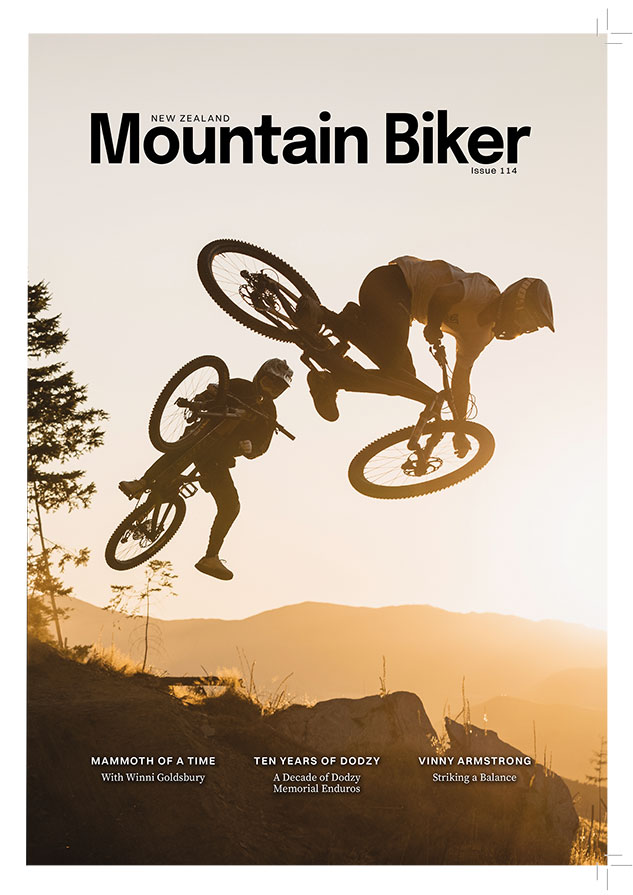

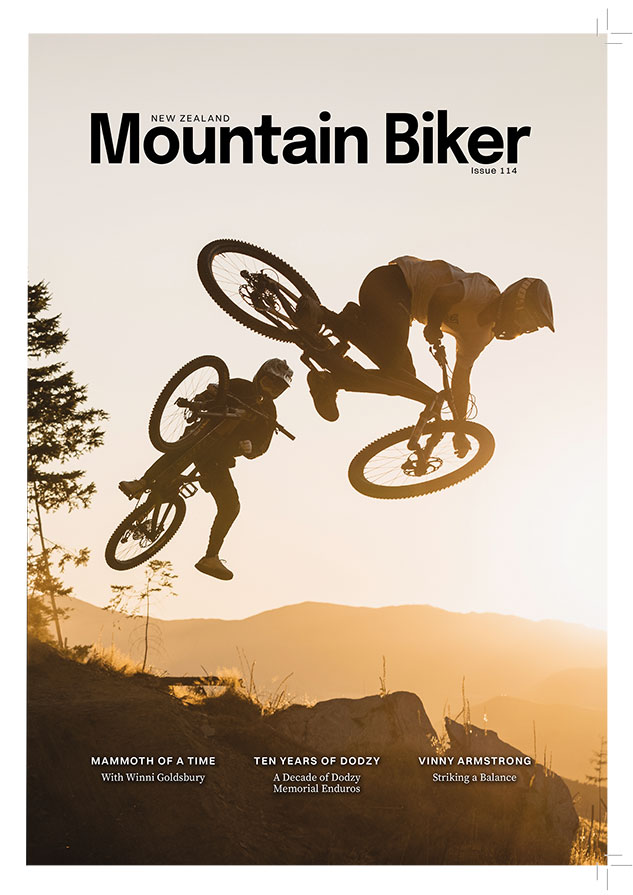

First Impressions: Specialized Turbo Levo

Words: Nathan Petrie

Images: Cameron Mackenzie

As an unashamed fan of eBikes, I’m always pumped when I get the chance to throw my leg over a new offering from a brand in the space. So, when the opportunity presented itself to try out the highly anticipated new Specialized Levo, I knew it was something I couldn’t turn down. The Levo’s a bike that holds a bit of a special place in my heart, seeing as the first generation one was the first eBike I had the chance to ride. Times have changed a lot since then though, and in the rapidly evolving world of e-bikes I was interested to see how this redesigned Levo stacked up! Pulling the bike off the rack, the first things that are noticeable about the new Levo – aside from its Stumpjumper-inspired styling – are the large Geni shock and the stout downtube. But don’t let either of these things fool you into thinking that the new Levo’s just a two wheeled couch like some full-power eBikes can be. A quick bit of carpark tuning later and it was apparent that the Levo had a lively and responsive feel. At a time where riders are facing the choice between a full-power or lightweight eBike, this kind of responsiveness with the power and range the Levo offers may provide some riders with a bit of food for thought.

A glance over the Levo’s geometry chart and travel numbers reveals where this responsive demeanour might come from. The key figures like head-tube and seat-tube angle, chain-stay length, reach and wheelbase were all pretty standard across the board for our S4/Large size test bike. As with many of Specialized’s gravity-oriented bikes, the head angle, chain-stay length and bottom bracket height can also be adjusted to offer a more customised riding experience. On top of this, the travel – at 160mm front and 150mm rear – is a pretty ideal amount for all-round riding. The weight also feels fairly respectable too; impressive given the large 840Wh battery spec’d on our Pro level build. As has been the case for a while with Specialized eBikes, the overall package is fairly well thought out. The remote – while still wired – is fairly slim and very responsive, and the enlarged touch screen is well integrated into the top tube so you can easily keep tabs on your battery level and power setting. Specialized have added to the versatility of the system by giving riders the choice between either the 840Wh battery we had, or a smaller 600Wh aftermarket option.

On top of this, riders can use the 280Wh aftermarket extender for even more range with either battery. This gives a fairly impressive 1120Wh of capacity at its maximum which should offer plenty of scope for the kind of back country exploring eBikes are good for. The Levo also features an eBike-first in-frame storage option, with a SWAT bag that fits neatly above the battery in the head tube area. The build kit on our Pro level model was also largely what you’d expect from a bike at this price point. From the nicely finished carbon frame to the Factory Fox 38 fork, SRAM XO transmission drivetrain and carbon Roval wheels, the build kit didn’t leave you feeling short changed. The frame and motor were nice and quiet on the descents as well, with no annoying motor or cable rattle to speak of. The only possible area for improvement would be consistently speccing a 200mm dropper post as standard on S4 bikes. While many companies seem to be keen on allowing riders to size up, anything less than 200mm on what would be a large bike is just too short for the average buyer of that size.

While the first ride on a new bike will always be a bit of an unfamiliar experience, having that first ride in an unfamiliar location can really highlight how easy it is to get on with a new bike. For me the first lot of riding on the Levo came in the form of a trip to Dunedin to highlight what the city had to offer as a riding destination. The first outing on the bike at Signal Hill confirmed that the bike is pretty easy to just get on and ride. The predictable handling and suspension performance means that, aside from the usual cockpit adjustments, there’s not much of a bedding in period – or any quirks to get used to. The first thing that strikes you on the climbs, is how smoothly and quietly the bike delivers its ample power and torque. Some eBike motors aren’t exactly stealthy when it comes to putting the power down with a noticeable whine from the motor. This was something Specialized put a lot of effort into when developing the new 3.1 motor. The new Levo also has a decent bump in power and torque over the outgoing model, with that power being maintained over a much wider cadence range. While my first ride didn’t feature much in the way of technical climbs, we did head up a couple of fairly steep sections of single (and double) track. Aside from some unrideable clay patches, these climbs didn’t seem to faze the Levo, even in Trail mode.

The responsiveness that was noticeable in the car park was also put to the test early on at Signal Hill, by rolling through a few sets of jumps. Some full power eBikes can be a bit of a chore to get off the ground, especially with flatter take-offs, and can still feel slightly weighty in the air. Not so with the new Levo. On both the high-speed DH style jumps on the Nationals track, and the more sculpted lips on the Jumps track, the bike was more than willing to get airborne. When in the air it was also easy to move the bike around and get some decent shape – once again, not something that is readily done with all full power eBikes. The bike also performed well on the slippery rocks and roots that we were treated to throughout our time in Dunedin. The bike struck a nice balance when it came to frame stiffness, holding its line well in rough sections but not causing the bike to feel harsh or deflect off a wet root or rock. This stiffness, coupled with the suspension and wheels, made for a comfortable and compliant ride in rough and unfamiliar terrain where you’re not always on the ideal ride line. The revamped Specialized tyres also offered plenty of traction in most places and, when combined with the SRAM Mavens, provided a nice sense of control over the slick terrain.

The outing in Dunedin also provided a good opportunity to put the range of the new Levo to the test, with two decent length rides in one day. While these rides didn’t cover a huge number of kilometres, we did get in near on 1200m of climbing across two locations. This left us with around 27 percent of the battery remaining by the end of the day. I also had the opportunity to try the Levo a bit closer to home, in two different situations that eBikes are good for. The first was more of a power hour-and-a-half on the trails of the Christchurch Adventure Park and Victoria Park. The adventure park in particular can be very harsh on bikes, between the stretches of exposed volcanic rock and the hard pack singletrack littered with roots and rocks. Once again, the Levo provided a smooth and controlled ride on a lot of the rough sections and handled the steeps in both locations without any issue. Another run through some jumps on the adventure park’s O-Zone trail confirmed that feeling of predictability and liveliness that came through in Dunedin.

The second outing was more about tapping into the spirit of exploration eBikes in general are great for. This outing in the Canterbury high country largely featured some lower grade grassland, riverbed traversing and hiking trail. While none of this really challenged the Levo from a motor, battery or suspension travel perspective, it highlighted the general-purpose nature of the bike. Even on less demanding terrain at a more leisurely pace, the Levo never felt like too much bike. The same responsiveness was still there, and the motor still offered decent assistance when cruising along in Eco mode. So, after a bit of time in a good range of settings, I think it’s fair to say that the Levo carries on the lineage pretty well. It’s still that same great all-rounder bike that it’s always been, but with some useful improvements to the power, range, frame and suspension performance. It’s a bike that’s easy to just get on and ride in a wide range of terrain and for a variety of ability levels. Like its lower-powered (Levo SL) and unpowered (Stumpjumper) stablemates, it gives riders user friendly geometry, travel numbers and ride feel that makes it an easy bike to feel comfortable on right away. The combination of reasonable weight, good integration, generous range and quiet, responsive motor certainly maintain its place in the top tier of full-power eBikes.

Leatt Products

Words Lester Perry

Images Jamie Fox

RRP $90—Trail 1.0 Short Sleeve Top | $160—Trail 2.0 Shorts | $230—ReaFlex Hybrid UltraLite Knee Guards

$370—Enduro 2.0 Convertible Helmet

Distributor BikeCorp

Leatt is a brand founded on a quest to offer the highest possible protection, through rigorous research, testing and development. Grown from an idea sparked by Dr Chris Leatt’s mission to protect his then four-year-old son from injury while riding motorbikes, Leatt has become a global leader in research-backed protective gear.

After witnessing the death of fellow rider and friend, Alan Selby, from a suspected neck injury in a motorbike accident, Dr Leatt set about working on a solution to avoid neck injuries that are all too common in bike sports. A few years later, Leatt the brand came to be, hitting the market with a neck brace. This revolutionary neck brace quickly became a global phenomenon and was soon adopted for mountain bike use.

In 2015, Leatt launched its first range of mountain bike helmets, and, by 2020, the band dove headlong into the MTB world, offering head-to-toe safety and gear solutions. Now in its 20th year, and with numerous design awards and industry accolades, Leatt recently began a new chapter here in New Zealand. With a new distributor now in place, we’re sure to see this storied brand continue going from strength to strength, becoming a more dominant player locally.

Trail 2.0 Shorts

As with jerseys, we’ve recently seen an influx of riding shorts that do the job but, much like my school report card said; “could do better”. The truth is, most of us are happy to stay in our lane and have no idea what we’re missing out on elsewhere, not keen to branch out from the norm and try a different brand of gear for fear of not liking it.

At first glance, I was unsure about everything going on with the Trail 2.0 shorts. “Is this overkill?” I thought to myself, looking at all the pockets and panelled fabric.

Sizing-wise, I’m a medium or 32” in any type of short and, true to form, the Leatt Trail 2.0 in the medium is spot on for me. With no tension on the hook & loop adjusters on each hip, they’re just right in the waist and, on the off chance I lose some weight, I’ll be able to cinch these up to keep the fit perfect. The length is a little longer than other trail-focused shorts in the market, but it sits nicely over the top of a kneepad and midway down my kneecaps.

The fit is somewhat slim and has a tailored, pre-curved silhouette to suit the riding position of the ‘trail’ riding they’re intended for. The mid-height crotch keeps it from snagging on the saddle, and a double dome snap closure and zipped fly keep the shorts in place and give critical access when needed. Two deep hip pockets ensure what you put in them stays in them, and a zippered cargo pocket on the right thigh has space for anything that won’t fit in the hip pockets. I’ve been surprised at how much I’ve put the extra storage to use, stashing food or a GoPro in there, which in the past would have either been left behind or crammed uncomfortably into a hip pocket. The pocket bags are attached to the outer fabric at their deepest point, keeping them in place so they don’t jump around while riding.

The fabric of these shorts is a lightweight polyester weave with 360° stretch, and most seams are double-row stitched for durability. Key wear areas around the knees and between the legs use a marginally heavier version for increased durability. A softer fabric is used on the inside of the waistband, ensuring comfort against the skin. The inside of each thigh has a small row of laser-cut ventilation, which helps keep things breezy.

The Trail 2.0 shorts come with a snap-in liner short. The main fabric is a mesh weave to keep things drafty, and there’s a nice silicon-backed gripper on the bottom of each leg. Many liners I’ve had supplied with shorts have ended up in the bin after a couple of rides, the chamois being of low quality and ultimately uncomfortable—often leaving me with some decent chafed patches on my undercarriage (don’t ask!). In a couple of cases, literal cuts in my buttocks from the chamois edge! Fortunately, that’s not the case with the Trail 2.0 shorts, which fit well. Even though I initially thought it might be too small, the Dual Density Berenis Chamois is comfortable for lengthy periods, and my undercarriage has no complaints.

What don’t I rate? Given the shape, pockets, and the two weights of fabric used across the short, there are a lot of seams. Granted, almost all of them are a double-row, reinforced type, so there’s probably nothing to be concerned about. However, more seams mean more possibility of one becoming damaged and potentially coming apart during a crash or due to long-term wear. So far, I haven’t seen any issues, but time will tell how the shorts hold up.

All in all, this is a banger pair of shorts. I’ve found the cut comfortable, the storage is excellent, and the liner gets a big tick of approval.

ReaFlex Hybrid UltraLite Knee Guards

Ever since a fateful day three years ago, I’ve worn knee pads of some description almost every time I’m on a bike. Late one afternoon, on a local trail I’d ridden a hundred times, probably more, my bike pitched over and fully committed to a corner. Halfway through the bend, the trail was freshly resurfaced with rotten rock and what was once a grippy turn I could blast through without a thought, was now a loose, jagged surface just waiting for some flesh. Unlucky for me, I was its victim. I had a nasty contaminant-filled gash in my knee, a scrub out at the hospital, a bunch of stitches followed by a few bags of IV antibiotics, and a few weeks off the bike in mid-summer, no less. I’d learned the lesson several times over the years, but this metaphorical straw broke the camel’s back and taught me once and for all. Knee pads are now a must-have on most rides.

The Reaflex Hybrid UltraLite Knee Guards are slip-on knee protection, focused on protecting while out for a pedal, rather than a heavier focus on pure gravity with less pedalling. The guards meet a CE impact certification of one out of a possible two, meaning more protective guards are available, but these do the job as advertised. On the Leatt safety scale, these reach a score of 12 of a possible 25, putting them in the middle of the Leatt range.

The main fabric through the front two thirds of the guards is lightweight (although not as light as some) and sock-like, with a good amount of perforation to aid airflow. The rear third of the guard is ‘AirMesh’, a moisture-wicking, lightweight mesh that helps with breathability. The top cuff features a non-slip silicone printed grip to help keep them in place.

The main padding is provided by ‘ReaFlex impact gel’. It’s soft and pliable while pedalling, and hardens under impact. The outer layer has knee cap and upper shin protection, helping to distribute impact and deflect and slide during a crash.

Although Leatt sells these as “super slim and lightweight”, they’re a fraction bulkier than other “super slim” offerings. Still, the difference in bulk and the gnat’s hair of extra weight is simply because these guards offer more protection than others in this “super slim” category. The ReaFlex impact gel wraps around the knee cap a tad more than some other lightweight guards, although the actual sides of the knee don’t get any padding aside from the sleeve fabric. You’d want to step up to the ReaFlex UltraLite PRO Knee Guards to get this extra side protection.

As with other Leatt products, subtle details make a noticeable difference in the function of these guards. In this case, above the calf is a soft, rubber-backed strip incorporated into the rear mesh. Not only does this offer an element of reinforcement to the lightweight mesh, but it effectively grips above the calf and helps lock the guards in place, not only due to the friction of the rubber, but it works as a ‘cuff’ that sits on top of the wearer’s calf. It works well, and you’ll never know it’s there, although you’d know the difference if it wasn’t.

The fit is comfortable and cosy, and the stretch of the fabric provides an even tension down the entirety of the guards. They breathe well, and I’d put them on par with other similar guards I’ve used. They are not exceptional, but certainly better than heavier weight, bulkier knee pads. Compared to my knobbly knees, I’ve got large calves and quads; even with my lumps and bumps, the guards are comfortable, and there is no pinching, bunching or tight spots while pedalling. My slightly abnormal leg shape (I jest) means the top cuff on all knee pads slides down a little while riding, eventually finding a spot lower down my thigh than I’d like; these ReaFlex’s are no different. They fit fine and work as they should but, like the rest, the cuff ends up lower than I’d like, and there’s no magic sauce to keep them where they should ideally be. My solution is to tuck the cuff of the guards under a liner short leg to keep everything in place.

With five sizes on offer, from small to double- extra-large, there should be a size to suit everyone. A quick measure-up and comparison to Leatt’s size chart gives prospective buyers confidence in their choice.

I rate the Hybrid UltraLite Knee Guards as a level up from most other lightweight offerings. The fit is spot-on and comfortable. There’s an excellent level of protection on offer, considering how light they are, and the outer shells add an extra element of protection that most lightweight guards don’t have.

Enduro 2.0 Convertible Helmet

Protecting your body begins at the top. If your head takes a bad enough impact, it doesn’t matter how unharmed the rest of you may be; without a functional brain, you’ll be on the sidelines while your buddies are out enjoying their rides. As concussion becomes a more widely talked about subject, and awareness is at an all-time high, people are taking more interest in what their helmet offers regarding protection. Rather than settling for something that passes a minimum safety standard, many of us are now looking for something that surpasses standards, offering the maximum protection, not just a sticker that says it’s safe enough. Never has there been a more important reason to invest in your head than if you’re riding an eMTB. With a bike that weighs over 20kg, and often up to 30kg, you sure want to ensure your head and face are well protected in case that big rig lands on you.

Full-face helmets have their place but don’t suit every scenario, trail system or ride. Enter the Leatt Enduro 2.0 convertible—a versatile helmet designed to cover all bases from cruisy rollers in open-face mode to gnarly steeps with the chin bar attached. The Enduro 2.0 is at home in most situations—it’s up to you how you dress it; chin bar on, or off.

The main helmet comprises a lightweight polymer shell with Leatt’s patented 360° Turbine Technology fitted (more on that in a bit). Securing the helmet firmly in place is a FidLock buckle and a classic ratcheted dial adjuster on the back, with three vertical positions to get the fit just right.

The 360° Turbine Technology is a crucial technology across Leatt’s helmet line. It’s a group of small disc-shaped rubber ‘turbines’ that twist and compress to decrease peak brain acceleration by up to a claimed 30% at impact speeds associated with concussion, and to reduce peak brain rotational acceleration by up to 40%.

The peak is adjustable and suits the overall styling of the helmet. There’s enough vertical adjustment to put it in the highest setting and have your goggles on your forehead for a climb if that’s how you roll. The visor will break away if you clip it on a low-hanging branch or during a rag-doll of a crash, popping off to save torsional forces being transmitted to your head and neck; safety first, safety second.

The shell has 20 vents to keep the draft flowing and, even at slow speeds, I’ve been impressed with how well it breathes. Strategically placed rear vents double as a sunglasses dock and do their job as they should.

The chin bar is simple to remove and refit with a button on either side just below the ears. Firmly press the button on each side and the chin bar releases. Reverse the process to re-fit it while ensuring the two locators up by the temples line up correctly, and Bob’s your uncle. The chin bar passes ASTM impact testing, offering confidence that it’s up to the task. It’s a sturdy system and is firm once in place, integrating exceptionally with the main helmet, offering some comfort that it will stay put in a crash and protect your face.

Putting the helmet on once the chin bar is in place is noisy. A lot of creaking comes from the junction between the helmet and the chin bar. Fortunately, once the helmet is on, the noise disappears, although it was pretty disconcerting the first time I put it on!

Given the extra engineering and structure required to incorporate the removal mechanism and chin bar safely, the Enduro 2.0 in open-face mode is a touch heavier than regular open-face helmets at 409g in a medium size. The chin bar itself doesn’t weigh much at all at 245g and, once fitted and in full-face mode, the helmet’s complete setup weighs 654g, putting it at the lighter end of convertible helmets.

The Enduro 2.0 is comfy on my head, and the padding is quite thick compared to similar helmets. There are no hard points anywhere, and the overall shell looks normal when worn; no giant mushroom here. Before wearing it, I thought the Turbines might touch my head while riding, but I haven’t noticed this. This helmet gets a big tick on the comfort front. As with anything fit-related, different head shapes suit different helmets, so I’d recommend trying before you buy or at least checking returns policies when purchasing online.

When it comes to testing the actual safety of the Enduro 2.0, alongside the legal safety standards they meet, I can only rely on Leatt’s testing and their force reduction claims; some heady statistics proved not only in Leatt’s research lab but also by people I’ve met who have firsthand experience with the safety of Leatt helmets.

I’d recommend the Leatt Enduro 2.0 convertible helmet to anyone doing all sorts of riding, perhaps travelling to unfamiliar areas to ride and not sure what to expect. You’ll have the right helmet for the task wherever you end up. If your riding crew decide to do a lengthy trail ride: Chin bar off and open-face mode. A last-minute decision to punch out shuttled laps? Chin bar on and full-face mode engaged. For eMTB riders, adding a chin bar is an absolute no-brainer, but there’s still the versatility to run the helmet without the chin bar for a cruisy lap with the kids or a nip to the shops.

Specialized Levo SL Comp Alloy

Words Lester Perry

Images Jamie Fox

RRP $11,500

Distributor Specialized NZ

The Specialized Turbo Levo SL debuted in 2020. With its discreetly integrated battery and motor system, it looked more “normal” than the competition’s eBikes at the time. The Levo SL set the standard for eMTB aesthetics and was a lighter, more agile alternative to the standard Turbo Levo, Specialized’s full-powered bike that launched five years earlier.

Now in its second generation, we’ve seen an evolution in suspension, updated geometry and improved motor efficiency. I’ve spent roughly two months with this bike, changing its many adjustments and razzing it around my local—and some not-so-local—trails.

Chassis

The SL2 Comp Alloy is the gateway into the SL lineup. With its alloy frame, it’s what I’d call the heavyweight of the SL range; the frame comes in at a kilo heavier than the carbon equivalent, so although there’s not a vast difference between the two, a kilo is a kilo. Considering the motor and battery are identical to those of its higher-end carbon brothers, the Comp Alloy would be an excellent platform for future upgrades; decreasing its weight (although not by a drastic amount) and adding to the overall ride experience with better components.

With a 160mm front suspension fork and 150mm travel in the rear, the Levo SL2 strikes a healthy balance of brawn and butterfly. There’s enough travel and the geometry is designed to not hold you back on the nastiest of descents, yet the bike is light and nimble enough to pick your way through tech, rapidly change direction, and even bunny hop or manual through sections with surprising ease.

This bike could be viewed as a couple of different bikes, able to be configured in a number of ways thanks to the breadth of adjustment available: the head angle is adjustable between 63 degrees (slack), 64 (stock), and 65 (steep). Adjusting this is almost as easy as replacing a headset bearing; remove the stem, headset top cap, compression ring and bearing, and lift out the upper headset cup. No tools are required. Drop in the supplied ‘adjustment’ headset cup; depending on its orientation, you’ll either get down to 63 degrees or up to 65.5 degrees. Refit the headset components—and job done. There’s no need to touch the lower headset cup at all.

The bike has a mullet wheel configuration, a 29-inch wheel up front, and a 25.7-inch out the back. Thanks to a flip chip on the Horst pivot (near the dropouts) that lengthens the chainstays by 10mm, the rear wheel can be swapped out for a 29-inch if you want more roll-over capability without nuking the machine’s handling. The bottom bracket is adjustable to a minor degree by flipping its off-centre lower shock mounting hardware and raising the bottom bracket by 5mm from stock. It’s a scant amount but will offer a smidge more clearance for the pedals and motor housing over technical terrain, although I haven’t found this to be needed in the stock ‘low’ setting. It’s worth noting that each adjustment made will affect all geometry numbers. Specialized have a chart in the manual explaining what the numbers look like with different adjustment configurations.

I toyed with the head angle a little, riding with it in the stock 64 degrees to begin with, then in the steeper 65 degree setting. The stock 64 degree setting was a good middle ground for most trails, although it felt a fraction slacker than ideal on flat or mellow trails. So, I fitted the adjuster cup, setting it to 65 degrees. The one-degree steeper head angle increased the manoeuvrability on anything mellow and tight, but it wasn’t as stable on choppy descents. I never felt the need to slacken the bike to 63 degrees, but if I were headed somewhere to ride steeper, faster trails, say Queenstown or Nelson, the slacker setting would be ideal. The stock 64 degrees seems to be the perfect middle ground for general riding.

Given all the adjustment options, this bike can adapt to optimally align with your riding style and the trails you ride.

Genie Shock

This latest iteration of the Levo SL features the Specialized developed, Fox-manufactured, Genie shock. This unit launched to fame on the latest Specialized Stumpjumper, claiming a coil-like feel and a tuneable mid- and end-stroke.

By making the main air spring larger, they’ve enabled the shock to maintain small bump sensitivity and relatively linear progressivity through the first 70% of its stroke. With 30% of the stroke remaining, the shock closes off most of the total air volume, essentially creating a smaller volume air spring active for the end of the stroke, causing a much steeper ramp-up and drastically increasing bottom-out resistance. On a bog standard air shock, in most cases (depending on the bike design), you sacrifice small to medium bump compliance and sensitivity to achieve decent bottom-out resistance, and vice versa. Bottom-outs increase once you soften the shock in a quest for buttery small bump and mid-stroke sensitivity. The Genie manages to deliver small bump sensitivity while maintaining super end- stroke ramp-up, and bottom-out resistance.

After my first ride on the Genie, I was amazed at how linear the shock felt, and it certainly delivered on the coil-like claims with a buttery smoothness. Although it performed well, I wanted a bit more support to push against while pumping and jumping, and felt it was moving through more travel than was necessary, causing it to wallow at times. Mid-stroke tuneability is in the shape of plastic volume bands fitted in the air can, much like many other shocks. They’re simple to fit and equally easy to remove. Let all the air out of the shock, pick off the snap ring that holds the air can on, slide it back, snap the two halves of a volume spacer together over the shock body, slide the air can back into place, refit the snap ring, air it up and hit the trails—all you need is a small pick—or in my case, a tiny screwdriver from my son’s tool kit that worked as one—a shock pump and five minutes.

Once I slid the air can off, there were no bands to be found, which explained the overly linear feel. I fitted three bands of a possible four, aired back up to 33% sag, and confirmed my choice with some front-yard testing. It wasn’t until I hit the trail that the extra support really brought the bike to life, increasing how playful and lively the bike was on the track.

The end-stroke is also tuneable by adding circular chips to the shock’s interior air chamber. It’s a slightly more involved procedure, but it can still be done without removing the shock from the bike. The end-stroke ramp up and bottom-out resistance was fine for me in its stock setup, so I didn’t change anything here.

Once dialled in, the shock performed like the literal magic carpet Specialized intended. Thanks to the Genie’s effectively softer-than- normal spring rate early in the stroke, the small bump sensitivity was impressive, and there’s an amazing amount of traction on offer, it’s really noticeable how well the rear wheel tracks across bumps while pushing through a rough section or corner, compared to many other bikes.

Spec highlights

Fork: Fox Float 36 Rhythm | grip damper 160mm travel. The fork is stout enough to handle the heft of the bike, and did an adequate job, but could benefit from better damping and adjustment. A worthy upgrade, or step up through the SL range to get these benefits. Brakes: SRAM Maven bronze | 200/200mm rotors. Mavens get the big tick from me, the power and consistency are amazing and they add a level of confidence to an eBike that I don’t think can be gained by any other single component. Drivetrain: SRAM GX eagle shifter, chain and cassette, coupled with a SRAM X01 derailleur. Does the job admirably. Once it eventually wears out, I’d replace this with a SRAM T-type system as it’s far superior on an eBike.

Crankset: SRAM S1000, 165mm length. Short cranks are the best on eBikes, and 165mm is a great choice.

Wheels: In-house Specialized alloy rimmed set. They do the trick but, considering that the bike had hardly any use when it turned up but the rear wheel already had a small flat spot in it, I’d say that much like many OEM specced alloy wheels, these rims are on the softer side.

Tyres: Front—Specialized Butcher | grid trail casing | gripton t9. Rear—Specialized eliminator | grid gravity casing | gripton t9/t7. No complaints here. Reality is that, with the extra weight of an eBike, most tyres perform pretty well. Good to see a heavier Gravity casing specced on the rear, although with their softer compounds, the square edges are worn from the knobs quite quickly.

Cockpit: We get some plain Jane—but effective—alloy parts here. The handlebar has 20mm rise and a comfortable shape—no real complaints, but an easy place to upgrade.

Seatpost: X-fusion manic 170mm. This post fits the price point well, there’s no noticeable play in the post and it’s nice and smooth, but the return is a bit slower than ideal.

Motor unit

At the heart of the Levo SL2 is the new SL 1.2 motor, Specialized’s latest—and a noticeable improvement on the previous SL 1.1 generation. It offers a quieter, more natural-feeling ride, delivering 50Nm of torque, up from 35Nm previously, with 320 watts of power. Although there’s enough power and torque to get you through most scenarios, the light weight comes with the feeling that the motor is not doing all the work, you’ve got to play your part too.

The SL2 has a 320Wh battery, and a 160Wh extender is available. The SL series bikes are lightweight in all aspects of the driveline, compared to the standard non-SL Turbo Levo models, which are powered by the Specialized 2.2 motor pushing 90Nm, with a 700Wh battery. The range extender can also be used on the full-powered bikes.

The burning question everyone has regarding eMTBs is; “how long does the battery last?” The answer inevitably is always; “it depends”. There are so many variables at play that it’s hard to compare even the same bike between riders, let alone different riders on different bikes. I’ll put a stake in the ground, though, and you can make some assumptions from there. Fully kitted, I’m pretty well bang on 80kgs, and my local trails are either up or down; there’s a minimal amount of flat ground, so I’m either climbing or descending.

The climbs are pretty steep, and there’s sporadic pedalling down most of the descents. On a ride where I used Turbo most of the time while climbing the gravel road climbs (some very steep) and Trail mode everywhere else, I can get 1:45 to two hours out of the battery. The variance in time is solely down to how hard I’m riding; a solid, fast pace, and I’m looking in the vicinity of 1:45, but a little less effort on the climbs and I can get to two hours. On the same ride, if I backed the assistance down and asked a bit more of my legs, 2.5 hours or three at a stretch, may be attainable. For rides made up predominantly of flat sections, if I stuck to Eco mode, I think I could hit the 3.5 hours Specialized claim is achievable. The truth is, though, I don’t want to ride like that, so I budget my rides at 1:45 hours ride time and go from there. Once the battery is down to 10% charge, the bike will slide into Eco mode to help you limp home.

The power delivery is very natural; there are no surprises or sudden accelerations, and the motor simply does what it should and multiplies your power with a smooth ‘acoustic bike’ feel. There is a slight lag when initially putting effort into it, and this took a little time to adjust to, but I soon adapted to it. The SL1.2 motor rewards a cadence of around 75-90rpm for those looking to get the most out of each pedal stroke, so if you’re one to rely on the torque of a motor to get up a pinch, rather than shifting to a lower gear—this bike’s not for you.

Mission Control App

I didn’t faff with the app too much; I just synced up my phone with the bike, pushed some assistance settings to ‘max’ and got stuck in. I wanted to ride this like a standard bike and not get bogged down with tweaking, tuning and apps. It’s nice to have the ability to fine-tune assistance levels simply, and if a user wanted to maximise battery efficiency, one could nerd out with the settings. Software updates for the bike are done via a connected app, no need for cables.

MasterMind TCU

An upgrade over the SL gen 1 is the use of the MasterMind TCU (Turbo Control Unit). The screen is seamlessly integrated into the top tube and comfortably readable at a glance. Modes and screens on the TCU are controlled via the simple-to-use handlebar remote. It’s a nice touch to be able to micro-adjust through assistance levels in 10% increments if you want to get specific assistance while out on the trail, rather than relying on the pre-programmed three settings.

The ride

The Levo SL2 is the first lightweight, low-powered eBike I’ve ridden. So, my observations are compared to full-powered eMTBs and regular old pedal bikes.

Taking the SL2 for its first ride, my immediate thought was; ‘damn, this actually handles like a normal bike!’ My main gripe with full power bikes in the past has been that they don’t suit my riding style, they’re fun in their own way, but their weight means they’re more like a cruise liner than a jet boat… and it’s a jet boat I want! Precise, nimble, manoeuvrable, responsive, confident and playful are the current acoustic bike marketing buzzwords, I guess. Unfortunately, most of these boxes can’t be ticked on a full- power, full-weight eBike – as mentioned, their characteristics align closer with the cruise liner.

Descending on the SL2 takes the best from an acoustic experience and couples it with the best from an eMTB. The SL2’s higher weight than a normal bike combined with its capable suspension gives insane stability and predictability while descending but, being lighter than a full-powered eBike, combined with its balanced geometry, means it’s drastically nimbler and more precise down a hill than its overweight brethren. The ability to change lines and unweight through sections really sets this lightweight bike apart.

The more I rode the SL2, the more I was amazed at how well it corners. I didn’t need to change any components or make any adjustments at all to make it perform; I just got on and rode. Even in its stock setup, it handles turns exceptionally. Balanced geometry is a piece of the turn- shredding puzzle, and so too is the lower centre of gravity of an eMTB, but the traction on offer sure makes a difference, too; part of this will be thanks to the weight of the bike (over an acoustic one), but the suspension is up to the task. The SL2 is a leap above any other eBike I’ve thrown a leg over in the cornering department, and it is better than some trail bikes I’ve reviewed.

Jumping on the SL2 is great, and surprisingly so. The weight is nice and balanced, and it is predictable taking off everything from lumps and bumps to larger, steeper lips.

The bike cruises along flat trails where there’s no need for high power similar to a full-fat one, just more nimbly and playfully, not weighed down by additional motor or battery heft.

Compared to high-powered eMTBs, the SL2 didn’t give me superpowers to tackle super steep climbs—you know, the ones where you can barely keep the front wheel on the ground, even with your weight right over the front. Instead, the SL2 meant I could make it further up super steep pitches than I would on a trail bike, before I ran out of steam but, unlike a full-powered bike, I definitely felt like I needed to use my own strength, rather than just chopping into Boost mode and have the bike ‘pull’ me up the hill.

Without the power, torque or battery capacity of a full-fat eMTB, the SL2 still takes some effort to ride, and I found I can still get a similar workout to a regular bike while riding it, just covering more ground and not blowing myself up to maintain higher speeds. Riding a full-powered eBike I find I’m still getting a decent cardio workout, and it’s quite normal to be sitting up at high heart rates for long periods, but most of the time (unless I’m sitting in Eco mode), it feels like there’s not much leg strength necessary. The SL2 hits a sweet spot and, thanks to coupling it to my Garmin, I could see my own power input and proof that I was pushing similar watts to a normal bike, just going faster for them.

The SL2 let me ride how I like to ride. It’s light enough to be playful, but hefty enough to offer the composure and stability only extra weight can give while descending. Until this bike, I wouldn’t have considered owning an eBike as my only mountain bike but, after a couple of months aboard the Levo SL2, I may have found the bike that would make me switch sides.

CamelBak H.A.W.G Pro 20

Words Lester Perry

Images Henry Jaine

RRP $299

Distributor Southern Approach

There’s a particular style of trip where bike bags strapped to your frame either aren’t suitable for the route you’re attempting or simply don’t provide enough capacity for the required gear.

When Kieran Bennett and I took on our ‘Starevall or Bust’ two-day mission in the summer of 2024, we had an Aeroe handlebar cradle and dry bag each. That was handy — but with the trail being steep and technical in many places, the option for a rear rack was off the cards, and frame bags would have had to be custom made for our full-suspension rigs (and even then, wouldn’t provide the capacity we needed). CamelBak’s range of Packs was the answer — in my case, the H.A.W.G Pro 20, while Kieran went with a similar, but smaller, MULE Pro 14.

The H.A.W.G pack is designed precisely with missions like ours in mind. Twenty litres capacity, supplied with a 3-litre bladder, and room for another if needed. I opted for a single 3L bladder and a water filter, which, if you’ve read the trip report, you’ll know was a necessity!

Stowage is split into three main areas; nearest to the body is the hydration bladder sleeve. Outside of this, another large ‘full’ pocket features two large internal pockets, one of which is designed to hold a spare eBike battery if you’re that way inclined. In this section, there was enough capacity for me to stow a dry Merino top, a pair of shorts and a couple of freeze-dried meals. A smaller zipped pocket is on the left side of the back panel, down near the waist belt, although I didn’t use it on our trip. It would be ideal for smaller bits you may need to take with you but do not necessarily need easy access to — for example, a wallet or passport.

The next layer out has a medium-sized pocket featuring a couple of smaller zipped mesh pockets to store little items — in my case, tools and spares behind the zips, and some snacks in the main compartment. Across the top, there’s a fleece-lined pocket that is ideal for stowing glasses – and is large enough for goggles.

The outside of the pack features a stretch compartment, ideal for items that you might need quick access to — in my case, a jacket and bag of trail mix, and a First Aid Kit that we fortunately never required. The clips on either side have small hooks to clip helmet straps to for carrying.

Weight is supported on the hips with a sturdy waist belt and, handily, there’s a zipped pocket on each side for quick access to gear when you don’t want to remove the pack to access. There’s a good amount of room in these pockets. I stashed a disposable camera on the left side for quick access and, on the right, I had some lollies, a multi-tool and a tyre plugger.

The H.A.W.G Pro is the first pack I’ve used with the Air Support Pro Back Panel — a 3D mesh back and harness that supports the bulk of the pack, holding it away from your body as much as is feasible, allowing for maximal airflow between the wearer and the pack. Although it’s still noticeably warmer than no pack, thanks to the Air Support back panel, it feels much cooler than some smaller, more traditional packs I’ve used. The back panel provides a level of rigidity to the whole system and, combined with the harness setup (including the sternum strap), secures the entire pack nicely. It’s well supported, even while fully loaded and tackling rough terrain. Thanks to the secure fit and rigidity, the top of the pack works well for resting the bike on while carrying over hike-a-bike sections — something we spent hours doing while hiking up Mt Starveall.

Two straps wrap around the base of the pack and, once cinched down, they help compress the load, helping keep everything in place; handily, they’re long enough to strap on more gear. In my case, I secured my Thermarest Sleeping Mat to the base and saved valuable volume in the pack itself. There’s myriad uses for these simple straps: tent poles, rolled-up jackets, or (most importantly) baguettes — the possibilities are endless.

The pack is supplied with a snazzy little tool roll and, while it’s great in theory, I found I couldn’t get my preferred selection of tools and bits to play nicely with it. The tool roll stayed home while on the Starveall mission, and I brought my small tool bag along.

As far as hydration goes, I can’t fault the 3-litre ‘Crux’ bladder. Although I’m not a super fan of the huge screw top, it does the trick and is long forgotten once it’s tucked safely into the pack. CamelBak redeemed themselves with their market-leading (in my opinion) bite valve and “magnetic tube trap” that keeps the drinking hose nicely secure when not in use, and snaps easily back into place.

The only niggle I’ve found with the H.A.W.G is on the outer stretch compartment. The clips that secure each side and help compress the load are not a traditional bag clip design, I assume, to allow for the helmet hooks. More than once, I had issues getting the clip to close correctly on my first attempt; unless the clips are aligned perfectly, one side can stick out and not be clicked into place correctly. This led to the clips popping open a few times on our trip. It’s annoying but not the end of the world. With some attention, they work fine and are secure when clipped correctly.

When all’s said and done, I’m a big fan of the CamelBak H.A.W.G and its versatility. It’s large enough for an overnighter, and once cinched down, it’s compact and lightweight enough for just a few hours in the backcountry without feeling like you’re carrying a flappy, half empty pack.

Inno Tire Hold HD Rack

Words & Images Cameron Mackenzie

RRP $1249

Distributor Racks NZ

The concept of a platform bike rack is nothing new, with many of today’s mainstay manufacturers producing several different models each.

Whilst common, there’s seems to be a new brand on the block every other month, each offering a bigger, beefier and “better” option than the other guy – and Inno’s no exception. Up until recently, Inno is a brand I’d not heard of, let alone knew was available in the local market, but I quickly took notice when I stumbled upon their latest Tire Hold HD rack, offering what looked to be a significantly sturdier rack than anything else I’d seen thus far.

Bike racks have been a pain point of mine over the last few years – never seeming to get more than two years out of a Yakima rack before it bends, breaks and/or rusts past the point of safe use. Whilst the way I use it – leaving it attached to the back of my truck year-round and lapping the country in search of the perfect MTB photo – may be a hard life for a rack, they’re a tool, and I expect more. I mean, who has the time or strength to be lifting their 25+kg rack on and off the car and into the garage for storage between weekend Woodhill trips?

Inno’s latest offering, the Tire Hold HD rack, steps things up, offering large weight carrying capabilities, a wide range of tyre size compatibility, and a design that removes any frame contact – one which, up until 2015, was unavailable on a rack outside of the US.

Fitting Inno’s rack onto my truck was a relatively straightforward affair, although, it did require a few small mods to make it all play nice. The rack features a little depth stopper that helps hold the hitch in the same place – presumably for easy alignment as you take it in and out – which I had to remove in order to get the pin holes to align. Their locking pin has a moulded plastic handle, but is of such a size that it prevented it from being able to be threaded in. Removing the plastic handle from the bolt (albeit forcefully) sorted the problem, and it now threads in easily utilising the 8mm hex key head.

As my bike quiver has evolved, so too have my requirements for a bike rack, so the idea of a rack built largely out of aluminium, with the ability to carry up to 34kgs per bike, hold strong and handle off-road use held big appeal.

The strength of the rack is clear when looking at the size of the hardware and pivots featured throughout. The main pivot, which allows the rack to fold, features no-play and is actuated by a smooth and easily accessed grab-handle at the further-most end of the rack. Whilst elements of the plastic components used throughout make me a little nervous, the cowling encasing the main pivot is a welcome sight, helping to keep a lot of the nasty road grime and dust away from one of the key parts of this system.

Loading bikes is where this system shines. With the way in which the ratcheting arms work, the arms stay put once extended, allowing for one arm to be set in position, a bike rolled or placed up against said arm, and the last arm folded up and tensioned using one hand.

Unloading requires a little more coordination and the use of both hands. I find you need to pull the arm back towards the centre of your bike to take the pressure off of the ratchet, and have your other hand depress the release switch on the tray. My only gripe with this is that the ratchet mechanism requires you to keep the level pressed in whilst you slide the arm back, at times leading to you ending up in some creative body positions.

The tyre holders/arms feature a hard-plastic cup which acts as the key point of contact against the tyres and needs to be adjusted depending on the size of your wheels. Doing so is straightforward, but isn’t something you’d want to be doing each time you load your bike. As in our case, if you have a mullet-wheeled bike, or ‘his and hers’ with varying wheel sizes, you find yourself placing the bikes on the rack in the same order and orientation each time to avoid any hassle.

Each carrier bolts onto the main arm of the rack using a t-track style system (similar to what you’d find on roof rack type bike carriers), which allows for close to 30cm of fore-aft adjustment. This range of movement in pairing with the ability to place your bike anywhere on the carrier and adjust the balance of the arms to affect its position means the days of bikes mating is all but over.

Where other racks would creak and rattle, Inno’s HD rack hasn’t made a peep. Even with 45kgs of carbon and lithium swinging off the back down rough, corrugated gravel roads and mild 4×4 tracks, the bikes held rock solid and would barely wobble even, as the truck bounced around. Long journeys are much the same – hassle free and without movement.

The Tire Hold HD is designed exclusively around a 2-Inch hitch, so for those using a smaller hitch receiver or a tow ball, you’re out of luck when it comes to running this heavy-duty bit of kit. Inno offer similar models using a lot of the same materials and construction, but only for those whose vehicles don either a 1-1/4” or 2” hitch. For the towballer’s, sadly you’ll be needing to look elsewhere for the time being.

The ability to lock your bikes onto your rack is a feature you tend not to utilise all that often, but is one which you want to be well thought out and reliable when you need it. Unfortunately for the Tire Hold HD rack, the locking solution is the one feature which really lets it down. Their solution to security is a basic double-loop cable which requires being fed through itself on one end, and the other being clamped down by the hitch’s expanding wedge handle. The cable itself is something out of a primary school bike rack and wouldn’t take much to cut through or pull out of the locked handle. With the bike rack loaded, locking the cable in place would require you reach underneath the rack and fiddle around with a small key, realigning the handle on a small spline, and clamping said cable loop in place.

An easy solution would be to buy an aftermarket bike-lock and chain the bikes together, but for $1249, you’d hope they could come up with a better solution – perhaps wheels locks like the ones found on the Rocky Mounts or 1Up models.

My only other peeve of Inno’s rack is the inability to expand the carrying capacity after the fact. The Tire Hold HD is available in a two or four bike model, but neither option can be changed with the purchase or removal of an extension. Having that ability is helpful both ways – being able to shorten it for around town when it’s just you, or being able to take a car full of friends on riding trips, without the need to have two racks sitting in the garage.

Time will tell how well the Inno rack lasts but, for now, I’ll be keeping this one fitted, at least until I need to carry more than two bikes – and will be carrying my own lock.

CamelBak M.U.L.E Pro 14

Words Liam Friary

Images Henry Jaine

RRP $279

Distributor Southern Approach

I’m always scheming or planning an overnight trip, particularly during that time between the clocks springing forward and winding back again (boooo!). How much gear we actually need on a trip, and what we are going to use to carry it, is always a big consideration.

I don’t mind having some weight on my bike, but I always like to try and keep it free to move, so having a decent backpack with enough storage is an absolute must. Extra hydration is also key when pedaling off into the backcountry for hours and days at a time, making a reservoir a must have. For these trips you need to pack ya meals, snacks, layers, jackets, power bank and locator beacon at the very least, along with other essentials.

The M.U.L.E Pro 14 is aimed at big days out and comes with loads of genuinely useful storage arrays. The back panel is most excellently called ‘Air Support’ and really does help reduce sweaty back syndrome. It also features the brilliant Crux Reservoir which holds three litres of water. As well as a compartmentalised main storage chamber, the M.U.L.E. Pro 14 has a hip belt with cargo carrying capability (another must) and a removable bike tool organiser wrap thingy. You can also insert optional ‘Impact Protector’ spine protection armour into the pack.

When loaded up and out on the trail, the CamelBak M.U.L.E. Pro 14 isn’t that noticeable — and that’s a good thing! For a very spacious pack, it’s just so damn comfy – no pesky annoyances. The combo of stability and security is adequate without having to wrench the bag around my torso. My overnighter stuff was all packed into the CamelBak M.U.L.E Pro without hassle and if you need to pack a sleeping bag you can do that, thanks to two straps that have little hooks on them; I used these to secure my sleeping bag to the bottom of it. Again, when riding, the bag felt snug and secure — I could feel its weight, but it was well distributed. All contact points for the bag have been carefully considered, with each strap being made up of a cross-hatched mesh, along with a sponge centre for maximum ventilation. The traditional shoulder straps have a runner system for easy adjustment of the chest strap too, which reduces that cutting sensation on the armpits which can be a bloody nuisance with an ill-fitting and heavy backpack.

The M.U.L.E Pro 14 hosts a very spacious 3L bladder suitable for whatever your trail adventure. The reservoir is easily accessible via a full-length zip down one side of the bag — the bladder can be removed and refilled with ease, thanks to its helpful handle design and large opening towards the top. The quick release hose connection reduces faff in feeding it in and is great for cleaning as well. The drinking tube has a magnet on it, so it stays secure while you ride. I think the magnet is great for making a solid connection but, when riding and moving, you need to twist it – which can be a touch difficult.

Overall, the light open mesh absolutely lets the back breath whilst remaining secure. The hip straps and lumbar pad really help distribute the weight nicely. A handy addition is the mesh pocket on either side – big enough for a multi tool or snacks for quick and easy access. The best pocket, though, is the sneaky one on the left-hand side of the pack where the waist strap meets the bag. This little pocket is well protected and will fit your cell phone for snapping memorable moments. It meets all my requirements for storage space and stows enough water. The comfort reigns supreme and it does its job very well. Now, I just have to find some more time for backcountry missions?!

Trek Top Fuel

Words Liam Friary

Images Cameron Mackenzie

RRP$15,499

Distributor Trek New Zealand

The lines are somewhat blurred between an XC long-travel bike and a lightweight trail bike but, regardless of categorisation, the bike is designed to be super-adjustable with a redesigned frame and a 4-position Mino Link. There’s also a ton more you can customise, like wheel size, geometry, and suspension travel, making it super appealing for everyday trail riding, or even XC racing duties.

Trek has opted for refinement rather than revision – a trend the industry is increasingly embracing. Generally, bikes are in a good place regarding geometry numbers, so there’s no need to reinvent the wheel – at least for now. While the new Top Fuel looks similar to the previous generation, it has gone on a slight diet with about a 100g savings in the carbon frame, and employing slimmed-down tubes across the entire frame. The new 4-position flip chip, used for adjusting the bike’s geometry or the amount of shock progression, is located at the lower shock mount. This flip chip offers High/Low geometry settings that modify the angles by 0.5° and change the BB height by 6mm. Additionally, you can move the suspension leverage rate forward and backward with the flip chip. The forward position offers 14% progression, while the rear position offers 19%, providing more ramp-up at the end of stroke. I rode mainly with the rear, more progressive position and found it better suited to my riding style and the terrain where testing was done.

I appreciate the ability to change out the rear and front travel if desired. The rear shock is built around a 185x50mm shock, but you can increase the stroke to 55mm and boost travel to 130mm. The frame is rated for a 120-140mm travel fork, which allows for different setup options, such as an XC whippet with 120/120mm travel or a rowdier trail bike with 140/130mm travel. I’m inclined to build the latter so, hopefully, I’ll have more on that sometime soon. If you wanted to have a mullet setup with a 27.5” rear wheel, that’s also possible with this new platform.

Returning to small refinements, the new Top Fuel is slightly more progressive than the previous generation and has a tad more anti-squat. Rear travel is kept at 120mm and comes with a 130mm travel fork up front. 29” wheels are standard on all frames except the small, which is built around 27.5” wheels. The internal storage has also been updated with larger openings and better weatherproof sealing, and cables have been kept out of the way to minimise snagging. Trek has won the applause of shop mechanics by keeping cables out of the headset and eliminating the Knock Block headset. A tried-and-true threaded BB is used, as well as bolt-on downtube armour and a rubber chainstay protector.

While there are slight changes to geometry, the 65.5° head angle remains consistent across all sizes. The effective seat tube angle ranges from 75.2-76.9°; Trek lists this angle based on a specific saddle height for each size. Another update is the size-specific rear centre lengths, which vary from 435mm (smaller frames) to 445mm (X-Large frames).

I had the pleasure of riding the new Top Fuel in Durango, Colorado, USA. Having more than a week based in Durango meant I could get very familiar with the bike, logging over fifteen hours of ride time. There’s plenty of pedalling needed in Durango, and often you’re either riding long climbs, flats and descents that have pedal sections. I thought this bike was well suited to the terrain. The first thing that struck me was the pedalling efficiency and overall zippiness of the bike. I rode twice a day locally and had two high-country long ride missions as well. On all occasions, from road to gravel to trail, I didn’t feel the need to hit the lockout lever, as it pedalled great with it wide open. The bike feels swift and light and climbs exceptionally well.

The Top Fuel’s adaptability is the new four- position Mino Link at the lower shock mount. Effectively, this set of flip chips allows riders to choose between permutations of high and low geometry, and more linear or more progressive suspension curves. Initially, for the first few days of riding around the mountain bike parks of Durango, I had the Top Fuel’s flip chip in its default ‘low, less progressive’ setting. As we headed for longer high-country rides, a simple flip of the chip meant I could steepen the head tube angle by .4° and raise the BB by 6mm. I found this setting was ideal for ramping-up. It offered adequate dampening and felt comfortable even after several hours in the saddle. The more progressive setting reigned supreme across rowdier terrain on the longer descents in Colorado’s high- country. The bike moves very swiftly, especially over long rides. I’m a big fan of the flip chip!

While the RockShox Pike fork nods to more trail-oriented riding, there’s something about the overall frame that makes it more compliant than the white paper stats indicate. This compliance was evident when we ventured into the backcountry, which made for lengthy and rowdy descents. These rides were often long – around three hours or more – so having a compliant frame was welcomed. These rowdy sections are when the bike feels burlier than presumed. Again, on descents, the Top Fuel chassis is bloody solid; with the bike’s light weight, this is a little surprising. But, when you throw that together with the progressive rear kinematics, it’s confidence inspiring. Bear in mind, when things get really real – rough and steep and you need to pick your line – apply a bit more effort to stay cantered and weight both axles. That said, the newly designed compliance of the frame and separate linkages means smoother, grippy moments when it matters most.

On the shorter, punchier rides in and around Durango’s extensive trail network, the bike was super smooth and sprightly. Heck, simply making your way to the trailhead, the Top Fuel is just as sharp – sprinting forward eagerly as soon as you put the slightest pressure on the pedals. Uphill, it’s just as powerful and lively. From more XC-oriented loops to bike park-style jumps and berms to rock slabs, with sketchy rocky descents, the rear end stays active, even under brake load. I think the key component is the four-bar suspension platform over a single- pivot flex-stay, which offers superior grip both uphill and downhill. There’s suitable snappiness, and the bike generates speed very well.

Standing is fine but, for seated climbing, the Top Fuel is a beast. It soaks up big roots and rocks without losing traction or bouncing you offline. On rockier technical climbs I would normally not make it, but it would clear them. Although it’s not technically an XC race focussed rig, the Top Fuel is a super capable climber. And, with it being so well balanced, you can pick your way through more technical sections without having to carry a lot of momentum in. Cornering aboard this rig is bloody fun too. Leaning into flatter corners and railing berms is awesome. The balanced ride pays off here – keeping an ideal amount of weight on both wheels which keeps it easy to judge traction.

The Bontrager Line Pro 30 OCLV Mountain Carbon wheels do a great job. They’re sprightly and engage swiftly. These wheels are laced with Bontrager Gunnison up front and Bontrager Montrose out back – these tyres keep in fitting with the bike’s lightweight theme. I found them super supple and quite zippy but, on gnarlier rockier sections, I had to choose my line. Whilst they didn’t give me any grief on rockier descents, choosing the best line was imperative, as I was a tad worried about snagging them. I can understand the thinking behind choosing to spec these tyres, but if the bike remained with me, I’d prefer something a little beefier – even with the weight penalty. In saying that, they did hook up well – and impressed me on faster rolling sections. I suppose it really depends on your application for this trail bike, as it’s up for wide interpretation.

Keeping with the parts and component’s theme – the RSL MTB Handlebar and Stem comes equipped on the Top Fuel. On trail, I found the RSL handlebar/stem combo to be quite comfortable. It wasn’t overly stiff nor super compliant; it sat in the middle somewhere, which was kind of great as meant I could focus on the ride. I quite liked the RSL bar’s good feel, with enough damping to keep your hands from taking too much abuse. It provided reasonable comfort and was plenty stiff when accelerating out-of-the-saddle. The sweep and rise were dialled for me, as I usually run a slightly forward roll on my bar, but it won’t suit everyone. Although I do love the super tidy aesthetics and feel of the Bontrager RSL integrated bar and stem, I do think perhaps a more traditional bar/stem combo would possibly suit more riders. As the rest of the bike has quite a lot of adjustability, it would be good to have the same within the cockpit. Such as swap a shorter stem for gravity focused days and a longer one for long ride days or racing.

SRAM’s XO Transmission does a flawless job of shifting. I did break the chain, however, and luckily we had another chain-link with us in the backcountry. But that can happen at any time, to any groupset. I have XO Transmission on my personal bike and it’s super robust, shifts flawlessly and you never have to faff with it! I think if you’re spending your hard-earned cash on a new bike, then having Transmission is definitely worth your consideration. SRAM Level Silver four- piston brakes, with 180mm HS2 rotors front and rear are on stopping duties. I did find these brakes fairly good for some of the riding, mainly around the mountain bike parks of Durango with shorter descents. However, on longer descents in the backcountry they weren’t powerful enough. Keep in mind, that was mainly on super long runs with chunder sections throughout. I have been riding SRAM Maven’s on my personal bike, so am a bit partial to a heavy hitting brake. Again, if the bike was mine, I would upgrade to a bigger front rotor and possibly swap these brakes to SRAM Codes.

This bike is bloody fun! Hands down one of the best bikes I’ve ridden this year. It’s sprightly but super capable. The balanced ride inspires a ton of confidence. It pedals everywhere super efficiently – dances uphill, generates speed across flats and shreds going down. Its more bike than you think and makes a strong case for having a shorter travel bike! Of course, there’s a few nit bits that could be addressed as I’ve mentioned but, overall, the new Top Fuel is all class. I’m very keen to build this bike as a burlier 140/130mm trail bike, so hopefully we can make that happen soon.

Commencal Meta V5

Words Lester Perry

Images Bevan Cowan

RRP $10,000

Distributor Commencal New Zealand

Since its creation in the year 2000, Commencal has been a mainstay in the downhill racing scene. Max Commencal, the BMIC (Big Man In Charge), enjoyed earlier success with SUNN Bicycles, a BMX company he formed in 1984. By the early 90’s, SUNN shifted its focus to Downhill MTB racing.

Beneath names like Nicolas Vouilloz, Anne- Caroline Chausson, Cedric Gracia, and other greats, the SUNN Downhill team amassed multiple world titles aboard their innovative downhill bikes.

Under the Commencal brand, their riders remain some of the sport’s winningest to this day; at any World Cup Downhill, across all categories, you’ll likely see a Commencal rider on the podium. This hunger for competition drives the development and direction of the now global, direct-to-consumer brand. The Meta V5 is a product of their Commencal Enduro Project and the four years of development under team riders that preceded its launch.

Development

Applying the same development theory and methods that brought downhill success, the Meta V5 was created to be Commencal’s comprehensive Enduro Race bike. Commencal aimed to provide their racers with one platform that would excel across all scenarios they’re presented with over an Enduro World Cup season. Alex Rudeau proved their development process was on point, securing himself five podium finishes and third overall in the 2023 Enduro World Series. The proof is in the pudding.

Frameset

Keeping with Commencal tradition, the frame is 100% alloy like the rest of their range—not a carbon fibre in sight. Rolling on 29er wheels, with 150mm rear travel and 160mm up front, this bike strikes the sweet spot of travel vs. pedalling ability and agility. Carrying speed is key to Enduro and the V5 delivers.

An alloy frame would be a prime candidate for a threaded bottom bracket but, for whatever reason, Commencal has stuck with a bb92 press- fit style. In fairness, I’d rather have a press-fit in an alloy frame than a carbon one, so I guess they’ve landed in a bit of a middle ground on the V5.

The frame features a plethora of tubing profiles; there is not a single ‘regular’ round tube anywhere. Depending on location, each tube is shaped to achieve specific strength, weight and compliance. Under the top tube is an accessory mount, and there’s a bottle cage mount situated in a small channel indented in the downtube tube. As is customary on most bikes today, a UDH hanger graces the dropouts.

The front and rear triangles connect with a series of bolts, bearings, and pivots that make up the VCS (Virtual Contact System) linkage. Ten bearings are spread through the swingarm’s five pivot points. The swingarm has some smart subtleties: bearing caps help keep grime out and expander plugs in the pivot axles help keep them tight. The lower end of the shock features a flip chip, allowing for a small amount of geometry customisation.

Let’s get through the details before looking at my thoughts after a couple of months aboard the V5:

Geometry

Although nothing jumps out as too progressive or outside the realms of sensibility when looking over the geometry chart for the Meta V5, there’s a lot to like. There’s a flip chip on the lower end of the rear shock, and other than a cursory couple of rides in ‘High’ to confirm there’s no massive difference between the two settings. I’ve stuck with the bike in ‘Low’, as I’d imagine most riders would do.

There’s nothing crazy here; I’d point out a middle-ground head angle and reasonably steep seat tube angle. As is becoming customary with Commencal’s bikes, the stack height is above average and pretty big for a medium-sized frame, a trend that seems to be taking hold with some brands.

The Ride:

According to the Commencal size chart, at 176cm tall, I sit right at the top of the Medium recommendation and at the bottom of the Large. With a bike of this ilk and travel category, I chose to go smaller rather than larger, and settled on the Medium size.

A couple of weeks after exchanging a emails with Commencal about how and where I ride, how long I’ve been riding, and what sort of rider I consider myself to be, a pre-tuned Meta V5 arrived on my doorstep. Frothing to get out, I quickly mounted the handlebars in the stem, attached the front wheel, and was good to go; the assembly only took about five minutes, including removing the bike from the box. A quick driveway test confirmed the supplied setup felt like it was in the ballpark of where I’d like it to be; they’d even trimmed the bars to my preferred 760mm width — bonus.

To give my thoughts some context, compared to my usual ride, this bike comes in at 10mm less travel on either end, a 14mm shorter reach, a 10mm higher stack, a 2-degree steeper seat tube, and almost equal chainstay length and head angles. Considering the 30mm riser bar, my hands end up roughly 30mm higher than my bike – quite a lot. Weight-wise, the Commencal comes in a little heavier, but not by an amount that makes a difference to anything; it adds to the feeling of stability. Considering how similar the geometry is between my bike and the Meta V5, they’re poles apart in how they ride.

I get on some bikes, and everything clicks immediately; this was one of them. Although I initially felt the shorter reach and higher front end compared to my bike, I quickly forgot these differences and was comfy on the bike after just a couple of runs down a trail. Not once have I felt like I wasn’t in the correct position on the bike or had to shift to a particular body position to get the bike to do what I wanted; everything just seems to click nicely, and now has me questioning my usual setup.

The suspension settings, as supplied, 71 psi in the fork and 177 in the shock, were ideal for getting to grips with the bike; nice and balanced, with no surprises. A couple of rides in, as I got used to the bike and speeds increased, I added a little air pressure front and rear and, taking this into account, slowed the rebound and added a click of compression damping to both front and rear. The Meta V5 is a full-gas Enduro bike and, although optimised for descending, you still have to make it to the top of a hill before heading back down. The Meta V5 is not a spritely climber, but it gets there. Out of the saddle, while under power, the suspension firms up substantially and gives an excellent platform to push against, i.e. when tackling steep technical climbs or sprinting over a punchy climb, it does both well. When I’m ticking my way up a gravel road or a long, smooth single-track climb, I’m immediately reaching for the lockout on the shock; the firm pedalling platform and steep seat tube make the climbing position comfortable and efficient.

Descending is a dream, highlighting some savvy design and an equally impressive suspension package. The VCS linkage is a virtual pivot linkage offering super plush suspension that’s supple off the top, offering wicked levels of grip; through the mid-stroke, it feels pretty linear but still has a good level of support. Even though it has 150mm of rear travel, it feels more over big hits or flat drops as it firms right up at the end of the stroke, preventing any harsh bottom outs, and I can’t think of a time when I’ve actually felt an abrupt end of the travel.

With all the links and pivots involved in the VCS, the rear end of the bike is quite wide to accommodate it all. It’s so wide, in fact, that it’s quite normal to drag my legs on it while riding. Not to the point of being annoying, but it’s noticeable and will inevitably rub and mark the frame over time. Fortunately, the bike I received has a tidy ride-wrap installed, so the paint isn’t affected.

I find the front end stiffer than many bikes, and the suspension works in combination with this front-end rigidity and the flex of the back end to provide a ride that’s quite unique, but only in good ways. While charging through rough sections, the bike remains composed with amazing stability and with no harshness or the feeling of being deflected off obstacles or ‘pinged’ off square edges. The chassis floats across the chunder, reacting more to rider input than the trail feedback. Thanks to this, I felt less fatigue on long descents, feeling there was no need to wrestle the bike to stay on line or keep it where I wanted, I could just stand centred on the bike and let it do the work.

Considering the weight, travel and reasonably linear mid-stroke suspension kinematics, the Meta is surprisingly lively and is fun to pop off trail features and manual through sections; even though it’s such a sled, it strikes a surprising balance of high-speed downhill capability and mellow trail cornering agility and playfulness.

The overall balanced feel lends itself to aggressive and controlled cornering. Initiating turns or quickly changing direction is simple, not requiring any dramatic weight shifts to maintain traction.

Adding to the predictability and stability is some well-engineered flex in the back end, that works in harmony with the suspension. Much like the Cannondale Habit LT I reviewed a few months back, there’s an amount of lateral flex in the swingarm. Still, tuned compliance has significant advantages, particularly at this mid-travel level. It helps keep the bike composed in the rough and gets across off-camber more smoothly by assisting the wheel to stay on the ground rather than being deflected off bumps (where stiffer bikes would rely more heavily on just the suspension to move the wheel). I’m not sure this trait is necessarily faster in itself, but the resulting reduction in fatigue over the long run is certainly noticeable.

One thing that struck me early on was how quiet the bike is. Thanks to substantial chainstay and seat stay bumpers and tidy cable routing, the bike maintains a nice, dull sound when on the trails. By the look of those bumpers, the chain is still hitting them while slapping around, but they’re doing their job well and keeping sounds muted.

On my second ride, the frame developed the dreaded and much-publicised creaking in one of the pivots. Considering the bike had a pre- review strip down and grease, this was quite a surprise. Thankfully, after going through the involved process of getting to each pivot bolt and re-tightening them (it’s a total faff to do), the creak faded out. It seems the pivots will need some attention every 4-6 weeks, depending on the conditions they’re ridden in. I’ve had similar experiences on other alloy bikes in the past, and it seems to be part and parcel of alloy frames; when compared to a carbon frame, a bit more care and attention are necessary to keep pivots clean, tight, and creak-free, this Commencal is no different.

I’m not a fan of the Fidlock drink bottle that was supplied. Unfortunately, without customising a bottle cage, there’s no way to carry another bottle style in the front triangle. It’s much fiddlier than a standard bottle to put back in its holster after a sip. The saddle isn’t terrible, but it’s on the firmer end of the scale and, after a couple of hours pedalling up hills, it doesn’t agree with my backside; it may be my preference, but I’d like something a bit softer.

Like many others, the Commencal product managers missed a beat when it comes to the dropper post. At 175mm, it’s not the shortest drop around but, even with my 720mm seat height, a 200mm post would fit. Adjustable dropper posts are available, and I’d love to see one on this bike to maximise the drop and allow riders to fine-tune it to their needs.