylish riders to form the Waves team, including the unmistakable ’Rat Boy’ Josh Bryceland, to rep their Habit platform. At the time, a short travel trail bike leaning towards a playful style of trail riding. I wasn’t sold on its relatively short travel though; its 130mm in the rear and 140mm front travel left me wanting more. It was just too limiting for my preferred riding spots.

Step forward a few years and in comes the Cannondale Habit LT 1, a longer-legged version of the Habit. The new LT (Long Travel) platform followed on from the Habit, taking its rugged good looks, balanced geometry and all-around fun factor, but in a slightly more forgiving 140mm/150mm package – right up my alley. The LT’s longer travel broadened the type of riding it’s suited to, pushing it toward the rowdier end of the spectrum but without the excess weight and sloth of a full gas enduro bike.

Having spent the bulk of my recent summer months aboard the Habit LT 1, both on my local trails and across a full buffet of South Island holiday road trip adventures, I’ve put this rig well and truly to the test, discovered what I liked and disliked, and ultimately got a good appreciation for what it’s all about.

Before I even set eyes on the bike, I needed to let Cannondale NZ know what size I’d need. According to the Cannondale size chart, at 176cm tall I sit right at the top of the Medium, or bottom of the Large size. What to do? Comparing the geometry of the Medium to that of my own ride I decided it was too short, and the Large was probably larger than ideal, sort of a Goldilocks’ porridge situation. I came to the decision that I’d likely feel cramped on the Medium but could get accustomed to the Large and its 475mm reach. A few weeks later the rig arrived fully built and ready to roll. The Large did feel ‘large’, but not too big; game on!

Clean lines and oversized junctions set the scene for the Habit LT1’s frame. Visually, there’s nothing too out of the box or polarising, although the headtube junction and bottom bracket cluster are pretty substantial. I wouldn’t go so far as to say they’re overbuilt, but those junctions are a noticeable feature of the front end. A full carbon construction, everything other than the suspension linkage is sweet, sweet, carbon fibre, including the chain and seat stays. With no seat stay bridge to be seen, the seat stays are separate, tied together only by the yolk that drives the shock, and the rear wheel axle.

With its comfortable geometry, it’s a bike that you can easily manoeuvre around, or jump over whatever’s in front of you - think a paring knife as opposed to a meat cleaver; they both get a similar result but get there in distinctly different ways.

Cannondale has a somewhat chequered past in some respects, due to regularly adding proprietary technology or features on their bikes, which has ultimately put some riders off making the step onto the brand. It’s great to see nothing too out of the ordinary on the Habit LT line, just industry-standard sort of stuff. A threaded bottom bracket, 148 boost spaced rear end, and regular tub-in-tube internal routing for cables, no niggly headset routing or strange rear wheel offsets on this bike!

Five frame sizes are available, all with 29” wheels, aside from the XS with 27.5” wheels. It’s great to see some size-specific chain stay lengths across the sizes. Small and Medium share the same chain stay length, all other sizes are unique in length. Different length rear ends also mean size-specific rear shock and suspension kinematic tunes, keeping the bike optimised for the rider, however tall they maybe.

The head-angle sits at a conservative but precise 64.7° and the seat tube is an acceptably steep 77.1°(effective). Geometry that’s neither here nor there, but current, and nails the use case for the bike. The main frame has a single bottle cage mount on the downtube, and an accessory mount under the top tube. In the large frame I tested there was heaps of room for a full-size bottle in the front triangle – that’s a win in my book.

Cannondale designers have done a nice job of helping to keep the frame looking fresh long-term, and quiet to ride with well-thought-out rubber protection on the downtube, chain stay and seat stay. Strategically placed top tape keeps other key areas on the frame scuff-free. The addition of a rubber mudguard behind the bottom bracket, over the main pivot, keeps the area contaminant-free and helps with bearing longevity.

Spec-wise, we’re looking at some familiar, tried-and-true hardware on the Habit. A complete SRAM GX Groupset, there’s only one cable and it’s not an electronic one, a complete manual setup here. If you want to upgrade to the latest T-type transmission, there’s a UDH hanger on the frame to allow for that. The GX groupset in this most recent iteration has been around a few years now and it’s a workhorse on a lot of bikes of this level. No complaints here, it just needs the occasional tweak of cable tension, and a clean chain to maintain hassle-free performance.

SRAM’s Code R brakes, with a 203mm rotor up front and a 180mm out back, offer just enough power for this rig. I don’t think I’d manage with anything less on this bike. There’s plenty of adjustment on offer, so even the pickiest of fingers can find the perfect lever position. They’ve got a decent, solid feel at the lever and only on the longest descents I found a little fade in the rear, no doubt exacerbated by my rear-biased braking and that 180mm rotor, a 203 rotor on the back would be ideal.

The bike has a stable, planted feel on the trail, but still feels that there’s enough support to keep it playful and responsive rather than subdued and dull, allowing you to boost from trail features and not feel like you’re blowing through all the travel on landing.

The cockpit and dropper post are taken care of by Cannondale in-house labels, while the grips and saddle are Fabric branded items. The dropper is 170mm and is nice and smooth – not a shotgun fast return but not so slow as to be an issue. The post doesn’t have the lowest stack height, but the length worked ok for me, although with a lower stack post, I’d comfortably go up to around a 190mm drop. Considering I’m right at the bottom of the height recommendation for the Large, I’d imagine the 170mm post won’t be ideal for those more towards the centre or top of the height chart. The seat tube on the Habit LT isn’t the shortest at 445mm, limiting the maximum drop possible on the bike. The dropper lever does its thing with no qualms, and is nice and smooth with a light action.

The HollowGram carbon bar is huge for a trail bike with a 30mm rise, and a full 780mm width – that’s a lot of height for a trail bike, especially one with such a large stack. Riders on the taller end of the spectrum will appreciate this much height, but as you’ll see further on, it was a slight niggle for me. The stem is also a Cannondale in-house number and comes in a nice new-school 40mm length.

The WTB KOM i30 TCS 32-hole wheels on proven DT Swiss 350 hubs have been trouble-free as expected. Not once have I had to pull out the spoke key to remedy a wobble after a cased gap or smashed root. There’s no need to discuss the hubs as it’s fair to say these beauties would see a tonne more riding before I’d even need to look at any bearings. A clean and lube of the freehub may have been necessary, had I been riding in the wet regularly – but over the review period, I touched the mud just a few times.

Shod with a pair of Maxxis tyres, there are no surprises here, or sidesteps needed from the stock spec: a Minion DHF 29×2.5” takes care of tracking up front, while highspeed rolling, but is sketchy in some conditions, with Dissector 29×2.5” features on the rear. It’s good to see Cannondale have the foresight to spec the EXO+ casing version of the tyres, no need for immediate off-the-floor upgrades if you’re an aggressive rider or live in a rocky area where you’ll appreciate the sturdier EXO+ casing over the often specced EXO. The Dissector is an acceptable summer option as a rear tyre, and great in conditions where it can cut in for some traction, but in loose or muddy surfaces it struggles for braking traction (the central knobs are quite low). The side knobs appear to lack support and fold over on the hardpack; great for squaring off berms or flicking a Scandi’ into a turn, but not so much for overall control – wear it out and replace it with a Minion DHR2, problem solved… although a little slower rolling.

Hanging off the front of the chassis is the supple and controlled (thanks to the new Charger 3 TC damper) ROCK SHOX Lyric Select + fork. I’ve been impressed by how good the fork is in all circumstances; high-speed chatter, no matter; big- hitting bangers, no biggie. A bit of experimenting with the high and low-speed compressions left me with the high-speed wide open and two clicks from fully open on the low speed; this seemed a decent setup for most conditions of trails I ride.

The rear end is damped with a ROCK SHOX Super Deluxe Select +. A visit to the ROCKSHOX TrailHead website for some baseline setup advice left me at a few hairs under 30% sag. I subtracted a couple of clicks from recommended on the rebound, speeding the back end up to just how I like it.

For sure I prefer the Habit LT’s active, supple suspension over a higher-anti squat and consequently more ‘locked out’ pedalling experience, particularly at this mid-travel level.

Once the suspension was dialled in, I took the bike for a quick ride and my first impression was that this bike is built for fun: poppy and playful. My second impression is how high the front end is. The large 644mm stack combined with the 30mm rise of the 800mm wide HollowGram SAVE handlebar made it super easy to chuck a sweet wheelie, or manual through a section, but on everything other than steep descents left me feeling disconnected from the front tyre. After some time with my trusty tape-measure, I landed on a 760mm wide, 15mm rise bar and a single 10mm spacer under the stem. Lowering the front made me feel more centred on the bike, with more weight over the front but still keeping the front end high enough for some aggressive riding. Once I got the front end to an acceptable level (for me), it unlocked the cornering of the bike and I felt comfy and at home. Swapping handlebars from new may be needed by some riders, but as bar height and width are certainly a personal preference it likely won’t be necessary for everyone, particularly if you’re on the taller side.

The rear suspension kinematic is linear through most of the travel, feeling consistent through most of the shock stroke and finishing with a steep ramp-up at the end of the travel, preventing harsh bottom-outs. The bike has a stable, planted feel on the trail, but still feels that there’s enough support to keep it playful and responsive rather than subdued and dull, allowing you to boost from trail features and not feel like you’re blowing through all the travel on landing.

Descending on the Habit LT is just plain fun. This isn’t a huge travel rig you can plough un- controlled into chunky rough sections, relying on huge travel and slack geometry to keep you out of trouble. With its comfortable geometry, it’s a bike that you can easily manoeuvre around, or jump over whatever’s in front of you though – think a paring knife as opposed to a meat cleaver; they both get a similar result but get there in distinctly different ways. Central rider weight keeps the bike planted, aiding traction and helping keep you very much under control. Multiple times I exited a trail surprised at how the bike handled some of the rowdier sections, particularly as it hasn’t got the longest travel, or most progressive geometry. On steep trails, with lots of large successive hits, the suspension stiffens up somewhat under the braking forces, causing the back end to feel quite harsh. Not a deal breaker, but more noticeable than some other bikes in this travel range and we’re not really riding that type of terrain often.

Low anti-squat means the rear suspension is still plenty active under pedalling, ideal for a bike aimed at descending fun, rather than pedalling prowess. Of course, this means it’s obviously very active on steep climbs, sagging into its travel and creating bob. I found this quite noticeable and was surprised by just how much it could sink into its travel on really steep uphill pitches. Fear not though; the lockout lever is within easy reach and very effective. I found most of the time I’d throw the lockout on for any extended, consistent climb but leave it open for anything resembling a technical climb as the extra traction it allowed was welcome. For sure I prefer the Habit LT’s active, supple suspension over a higher-anti squat and consequently more ‘locked out’ pedalling experience, particularly at this mid-travel level.

The bike tracks well across off-camber and through flat turns, partly due to the geometry putting rider weight centrally between the wheels, partly due to the supple suspension kinematic, but also because of the back end having a healthy amount of torsional compliance, aka flex. In recent years, designers have been moving away from the aim of having the stiffest bike, aiming for a perfectly tuned flex through the frame. If done effectively, a back end with more flex can also mean better tracking, assisting with overall rider confidence, and feel; I reckon the Habit LT nails this, whether that was the design team’s intention or not. This compliance means the Habit LT isn’t the spriteliest bike while sprinting, but it isn’t a cross-country bike either, so pedalling is secondary to overall roost-ability and fun.

Mellow trails (i.e. most of what we ride) are a blast on this bike; it picks up speed quickly, and jumping into sniper landings or pumping through sections gives a noticeable speed increase.

Cannondale reckons the ‘LT’ moniker stands for Long Travel, but I wonder if it really stands for, as the youth of today say: “Lit Time” (i.e. a “great time” to those of us who are slightly less youthful). Out of the box, as you’ve seen, there were a few things I wasn’t a fan of and, although they’re all personal preferences, they meant I needed to spend precious time getting to my optimal setup, this isn’t exactly a ‘get on and go’ bike. That said, once I got my setup dialled, this bike was awesome. It’s really changed my perspective on what bike I need as my ‘everyday ride’ and, with modern suspension, geometry and frame design, a shorter-travel bike like this can now be on par (or better) than a longer- legged bike from only a few years ago and make for an overall better experience, regardless of the few scenarios it’s not in its element.

Toby + Rory Meek: Redefining past conventions

Words & Images Riley McLay

New Zealand has always punched well above its weight when it comes to producing high performing downhill racers on the international circuit. New Zealand racers have always been synonymous with a DIY mentality and lifestyle-based approach, largely popularized by the VANZACS.

However, with the sport moving rapidly to a more professional outlook, the qualities that set New Zealand riders apart in the past may not be so fitting in today’s racing climate. Even with some of the most recognisable and world renowned tracks for training and progression, the Kiwi racing scene faces the conundrum of a steady decline in the number of junior riders making their way through to competing at elite level. This could be due to a change to the unpopular format UCI has adopted, or the broader financial pressures faced by race teams and support systems in and around the races. Not to mention the agonizingly close times being laid down by some of the top riders. Amidst these challenges, one Queenstown-based family is on a mission to redefine past conventions and bring a high performance framework to their racing on and off the bike.

TOBY AND RORY’S RACING HAS TAKEN THEM ALL OVER THE WORLD. FROM A YOUNG AGE, THEY HAVE CHASED BOTH BMX AND MOUNTAIN BIKE RACES ACROSS EUROPE, NORTH AMERICA, OCEANIA, ASIA AND SOUTH AMERICA, ACCUMULATING A COLLECTION OF NOTEWORTHY RESULTS.

The Meek family have always had the mindset that success and innovations tend to grow from humble beginnings. Originally Dunedin based, Kiwis Steve and Donna packed up their lives and moved to Hong Kong in 2003. As a young couple, they sought the adventure and experience of working life as expats. Both avid mountain bikers, they were able to take advantage of the plethora of tropical jungle trails that Hong Kong offers. It wasn’t long before their two sons, Toby and Rory, had arrived and were introduced to a life of riding bikes. The boys would quickly make the jungle their own. As a family, they would constantly add to the network of trails around them, building their own tracks for the boys to hone their skills. The boys adapted to a racer’s mindset, both forming their pedigree from BMX racing – in which they have represented New Zealand at a world championship level, multiple times. The boys bounced between racing BMX and mountain bikes and as their skill levels progressed, Steve became frustrated with the limited options available for bikes for the boys to ride. With most bikes at the time weighing a tonne, they were not suited for younger riders. Steve made it his mission to create a solution so that the boys weren’t being held back and could further progress their skills. It started off with adapting one of Toby’s BMX bikes with a 100mm travel fork, from a 26 inch mountain bike. This created a bike that was far lighter than the mass market kids bikes, and the forks gave Toby more of a fighting chance for riding control when it came to getting down steeper trails. Being a hardtail came with some limitations, but it allowed Toby to go out riding with Steve. Soon enough, Rory also needed a boke, and with Toby outgrowing the capabilities of the hardtrail, Steve took it upon himself to come up with something bolder. Steve went out and sourced a size small Giant Trance and chopped it down to create a custom full-suspension bike for Toby. Resizing an adult frame to accommodate a child isn’t as simple as it sounds. Steve had to formulate the best possible design for shrinking the frame to allow enough stand over height for Toby to fit the bike and be as comfortable as possible. With his firsthand experience and seeing an obvious gap in the market, Steve formed MeekBoyz, a bike company whose goal is to provide the world’s best high performance downhill bikes for children. The MeekBoyz design criteria centred around the bike performance, weight, tailored geometry and, most importantly, a full-functioning suspension system for young riders with capabilities to ride down more advanced trails. Having a composites background, Steve chose carbon fibre for the bike frames and rims. It was a no-brainer as it is light, more versatile than other metals and has long-term durability. Working with carbon is a highly labor intensive task and requires a large work space. Fortunately, being based in Hong Kong enabled Steve to access and set up in the epicenter of the carbon bike industry, in Taiwan and China. Steve is adamant about only putting the best components on his bikes. From years of experience, he knows only top quality parts ensure the integrity of a high-performance bike range. This attention to detail eliminates any unneccessary stress of worrying about equipment and lets the boys focus on the racing.

Toby and Rory’s racing has taken them all over the world. From a young age, they have chased both BMX and mountain bike races across Europe, North America, Oceania, Asia and South America, accumulating a collection of noteworthy results. Rory achieved third in the world – twice! – for his age group in BMX racing and Toby raced at a world championship level for five years. They are no strangers to the UCI world cup circuit either, as they frequented as spectators, and competed in events such as Crankworx Whistler and US Open – where Rory has won his age group twice. The boys were even invited to a surreal experience to race the Longling DH Memorial Event, in Yunnan Province, China, where they competed against other racing phenoms, including Jackson Goldstone. When the boys reached high school age, the family moved back to New Zealand and settled in Queenstown, in search of a more balanced lifestyle and a better base to focus on racing. The family is very passionate about biking not being the be-all and end-all, and feel having a well-rounded worldview is imperative to personal growth. With the pool of talented riders across New Zealand, it can be hard to stay grounded and focus on what is important, but life skills learnt away from the bike carry over and greatly improve results. This is why the boys were always encouraged to chase other hobbies like hunting, fishing, surfing and even kite surfing – which they also excelled in and competed in at a high level. The family model their operations off the Atherton family and admire the success they have, while keeping things tight-knit.

WITH MOST BIKES AT THE TIME WEIGHING A TONNE, THEY WERE NOT SUITED FOR YOUNGER RIDERS. STEVE MADE IT HIS MISSION TO CREATE A SOLUTION SO THAT THE BOYS WEREN’T BEING HELD BACK AND COULD FURTHER PROGRESS THEIR SKILLS.

Standing out on results alone doesn’t always mean you receive the support you need to race at a high level. In the early days, it was hard to stand out and the family found it challenging to find sponsors to support the boys. The family was early to implement the use of social media to promote the Meekboyz brand, and it has been a pivotal part of their success. What started off as the boys filming and sharing videos of their riding online, has snowballed into picking up notable long-term sponsors, like Continental tyres, and accumulating over 35,000 Instagram followers. Social media also benefits the Meekboyz physical business of selling bikes, which then allows more funding to flow back into supporting the boys with their racing. This extra exposure resulted in Toby joining Markus Stöckl’s MS Mondraker race team in 2020. Markus Stoeckl, team owner (and mountain bike world record holder) invited Toby to travel with the team through Europe and learn the ins and outs of how a professional race team operates. Team rider, Laurie Greenland, was instrumental in showing Toby the pace required to race at world cup level and served as a great role model. Toby then went on to sign onto MS Mondraker Team for his remaining two junior years. He was over the moon to join the team and ride alongside someone as successful as Laurie, who he had always looked up to.

In Toby’s first elite junior season, he suffered two major injuries which cut short his racing. Firstly, a cracked pelvis training in Leogang, Austria, followed by a broken arm in Lenzerheide, Switzerland. In Toby’s second year, he came out of the gate with a great result, 6th in his first world cup race in Lourdes, France. He then suffered a dislocated shoulder in the following race, in Maribor, Slovenia, which forced him to come home to New Zealand to have shoulder surgery and miss the rest of the season. Due to his injuries, Toby felt like he had unfinished business and had not achieved the results he knew he was capable of. In 2023, Toby signed on for another year with MS Racing and bounced back to have an impressive New Zealand season. For his first year, competing in the elite category, he won every national round that he entered. This span of good form continued as he went on to win the New Zealand national downhill champs, donning the coveted New Zealand sleeve for the 2023 international race season. Rory’s results were equally impressive, finishing second in the downhill national round and Crankworx summer series events, hosted in Cardrona. He also collected a third place in the under 17 category at the downhill national champs event hosted by Coronet Peak to top off the season, creating a great platform to work from moving into the elite junior category.

IN THE EARLY DAYS, IT WAS HARD TO STAND OUT AND THE FAMILY FOUND IT CHALLENGING TO FIND SPONSORS TO SUPPORT THE BOYS. THE FAMILY WAS EARLY TO IMPLEMENT THE USE OF SOCIAL MEDIA TO PROMOTE THE MEEKBOYZ BRAND, AND IT HAS BEEN A PIVOTAL PART OF THEIR SUCCESS.

Toby’s UCI world cup season started off extremely positively, making it through to the finals and finishing 27th at the second round in Leogang, Austria. He backed this up by achieving four more top 60 results and was an agonizing two hundredths of a second off qualifying for the finals event at Pal Arinsal, in Andorra. During the season, the team was going through big changes, while a majority of the team’s riders were battling their own injuries. Fortunately, Toby remained injury free. He had hoped to test the upcoming Mondraker DH prototype being developed by the team for the world cup races, but unfortunately this opportunity never eventuated. This was a disappointment for him. One of the challenges of being the youngest rider is the limited access to the same parts and opportunities as more experienced riders. This is likely to change, given the next generation of riders competing at a world cup level now are proving that they are just as fast and talented as the seasoned riders on the circuit. Despite these shortcomings, Toby was still able to finish the UCI season in 60th place overall, and has set himself a strong foundation for more success in the future.

Although the mountain bike industry and current racing climate face turmoil, the Meek family have decided to launch their own UCI race team for the 2024 season, under the name ‘MeekBoyz Racing’. It will be Queenstown’s first homegrown factory UCI team and will be the first time both Toby and Rory have been on the same team since they were young. This will also be Rory’s first UCI season in the junior category. Creating Meekboyz Racing will allow the family full control over the racing operations. This means they’re able to choose the best components and partner with brands to ensure the boys can achieve the best results possible, while keeping their family unit tight-knit and continuing their under-the-radar approach. The team is definitely one to keep your eye on in 2024.

CREATING MEEKBOYZ RACING WILL ALLOW THE FAMILY FULL CONTROL OVER THE RACING OPERATIONS. THIS MEANS THEY’RE ABLE TO CHOOSE THE BEST COMPONENTS AND PARTNER WITH BRANDS TO ENSURE THE BOYS CAN ACHIEVE THE BEST RESULTS POSSIBLE, WHILE KEEPING THEIR FAMILY UNIT TIGHT-KNIT AND CONTINUING THEIR UNDER-THE-RADAR APPROACH.

KTM Macina Prowler Prestige & Exonic eMTB

Words Lester Perry

Images Bevan Cowan

RRP $23,499 – KTM Macina Prowler Exonic | $17,499 – KTM Macina Prowler Prestige

Distributor Electric Bikes NZ

Although the familiar orange logo is shared between the moto and bicycle brands, since 1991 they’ve been two completely separate entities after the company was split into four individual companies: motorcycles; engines; bicycles; and radiators, leaving the bicycle company standing on its own two feet under new ownership. Nowadays, the brand has a comprehensive range, from high-end eBikes to Tour de France road racing bikes and even kid’s offerings. Unfortunately, only selected models are available here in NZ.

Having seen KTM eBikes on international websites and under a few E-Enduro World Cup riders over recent years, when the opportunity came up to throw a leg over one I jumped at the chance. Then the opportunity to ride one bike turned into the opportunity to ride two levels of the same platform, a real back-to-back comparison to see the difference between two similar bikes with a $6000 price differential.

We put two bikes to the test, the Macina Prowler Prestige ($17,499RRP) and the Macina Prowler Exonic ($23,499RRP). The bikes share a premium price tag (granted, there’s a chasm between the two values), and both share the same frame, handlebars, stem and tyres, but everything else is distinctly different.

First off, both bikes are stunning to look at. There’s a nod to their moto roots with long travel suspension (170mm rear; 180mm front) chunky tyres, mullet wheel setup (29” front; 27.5” rear), and, of course, their Bosch drive units. Paint schemes are distinct: the Prestige in its platinum bronze matte, and the Exonic in a translucent orange and black. Both bikes look slick, but the Exonic takes the cake in the right light, layers of carbon are visible through the paint and the sunshine really makes it pop!

Frame

Featuring a carbon front end, the lines are clean and lead the eyes back to the aluminium 650b/27.5” specific back end. There are bosses and space for a bottle in the front triangle – great! The frame features headset-routed cables and, being an eBike, there are a few tucked in there.

It’s a nice change to have the cables tucked out of sight instead of the commonly seen bird’s nest of cables some eBikes have. Headset routing of cables is a pretty polarising topic, although with so much going on with the bike in terms of cables, controllers, drive units, battery etc, this is not a cause for concern in my book as there’s lots going on elsewhere on the bikes, too.

The battery can be removed through the hatch along the top side of the downtube. It’s a slick operation, but if there’s a bottle cage mounted it could be fiddly as space will be limited to manoeuvre the hatch lid off.

Both bikes look slick, but the Exonic takes the cake in the right light, layers of carbon are visible through the paint and the sunshine really makes it pop!

Drive Units

Bosch has cemented itself as one of the top-performing drive units for the eMTB segment, and both our test bikes feature top-level units from the German powerhouse. The Prestige features the tried-and-true Performance CX Gen 4 motor, delivering 85nM of torque through its assistance levels; Eco, Tour+, eMTB and Turbo modes. Maximum assistance is 340% in Turbo mode.

Exonic-level bikes get the CX’s newer, more brutish sibling – the Performance CX Race – it’s about 150 grams lighter than its little brother and can deliver its power faster for less effort, getting you up to speed just a fraction quicker. It can crank out 600 Watts peak power – the same as CX but with up to 400% maximum assistance – in its Race mode. The Race motor shares the same lower three assistance modes as the CX, but trades Turbo for the full gas Race mode. The CX-level motor is great for a bike like this, but the Race motor is both figuratively and literally next level. I found I had to be on my toes when riding in Race mode; if I wasn’t taking notice or weighting the bike quite right, particularly while tackling a steep pinch, the power could easily spit me off the bike. The Bosch Flow app allows some customisation for how the power is delivered across assistance levels, and given some more time I might have tweaked the setup to not be quite so peppy.

It’s great to see the drive units specced with 160mm length cranks, anything longer on an eMtb is too long in my book! Prestige bikes get solid-looking alloy KTM E-TRAIL cranks, and Exonic bikes step up a notch to a swanky FSA CK-702/IS Carbon crankset – very nice indeed. Out on the trail, there’s no discernible difference, but I’d imagine the carbon cranks of the Exonic would be marginally lighter.

An often-overlooked feature both motors share is the Extended Boost. When in eMTB or Race mode (where applicable), the motor continues to run on slightly after coming off the pedal power, continuing to deliver drive for a split second longer. This helps keep a consistent delivery of power, regardless of how bad your pedal stroke is, or having to stop pedalling to get through a technical section – think, a quick pause or half pedal kick while climbing a technical section to avoid clipping a pedal. The CX motor has the same feature, but the Race motor takes it up a notch giving a bit more of a kick. A subtle feature that I really dig.

Both systems share a 750w/h battery, offering riders great range. Of course, this also comes with a bit of a weight penalty over smaller batteries, but is well worth it in my book.

The back end of both bikes perform equally well, with a good amount of support on offer and, even on the heaviest of flat landings, there’s no feeling of a harsh bottom out.

Suspension

The Prestige features a 180mm FOX 38 Float 29” Performance eBike edition fork – simple and effective; while the Exonic runs a 180mm FOX 38 Factory Float FIT4 Kashima eBike edition. The Exonic gets the premium gold Kashima coating on its Factory stanchions, as well as dials for a 3-level compression adjustment: Open mode compression adjustment and obligatory Rebound Damping dial.

Although the Prestige’s Performance Elite fork simply has a compression lever with three positions, and a rebound dial, it’s still a top performer and is honestly so simple you can just jump on it and go – sometimes the extra adjustability of a fork like the Factory Fit4 can take a bit more effort to set up properly. Both forks are fitted with the sweet Fox-specific bolt on the mud-guard. Between the two bikes, I really like the simplicity of the Performance Elite fork – just dial in the air pressure, hop on and ride! Out the back, we find the FOX DHX2 Factory 2Position coil-sprung damper on the Exonic, and a FOX DHX2 Performance Elite 2-Position on the Prestige. Both shocks are a great option for a bike like this.Providing an exceptionally plush 170mm of rear wheel travel, the Factory level shock has just a little more of a buttery feel thanks to its Kashima coating. With high- and low-speed adjustments on compression, and rebound on both shocks, there’s plenty to twiddle with. Both shocks also have a lever to firm up the compression which, once flicked, calms the shock down while climbing. It’s not a lockout as such, but does heavily damp the compression of the shocks. I’m not entirely sure the nuances of the tuning will be that noticeable when you take into account the large tyres and the weight of the bike; some adjustment is good, but more doesn’t mean ‘better’ in all cases. Although, if you’re keen on a bit of tuning – and happy to spend the time – the results should be stellar.

The back end of both bikes perform equally well, with a good amount of support on offer and, even on the heaviest of flat landings, there’s no feeling of a harsh bottom out. Being coil-sprung, the back end is far more supple than a more commonly found air shock and thus tracks super well, keeping the wheel glued to the ground and holding its line across rough terrain. Between the two shocks, the difference when out riding is negligible and, if blindfolded, I doubt anyone could feel the difference between the two models. Depending on rider weight and preferred rear suspension feel, it’s likely a different spring may need to be fitted to achieve optimal performance – not quite as easy as just whipping out a shock pump.

Drivetrain

KTM knocked it out of the park when selecting drivetrains for these bikes. The Exonic gets a top shelf SRAM AXS XX T-type derailleur, chain and cassette. On the Prestige, we get the SRAM GX AXS T-type derailleur, chain and cassette. Both these drivetrains are ideal for an eBike; with their pin-point precision and ability to shift under power, nothing comes close to how positive they feel out on the trail and I’ve been happily snapping through gears whenever I felt the need. Handily, both bike’s derailleurs are powered by the bike’s battery, rather than the normal AXS batteries. The downside is, if the bike isn’t turned on the gears won’t shift, so should something go drastically wrong, you’ll be single-speeding home. The gear range is ample; there’s no need for any lower gears, and there are more high ratios than anyone would ever need, particularly as pedalling any faster than the 32km assistance limit is a total chore and this limit is met with two to three gears remaining, depending on your cadence.

Dropper Posts

A 150mm dropper post on a Large bike? You read that correctly. Both bikes have a 150mm dropper fitted. The Exonic gets the slick RockShox Reverb AXS, and the Prestige – a FOX Transfer Performance level post. Both are great units, the Reverb AXS gets my vote between the two, with its AXS button actuator mirroring the AXS XX shifter pod. A click of a button makes it all very easy to use. A tall rider will likely want to put a longer drop post on the bikes, but for shorter-legged riders like myself, options will be limited by the frame’s 450mm seat tube length. I found this a bit of a pain, as I’d really like a 170mm drop at least and may struggle to find one to nail my optimal saddle height without interference from the frame’s seat tube.

Overall, the bikes excel on flatter terrain; shining on slower, technical trails more than wide open, fast and chunky steeps.

Wheels

Wheels on eMTB are generally not something to sing about but, in this case, we see a couple of solid and distinctly different options. The Prestige has a pair of KTM E-Team Trail rims (made by DT-Swiss – and they appear to be the same as one of their downhill models) on DT 350 Hybrid hubs. The Exonic gets a pair of very swanky, carbon DT Swiss HXC 1501 SPLINE rims on DT 240 Hybrid hubs. Both wheelsets are very stout and, as you’d expect, the Aluminium rim of the Prestige gives a bit more forgiveness. But, with its faster-engaging rear hub, stiffness, weight, and overall swag-factor, the Exonic’s carbon wheelset gets my tick. The only question mark is, being carbon, does the longevity of the rims come into question – particularly if you love bashing rocks? Fortunately, DT Swiss has a good warranty policy!

Brakes

The combined weight of an eMTB and its pilot travelling at speed is a lot to slow down. KTM have specced great brakes on both bikes, but a bit of an oversight sees them both let down in the braking department. Prestige has the tried-and-true Shimano Saint 4-piston downhill brakes; they bed in quickly and offer consistent power and performance. The Exonic level gets a set of Magura MT7 HC3 4-piston brakes; they have great adjustment and, once set up, they feel nice, solid and consistent; the levers feel comfortable and ergonomic once the multiple adjustments are dialled in. Both bikes get a 203mm rotor up front which is great and offers enough bite and overall power for any scenario. Unfortunately, both bikes have just a 180mm rear rotor, simply not enough to effectively slow the momentum of bike and rider. During long steep descents the rotor overheated and the brake just lost power.

Geometry and Handling

The head angle sits at 64.1 degrees, pretty normal for a bike with 150mm of travel. The upside of this is it keeps the bike nimble in most scenarios, even on mellow or flat trails. The bikes climb well, their shorter reach and comparatively long stem (50mm) help keep weight on the front and keep the wheel on the ground.

Thanks to a high anti-squat, the bike sits up in its travel while climbing steep sections. In scenarios like this, when there’s high torque through the drivetrain, a lower anti-squat would see the suspension being sucked into its travel – not something to worry about on these bikes though. Once accustomed to the weight, jumping the bikes was fun and you’re able to use a bit of body language to float sizable jumps and make sure of smooth landings. Nothing strange stood out while hitting take-offs, but it does take a little to adapt to the weight.

Overall, the bikes excel on flatter terrain; shining on slower, technical trails more than wide open, fast and chunky steeps. I found the bike easy to corner and quick to change direction, thanks to its short wheelbase and mullet wheels; but on steep, rugged trails, I couldn’t get confident – likely a combination of the underpowered rear brake, short reach and longer stem than I’m used to.

Overall Thoughts

“A mixed bag” is how I’d sum up the Macina Prowler Prestige and Macina Prowler Exonic bikes. Outside of a couple of minor things, the component package on both bikes is solid. It does feel a little like KTM has taken the geometry of a shorter travel eBike, aimed at trail riding, and stretched the travel out to that of a heavy-hitting all-mountain bike. A bike with 170/180mm of travel would normally have longer, slacker and lower geometry than we see here. The downside is that a bike with that geometry wouldn’t be as good as the Prowlers are on mellower trails, or for ‘touring’ style riding where there’s as much climbing and flat as descending. So, where does that leave us? These bikes are perfect on what I’d call the ’middle ground’ of trails: not the flat, smooth trails of one end of the bell curve, or the steep, rough technical trails at the other end of the scale, but right in the middle; the riding a majority of us spend most of our time doing, pure trail riding. Rolling trails, some technical, some rough – but not extreme.

If money was no object and I wanted a top specced, high end eMTB with the best drive nit money can buy, then I’d jump on the Exonic. If my budget couldn’t quite stretch that far then the Prestige bike is an exceptional alternative.

Trek Fuel EXe 8 GX AXS T-Type

Words Georgia Petrie

Images Cameron Mackenzie

RRP $12,499

Distributor Trek NZ

The past two years have been abuzz with exciting product launches for the superlight (SL) eBike nerds among us. Between the likes of Transition, Orbea, Specialized and more recently, Santacruz, the lightweight eMTB market is now a smorgasbord of “too light to be true” offerings. And, with each new bike launch, the discreetness of the “e” factor across the market blurs the line between acoustic and electric even more. Motors and batteries are becoming more compact whilst, simultaneously, the power, torque and range abilities are increasing exponentially, to the point the reliability of my once sharp “eMTB radar” is becoming a little questionable.

Trek’s Fuel EXe takes ’stealth’ to a new level and their alloy offerings combine budget and performance to create an economical yet hard-hitting package that will tempt the appetites of even the purest acoustic bike riders out there – you might want to unblock your ears for this one!

With a chassis deriving from the popular and proven Fuel EX, the Fuel EXe electrifies it’s do-it-all acoustic counterpart, giving riders the ability to do more: turn your post-work lap into two, remove the “dread” from climbs, and descend without the clumsiness of traditional full power offerings. Sporting 150mm front and 140mm rear travel, the bike is a capable descender that’s isn’t afraid of tackling jumps, drops and steep grade five descents far above its paygrade, whilst maintaining nimble-ness at its core. It’s a comfortable, versatile all-rounder that’ll leave you wanting more – and with a punchy 360Wh battery and 50Nm torque motor to boot, why not?!

Power is delivered smoothly and naturally – there’s no sudden jerk forward when the assistance kicks in, and it really does feel like you’re just riding a non-powered bike with a little pat on the back for some extra help.

eBike Features

The Fuel EXe is powered by the TQ-HPR50 motor, which has made quite the name for itself within the lightweight eMTB segment, sported by the likes of Mondraker, BMC, Cube and Unno to name a few. Producing 50Nm of torque and 300-watt peak power combined with a 360Wh battery, the TQ-HPR50 is a punchy package – enough grunt to get you up nasty climbs, and enough battery for a decent after-work pedal and then some. Comparatively speaking, these numbers reflect a blend of those seen on competing lightweight offerings. The torque output mirrors the Specialized Levo SL Gen 2 but the Fuel EXE has a slightly higher battery capacity, while the Shimano EP8-RS seen on the Orbea Rise matches the Fuel EXe in battery capacity, but sports slightly higher torque at 60nm.

It’s little wonder the Fuel EXe masks its eBike nature so well, the battery and motor weigh in at just 1.85kg and 1.83kg respectively – our EXe 8 GX AXS T-Type review model weighs in at 20.25kg/44.65lbs, which is very respectable given the bike’s alloy frame, budget friendly componentry and removable battery. Riders can also purchase a 160wh range extender that sits discreetly in the bottle cage, providing an extra one to two hours of juice for only 950 extra grams of weight.

Adding to the sleekness is the TQ display that’s cleanly integrated into the top tube, which can be adjusted to display your preferred units. This is paired with a simple three button handlebar mounted remote, used to toggle between the bike’s three primary modes – Eco, Mid, High and Walk. The max power, assist level and pedal response for each mode (except for Walk) can be tuned using Trek’s Central app, where you can also track ride statistics, activity and even get recommendations on tyre and suspension pressure.

Out of the box, I felt the stock motor tune provided not only efficient, but natural assistance. Having ridden a range of different lightweight and full power eBikes, a key learning I’ve encountered is that whilst two motors might have largely similar numbers on paper, when it comes to power, it’s how that power is delivered that truly differentiates the experiences across the SL offerings. The TQ-HPR50 delivers power instantly but smoothly – instead of the bike jerking forwards with each pedal stroke, it provides a gradual increase in power that’s akin to someone giving you a light push on the back.

It’s also by far the quietest motor I’ve ridden to date, delivering power almost silently and descending with equal quietness – whilst it doesn’t bother me, I’m certainly aware that the decibel level of a motor is quite contentious a topic for some SL shoppers, so this is great news for those not so keen on listening to their bike whirr away whilst pedaling.

I was highly impressed with the bike’s performance tackling chundery roots and rock gardens, drops and jumps – you’d be forgiven for thinking the bike has 10mm more travel than it really does.

Geometry

The Fuel EXe sports do-it-all geometry that’s “just right” – an aggressive enough 65.3° head angle meaning it doesn’t shy away from steep, technical trails, paired with a 1216mm wheelbase that plants the bike nicely on rough, open terrain, particularly in combination with the damped feeling of the alloy frame. At 77.3°, the seat angle is a welcome addition on a bike that sits in the SL market – this is a touch steeper than competitors such as the Levo SL (75.8°) and Orbea Rise (76.5°), making it a comfortable all-day climber and enabling the front end to remain planted on steeper ascents.

With a wheelbase of 1216mm, the Fuel EXe evokes a sense of stability on wide-open descents – you’ll struggle to feel unstable on this bike or hit the point of ’wobbliness’ that can occasionally be felt on mid-travel range bikes. Paired with a reach of 459mm, the overall size of the bike does feel slightly on the big side relative to other SL offerings, and if you’re in-between sizes, I’d highly recommend swinging a leg over one first. I felt that these characteristics didn’t penalize the bike’s performance, in fact I quite enjoyed the stability and planted feeling that came with the slightly longer bike – overall it felt really balanced and was a confident descender.

Climbing

Now for the nitty gritty stuff – ride performance. Having ridden a range of SL and full powered eMTBs, I was beyond excited to swing a leg over the Fuel EXe – living in Christchurch, we’re fortunate enough to have access to the steeps of Victoria Park, the wide-open flow trails of the Christchurch Adventure Park and the backs and beyond of Craigieburn – an eMTBer’s paradise!

When it comes to overall riding position, Trek have created an excellent balance between a tackle- anything descender, and a comfortable all-day peddler. The steep 77.3° seat angle seats you comfortably, upright and over the bike’s front – you aren’t fighting to keep the front wheel down on steep pitches and it’s extremely comfortable spinning up gradual climbs. The long wheelbase made it a little cumbersome on tight corners – I needed to be quite careful when entering corners and target my lines carefully on technical ascents to ensure I didn’t get too hung up in tight spots. There were a couple of instances where I couldn’t quite make it up the technical switchbacks of my local climb trail – a combination of wheelbase and motor power. I also struggled to get the 150mm Bontranger Line dropper post high enough – if you’re a longer limbed person like me, you may find this a little short, particularly when paired with the bike’s short 73.3mm standover height.

The TQ motor had a unique power delivery relative to other SL motors, such as Shimano’s EP8 or Specialized’s 1.2. Power is delivered smoothly and naturally – there’s no sudden jerk forward when the assistance kicks in, and it really does feel like you’re just riding a non-powered bike with a little pat on the back for some extra help. An interesting observation was that this bike requires quite a high and specific cadence point to generate optimal assistance from the motor – there were a few occasions on steeper climbs where I felt myself having to spin pretty hard to maintain optimal power delivery.

Additionally, whilst the Fuel EXe sports comparatively higher battery numbers than its competitors, the way that power is delivered seems to draw from the battery slightly more than other SL motors I’ve sampled – I ended up with 10% less range on one of my favorite one hour eBike loops than the likes of the Orbea Rise and Levo SL Gen 2. This wasn’t an issue for those quick 1.5 – 2 hour loops from home, but it does mean you’ll need to plan your route carefully should you wish to tackle any slightly longer days in the saddle. As I would with any SL eMTB (depending upon manufacturer), I’d highly recommend purchasing TQ’s range extender which sits perfectly and subtly in the bottle cage, giving you an extra 160wH of battery and alleviating those “range anxiety” moments.

The 12-Speed SRAM GX AXS transmission was an absolute delight, and an excellent drivetrain choice from Trek. I’m a firm believer that wireless drivetrains shine on eMTB’s, particularly those in the SL class, as you’ll often be alternating between motor modes and gears to optimize forward propulsion and power delivery – efficient shifting with immediate actuation makes gear selection a breeze. The bike shifted exceptionally well under heavy load, and I never once had an issue with gears slipping or my chain threatening to drop.

Paired with SRAM’s robustly machined GX cranks, the drivetrain performance makes you forget you’re on the “entry level” alloy model and, at 165mm in length, you’ve got enough clearance to avoid pesky peal strikes, which are much more common on e-mtb’s due to their lower bottom bracket heights. Plus, the Fuel EXe is cleverly designed so that the main battery serves as the derailleur’s power source, meaning you don’t need to worry about remembering to check battery levels. On the flip side, however, it does mean that should your battery run out during a ride, you won’t be able to change gears, which could mean a long ride home or back to the car for some – these bikes are light, but trust me, you’ll still know about it when the battery dies!

If you’re like me and a busy schedule means limited riding, this bike enables you to cover ground much more efficiently whilst still getting a great workout in, meaning you get to ride more, especially the best parts – the descents!

Descending

Descending, the Fuel EXe comes alive. It excels on wide-open descents, maintaining a planted, compliant feel and isn’t intimidated by big rocks, or venturing into Grade 6 trails. I was highly impressed with the bike’s performance tackling chundery roots and rock gardens, drops and jumps – you’d be forgiven for thinking the bike has 10mm more travel than it really does. The alloy frame strikes a nice balance of being stiff without losing feel of the terrain beneath you, and the wheelbase creates stability that evokes a certain level of confidence over and above other bikes of this travel range.

The Fox 36 Rhythm was a breeze to set up, and the added GRIP dampener helped with small-bump sensitivity – hitting drops and jumps was akin to lounging on a Lay-Z-Boy. It’s plush and the bike really sits into the travel on big hits – one may think, “bold bruiser” as opposed to “nimble dancer” when characterizing the ride feel, which isn’t a bad thing at all on the right trail – this bike has got your back! Whilst more of a “point and shoot” descender that’s perhaps not as responsive as other SL options, such as the Levo SL or Orbea Rise, the Trek tackled my local Christchurch steeps and rock gardens with ease, making light work of trails that, in theory, should be well beyond its paygrade.

The Fox Float X Performance series shock is the perfect complement to the 36 fork – these shocks pack some serious punch and tackle small bump sensitivity with ease, and the dampening is just superb. In my experience, with its stoic build and piggyback reservoir, The Float X considerably elevates the descending performance of any do-it-all mid-travel trailbike, and its extensive adjustability means that it can be tuned out-of-the-box to a wide variety of rider types and terrain.

The SRAM DB 8 4-piston brakes were new territory for me but fitting for the Fuel EXe, self-described by SRAM as being “simple” and “robust” – a perfect complement to the bike’s tough, sturdy characteristics. Whilst initially hopeful as I set off on the first descent, a mellow tech-blue trail at Christchurch Adventure Park, the powerful bite that I experienced at the start of the trail quickly faded and unfortunately left my hands pretty cramped at the trail’s end as I was pulling hard to try and control my speed. Although the Fuel EXe’s beefy 200mm rotors and large levers were an uncommon, but welcome choice for an SL eMTB, these features weren’t quite enough to offset the limited braking power that the DB8’s offered on longer, or steeper descents, and I would’ve preferred something with a little more bite. Undergunned brakes are not unique to the Fuel EXe – brakes are a component that often leaves a lot to be desired when it comes to many of the out-of-the-box eMTB’s; SL or full power, that I’ve ridden thus far. Due to the extra weight of the eMTB, decent stopping power plays a crucial role in how the bike feels, and underpowered brakes can make a bike feel cumbersome and arduous, which is particularly noticeable on an SL eMTB like the Fuel EXe, where you want to bridge the gap between acoustic and electric, not extend it.

Being a longer limbed person, my only gripe when descending was the 150mm Bontrager Line Dropper, which I found to be a little in the way – a slightly longer 170mm drop option would’ve been a welcome addition. We also found the cable actuated dropper post lever to be a little fragile, with the cable detaching from the mechanism on a couple of occasions, rendering the post unusable trailside. On both occasions, remediating the issue unfortunately required no option other than to drop the motor out (a finnicky job, to say the least!) to reconnect this. Routing non-electronic dropper posts is a cumbersome exercise across the eBike board, so this isn’t unique to the Fuel EXe, however, it does mean that ideally the spec’d dropper post should be as reliable and trouble-free as possible to avoid any technical headaches!

Overall thoughts

The Fuel EXe is an excellent out-of-the-box package that represents great value for money and delivers a ride experience that packs a punch, especially on the descents. With its quiet motor, subtle assistance and stealthy appearance, the bike is a great stepping stone into the wonderful world of eMTB for those wanting to get the most of their ride, whilst maintaining the maneuverability, handling and responsiveness of an acoustic bike.

So, who is this bike for? If you’re on a tight schedule and you’re wanting to squeeze as much riding as possible into a short space of time, this bike is for you. Or perhaps, if you’re looking for a ride experience that mirrors that of your acoustic bike as closely as possible, this bike is for you. If you’re a weekend warrior who often ventures out to the mountains for multi-hour or multi-day backcountry adventures, then this bike perhaps isn’t for you, although the Fuel EXe’s range extender does provide a considerable amount of range anxiety alleviation, depending upon the duration and terrain of your routes.

Whether or not the Fuel EXe is for you depends on the type of riding you’re doing, the type of rider you are and, realistically, how long you often ride for. For me, I loved that the Fuel EXe meant the difference between fitting in a decent ride and not riding at all. If you’re like me and a busy schedule means limited riding, this bike enables you to cover ground much more efficiently whilst still getting a great workout in, meaning you get to ride more, especially the best parts – the descents! Because who doesn’t want to ride their bike as much as possible, right?

Destination: Coronet Peak

Words & Images Riley McLay

Famous Brazilian footballer, Pelé, once said; “Success is no accident. It is hard work, perseverance, learning, studying, sacrifice, and most of all, a love of what you are doing”. MeekBoyz Racing’s focus on success has led them to join forces with Coronet Peak, taking on the role of ambassadors for the bike park. Being able to perform at a high level requires having the best riding opportunities and access to quality facilities.

This relationship was an obvious choice for Coronet Peak and a great fit for the boys, as both parties share a lot of key values, along with their love of all things two-wheeled. Not only is it an opportunity to support Queenstown locals with chasing their dreams of racing, Coronet Peak also feels they are both in a position to grow together and help progress the boys racing while continuing to give Coronet Peak exposure on the international stage.

Coronet Peak was New Zealand’s first commercial ski field, opened in 1947. It originally hosted one single tow rope, which would get skiers up the snow-covered slopes of the mountain. A stark contrast to today’s multi chairlift operation that spans the majority of the hill. In recent years, Coronet has switched their focus to becoming an all-year outdoor recreation destination,with plans to greatly expand upon their current vast network of some of Queenstown’s best downhill, enduro and cross-country mountain bike trails. Giving riders a variety of options to accommodate from beginner to pro level abilities. Coronet Peak is only a short 20-minute drive from Queenstown central, making it easily accessible to locals and tourists visiting the mountain biking mecca. The ski area is instantly recognisable from all angles as you arrive into the Whakatipu Basin. As you snake your way up into the alpine, you are met with the bright glow of tussock grass covering the hillside. The faintly flowing shadow of trails give the only hint of activity amidst the ruggedness of the high country. As you get closer to the top, the flurry of other riders increases and the sound of laughter breaks the serenity. Coronet Peak’s summer operations allows it to take advantage of what it has built upon over the many winter months they’ve experienced, and continue to provide a premium product for the mountain bike community.

The main base building consists of a fully staffed indoor cafe. Sitting on the outdoor deck and watching fellow riders go past, is the perfect way to relax with a bite to eat or cold refreshment on a warm summer’s day. The base building also features a fully stocked bike workshop to tend to any issues you may have out on the trails. This also gives patrons access to Coronet Peak’s fleet of rental bikes and ensures your rental is fine-tuned for your preferences, and maintained throughout the day. The flexibility of pass options allows riders to easily plan their day of riding, with day and 4-hour passes available. Experiencing the magic of golden hour up Coronet is not to be missed, with a sunset pass from 4-8pm available on Thursdays and Mondays. A perfect way to unwind after a busy day and make the most of the late evenings. For those less experienced, Coronet Peak also undergoes regular patrols, ensuring peace of mind, knowing that assistance is never far away should you run into any issues.

I can see why the mix of fast and well-built jumps and turns set to a stunning backdrop, attract these international riders who make the mountain pilgrimage every year.

Coronet’s newly installed six-seater ‘Coronet Express’ chairlift, with a specifically designed bike rack system, quickly delivers riders to the peak. For those who aren’t into biking, there are enclosed gondolas for a more comfortable alternative. At the top, riders and outdoor enthusiasts alike are met with breathtaking views of the Whakatipu Basin. The sightseeing lookout is the ideal place to take in the expansive view of the valley below. These views extend to the very peak of Coronet, looking out to a full 360 panorama of the surrounding southern alps. From the peak of Coronet, riders can explore three trails: Coronet XC, Coronet DH, and the Dirt Serpent trail.

The Coronet XC is the longest trail on the upper part of the mountain. Starting under the chairlift, this grade 3 trail takes you right out towards the north side of the ski field boundary. With a series of switchbacks and varying singletrack, this trail is the perfect warmup for a day of riding. It is also a great starting point for less experienced riders, as this trail is a perfect introduction and opportunity to acclimatise yourself to the famous Coronet Peak dirt. It’s extremely grippy texture (even when wet) is another characteristic that sets Coronet Peak apart from other trails in the Queenstown area – and is an absolute delight. This trail also gives you access to the Slip Saddle, a grade 5 trail that carries you all the way into the nearby Arrowtown township, via the Bush Creek trails.

Coronet DH, arguably the most well-renowned trail of the three, begins directly as you hop off the lift. The grade 5 black trail is the most direct way down the hill. Originally sculpted in 2006, the track travels through the alpine tussock and makes use of the rugged terrain to give riders more of a challenge, with a combination of high speed and technical sections. It’s also host to iconic features such as the Canyon Gap and Rock Slab Drop that fully utilise the landscape. These features can make for some thrilling moments.

Adapting to the speed of the trail does take a lap or two, but once you memorise the order of things, you’ll see why the trail has gained the recognition it deserves. It was specifically constructed with downhill racing in mind and frequently hosts races on the local club and national level. Coronet DH is a magnet for overseas professional riders in the summer months, as it is the perfect training ground for the northern hemisphere off-season. It isn’t uncommon to see some of the world’s fastest racers lapping out the track on any given day. During one sunset session, I even spotted the likes of Laurie Greenland and Danny Hart, along with at least ten other world cup racers, ripping down the track. I can see why the mix of fast and well-built jumps and turns set to a stunning backdrop, attract these international riders who make the mountain pilgrimage every year.

Aeroe Spider Handlebar Cradle

Words Lester Perry

Images Henry Jaine

RRP $129

Distributor Southern Approach

With our Mt Starveall mission penned in the calendar, I began pulling gear together for the trip. Sorting through my stuff, it was obvious none of my existing bikepacking gear was quite ideal for a trip like this – my regular strap-on bags just wouldn’t cut the mustard on technical and rough trails; I needed something stable and secure.

Aeroe came to the party and sent me out a Spider Handlebar Cradle and dry bag, and an equivalent setup for Kieran, my mission companion for the trip.

Aeroe set out to create a simple-to-use system for carting gear on your bike, initially developing ‘The Freeload Rack’, which they ultimately sold to Thule in 2011. Not long after the sale, they began quietly working on a new gear-carrying system, presumably waiting until after restraint of trade agreements lapsed to launch under the Aeroe brand. Designed for every mission, from a two-block commute to work to a two-month, multi-country epic, it’s a pretty versatile system – so can be used any time you need to carry gear on your bike, bringing down the cost per use. The entire system consists of the handlebar-mounted Spider Cradle we used during our trip, the Spider Rear Rack, and the more recently introduced Spider Pannier Rack, with the associated dry bags. The entire system is modular, meaning parts of each rack can be swapped over, allowing multiple mounting configurations and helping you to balance the load, or separate gear however you like. The cradle can also be attached to a fork, throwing open the possibilities for how much cargo you can carry.

Compatible with almost any bike, the Spider Cradle was simple to fit to the handlebars. The cradle arrived ready to strap the dry bag on at right angles to the bars (ideal configuration for a fork). I wanted the bag parallel to them so, after a quick disassembly to get the configuration right, I attached the two straps, one on either side of the stem, and tightened up the two 5mm bolts – a quick and stress-free process. There are loads of adjustments on offer, so regardless of the diameter or shape of your handlebars, the cradle should be compatible, even if the handlebar or fork is not completely round. The ease of installation and removal makes switching between bikes or putting away after a mission a cinch.

Access to the bolt heads is limited, so I’d recommend a standard L shaped Allen-key to speed up the process (although a multi-tool does the trick, but isn’t ideal). If you run a stem with a particularly wide face plate, it’s worth a quick measure-up to check the cradle will sit comfortably over it. The cradle feet barely had room to fit over Kieran’s stem – let’s just say it was an ’interference’ fit and required a bit more persuasion to fit correctly than on my marginally narrower, more regular stem.

Constructed from glass-reinforced nylon, the Spider Cradle system weighs in at 464g and can carry up to 5kg of additional load. There are two standard dry bags offered by Aeroe; the 8-litre I used, and the 12-litre used by Kieran. The sturdy bags are made with small sleeves to allow the cradle straps to be fed through them, keeping the whole load stable and secure. Any old bag could be used, but I doubt it would be as secure – or offer the same peace of mind – as the Aeroe bags. The beauty of using a roll-top dry bag is the ease of access – depending on how tightly packed it is, there’s no need to remove the bag from the cradle – just unroll the end for easy access.

After being rattled and bumped around during a solid couple of days out on the trail, the bags show very little sign of use and I can’t see them having any issues, provided they’re strapped securely; it’s doubtful the bag would ever wear out.

My Aeroe bag was crammed full with a bivvy bag, sleeping bag and Jetboil style cooker… no room for snacks in there! Kieran’s Aeroe bag had a sleeping bag, sleeping mat, and large jacket – with room for more. To keep our bikes as light as possible – and knowing we were in for a lot of hike-a-bike – we put the remainder of our gear into CamelBak packs. Our setup worked well, and I think we could have scraped through two nights away with no resupply of food given how light we were travelling. Any more nights and we would have needed additional space for food, maybe using the Rear Spider Rack and an additional bag just for food and snacks.

Some gear just works like it should and it’s obvious the designers have thought through multiple different scenarios, solved problems and answered questions.

I was pleasantly surprised at how solid the cradle was, even under some heavy impacts, stutter bumps and cased jumps – it stayed put, right where I’d attached it, with no noticeable movement or slippage.

The extra weight on the front wheel was noticeable to begin with, when cornering, but after just minutes in we’d adapted and it didn’t detract from the ride – until we tried to lift our bikes onto our backs for a hike-a-bike for the 20th time! So much additional weight on the front wheel made jumps feel a bit weird and nose heavy. Again, we adapted to the feeling, but it was still noticeable. What was amazing was how much extra front wheel traction the weight gave us – so confidence-inspiring and not something we expected at all!

I haven’t tried the Spider Cradle on a drop bar bike yet, but would assume it will work fine, although depending on how cables are routed; they may foul with the cradle mounting straps, but only time will tell.

Some gear just works like it should and it’s obvious the designers have thought through multiple different scenarios, solved problems and answered questions. The Aeroe Spider Cradle is one such item; I can’t fault it, it does what it says on the tin and stands up to some abuse. I’d recommend this setup for anyone looking to cart gear on their bike, particularly if you’re riding technical MTB trails – I’d be surprised if other systems would be quite as solid. I can’t wait to take the setup out on some more missions!

Starveall or bust

Words by Lester Perry

Images by Henry Jaine

WHILE ON A PREVIOUS TRIP, NELSON LOCAL, KIERAN BENNETT, AND I HAD DISCUSSED THE CHALLENGE OF DOING MULTI-DAY MISSIONS, OR SIMPLY EVEN SOLO OVERNIGHT TRIPS, WHILE JUGGLING WORK AND FAMILY COMMITMENTS. LET ALONE TRYING TO LINE OUR CALENDARS UP TO DO THEM WITH SOMEONE ELSE WHO WAS LIKELY IN THE SAME BOAT. SINGLE- DAY RIDES WERE GREAT, BUT REGARDLESS OF HOW EPIC THEY ARE – OR AREN’T – AN OVERNIGHTER HAS A CERTAIN ALLURE. WE TOSSED AROUND THE IDEA OF ME ARRIVING ON AN EARLY FLIGHT, DOING A FULL-DAY RIDE FROM NELSON AIRPORT TO A DOC HUT FOR THE NIGHT, THEN DEPARTING ON A FLIGHT LATE THE FOLLOWING DAY, AS A QUICKFIRE WAY TO PULL OFF AN OVERNIGHT BACKCOUNTRY MISSION.

Chatting with Kieran, he reckoned Mt Starveall and the Starveall track could be a worthy option, but details were scarce.

I’d heard rumours of people riding Mt Starveall in the past, so went on a hunt for more info. Indeed, people helicopter up to the summit and descend to the Hackett car park. Judging by the couple of aged YouTube videos I came across, it looked like a proper backcountry descent; things were looking positive. The internet offered up further details from people who had done the descent after accessing the trail from deeper in the Richmond Range, although only one blog post gave confirmation that people had actually clambered their way up the Starveall track before descending back down. Without a heli drop, an ascent on Starveall sounded like it may turn into some sort of twisted cross-fit style bike-carrying mission. But there was only one way to be sure: to physically take it on.

Dates were locked in, flights booked, and the route confirmed – there was no bailing out now. Late January, I spied a Strava ride from a friend; a heli drop from the top of Starveall. A few messages backwards and forwards confirmed it was a worthy trip, but also that we were deranged to be considering the hike-a-bike to the top.

Four-twenty in the morning is not a fun time to be woken for any reason, but needs must. By 4:30am I was dressed and had prepared a bottle of hydration mix and a quad shot of strong espresso to get me through the nearly two-hour drive to Auckland Airport. How ridiculous is it that it’s cheaper by a few hundred dollars – and almost quicker! – to drive nearly two hours, pay for gas and parking, and fly to Nelson from Auckland, than from my local Hamilton airport?! An overcooked breakfast muffin and a flat white; the obligatory Cookie Time and black coffee onboard, and after spinning for an hour and a half, the ATR 72’s props came to a shuddering stop outside the Nelson terminal.

With Kieran Bennett laying the initial foundation for my route, it was only fitting that he came along; stupid ideas are best shared with friends and if it all went bad then I had someone to share the blame with. After a few minutes of spinning Allen keys, my bike was assembled. Once again, I attempted to whittle down my gear for the trip; necessities and nice-to-haves. Space was tight and we wanted to travel light. I stuffed what I could into a handlebar-mounted Aeroe drybag, filled every nook and cranny of a CamelBak HAWG Pro backpack with the remaining gear, and we were good to go.

By 10:30 am we were ready to roll, but first; coffee and a butane canister. Butane for cooking, nothing nefarious. A quick stop at Bunnings ticked the final boxes on the admin list, providing the gas for the cooker and coffee for the body. It was game on. Continuing on the bike path, we began the mellow climb towards Silvan MTB Park. The day was warming up and the sun was out. It was here I remembered my sunscreen was still sitting at home.

Winding our way up through the forest of Silvan, our chat was flowing thick and fast. We calculated and theorised how long we’d take to reach our destination: Starveall Hut. It was getting hot and I was already sweating what felt like litres, yet we’d barely put a dent in the day. How long would my three and a half litres last me? If I kept drinking at the rate I was, not long!

As we reached the top of Silvan, we made the first of many snack stops. Half a sleeve of Oreos between us, a muesli bar and some mixed lollies. Over fistfuls of sugar, we broke out the maps again and were speculating how long the day would be. One thing was becoming apparent by this point: we had no accurate idea.

The quest for a route to suit the timeframe, began by spending time in my trusty Topo Map app. Focusing on the Richmond Range, I was hopeful I’d find a hut we could ride to directly from the airport. Tracing hiking routes on the map, cross-referencing with DOC information, Strava heat maps and the Nelson Trails website, there were a few options on the table, but I needed some local knowledge.

We dropped over the back of Silvan, descending gravel roads into Aniseed Valley towards Hackett carpark and the beginning of Hackett track. The track was a mostly mellow, well-formed affair and, aside from a couple of chunky sections for a few metres, it would be passable on a gravel bike. The track winds its way beside Hackett Creek for 5.8km, then spits you out in a grass clearing at the Hackett Hut. I’m sure the gas cooker and the half-tub of Vaseline that remain in the Hut have some tales to tell. With places to be and bikes to carry up hills, we pressed on. We left the hut and went from the mellow comfort of the gravel trail, to the unkempt wilds of the Starveall Track.

The story goes that Mt Starveall gained its name in the 1800’s after a stockman was looking for a route to drive his sheep from Nelson to Wairau Valley, attempting to dissect the Richmond Ranges rather than take a longer, albeit easier route around the valleys. Reaching the summit of what we now know as Mt. Starveall, he found there was no suitable feed for his sheep. Dismayed, he proclaimed the mountain would “starve all” his flock. Seems the name stuck.

I’m no stockman, and we had no sheep to take anywhere, but as Kieran and I were crossing the river for a third time in only a couple of hundred metres, I was wishing we could “starve all” the people who decided the trail needed to cross the river some nine, or maybe it was ten, times in a kilometre of track. Halfway across the river at one point, we met a hiker descending; a foreigner on his quest to complete the Te Araroa trail (which Starveall track is part of). The look of confusion on his face said it all: he seriously thought we’d lost the plot and was verging on visibly distressed that we were about to carry our bikes up this mountain. We silently wondered if maybe he was right.

I’m still surprised, after so many stream crossings and hundreds of footsteps sketchily balanced atop rocks that were at times smaller than a foot, that – thanks to grippy-soled, modern riding shoes, and us having the balance of ballerinas – we both managed to keep our feet dry!

Leaving the prospect of falling in a stream behind us, the gradient of the trail pitched up. Not just a bit but, for a period, a lot. Picture ‘climbing a hundred-metre-long staircase with your bike on your back’ sort of steep. We were into the meat and potatoes of our mission.

Leaving the prospect of falling in a stream behind us, the gradient of the trail pitched up. Not just a bit but, for a period, a lot. Picture ‘climbing a hundred-metre-long staircase with your bike on your back’ sort of steep. We were into the meat and potatoes of our mission.