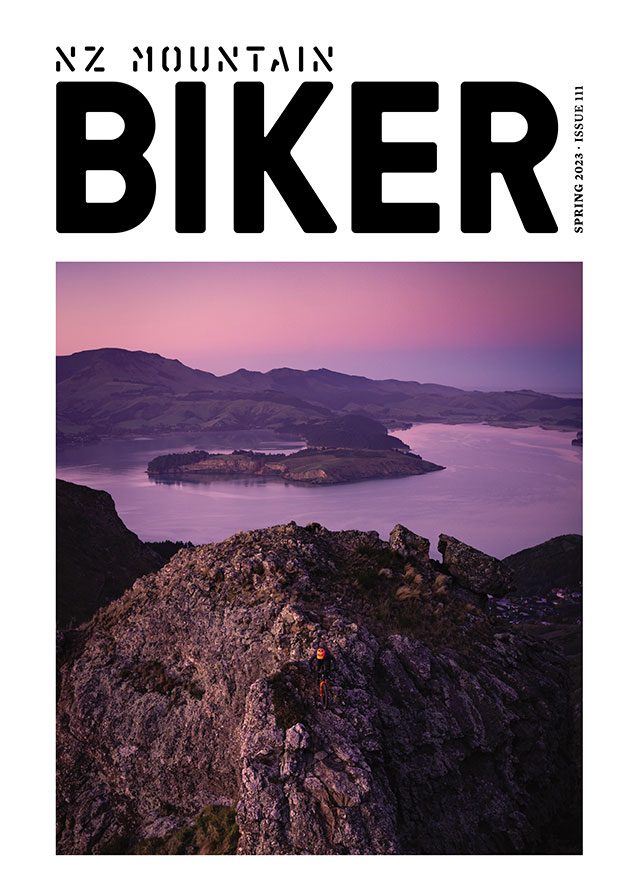

Las Cholitas

Words: Jess Dickinson

Photography: Keenan DesPlanques

We picked a line and dodged our way down to our day one camp and a hot meal from Rocky, our gold-toothed cook. An altitude-induced throbbing head and uneasy stomach had come with me to camp, so I took myself away to sleep off the little voice inside that said I shouldn’t be up there.

The Little Idea

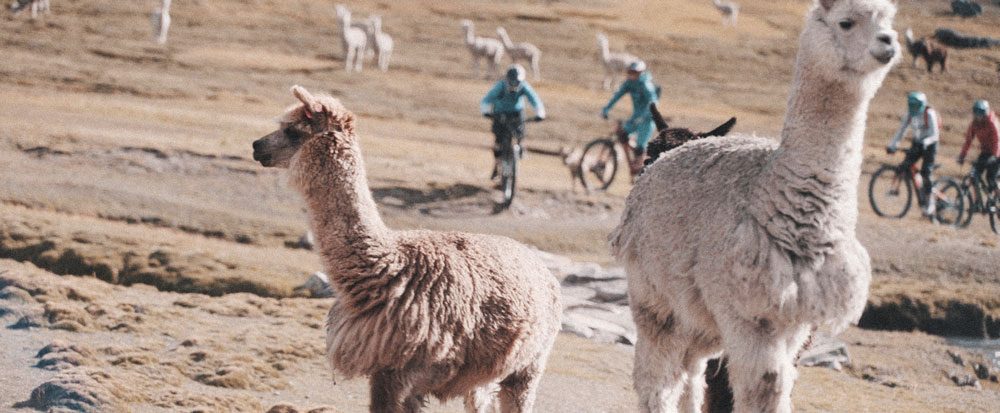

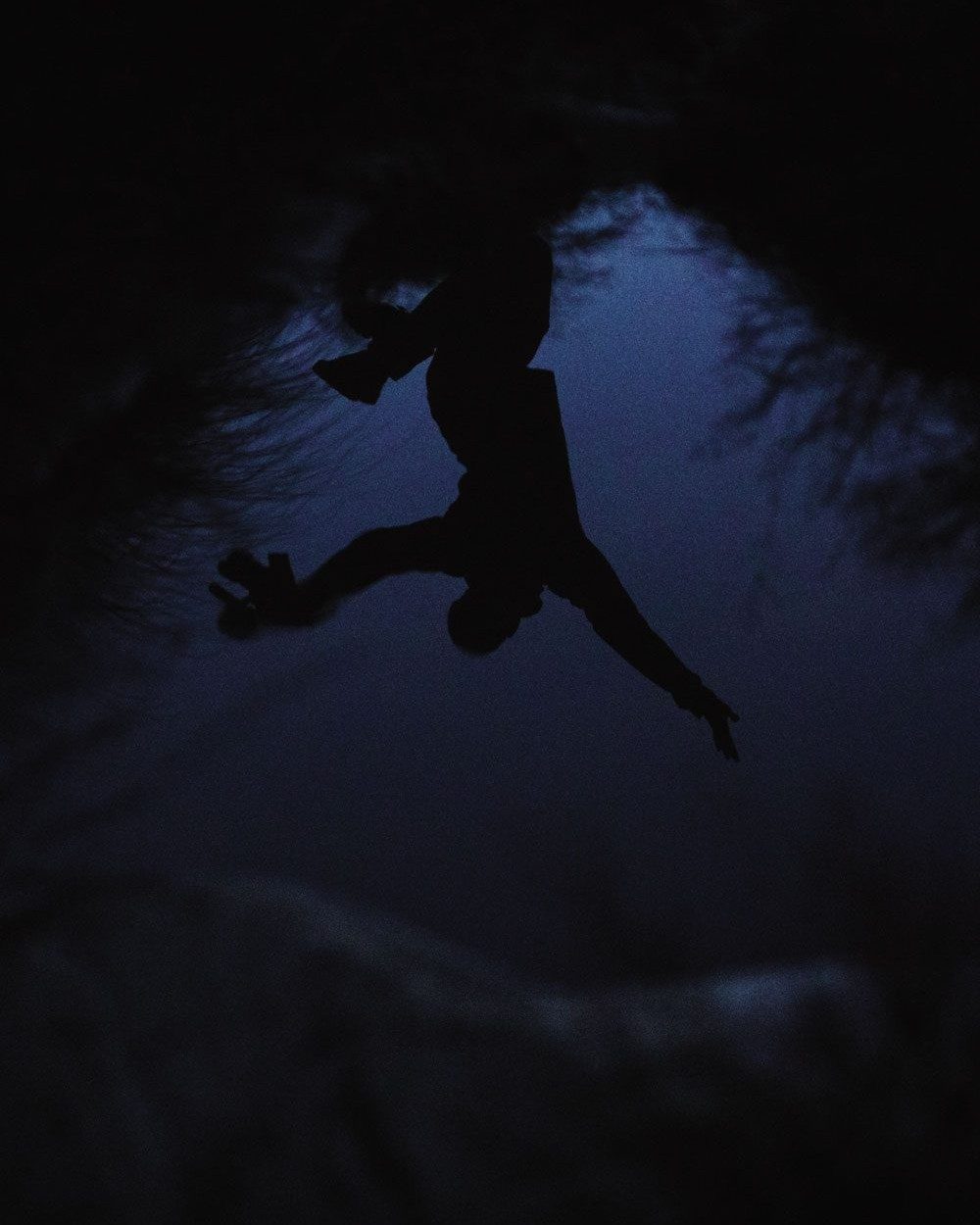

It ended with four women, one baby, a dog and a dead alpaca. Not exactly what we’d pictured as Claire and I piled ourselves, nervously laughing, onto a plane in New Zealand. Our plan was pretty simple: ride the best singletracks in South America; make friends; drink beer. A good plan. What we found was an ever-strong group of women, three days of backcountry free riding under the shadow of Mount Ausangate, in the Peruvian Andes, and a wee reminder that from little ideas, big things can grow. Mt Ausangate lured us in from day one. Wherever we went, there she was, our backdrop to Cusco, beguiling us into looking beyond our simple plan of just riding some trails. Whispers of the amazing scree fields, wild views and wonderfully lonely ridges were described. We had been messaging Nicole and her buddy Emily. Nicole runs Haku Expeditions, a bike tour company out of Cusco, specialising in taking people down fatigue-inducing, arm pumping singletracks for a living. Cusco singletracks are distinguished by their twenty- five kilometre stretches of uninterrupted downhill, occasionally broken by ancient Inca staircases or a few alpacas to dodge. This is where Nicole guides every day. The Ausangate fire was lit. Like a weird biking version of Tinder, we made plans to meet up for a ‘test ride’ to see if we all got along. In Peru, women who are of the mountains are called la cholitas. It was evident after our first ride together that our little idea had grown into us venturing up there and following the local cholitas who had walked before us. Nicole described our trip as a hike-a-bike without air. At a maximum of 4800m, pedalling in any direction was going to be hard. And this trip would have a lot of climbing. We had Emily, America’s collegial cross country, ST and omnium champion, to rally at the front; Claire, the ever- enthusiastic Scotswoman, to keep us in high spirits; and Nicole’s baby, Joachim, with his own nanny Iris who, as a local to the area was a mountain woman in her own right. We were also bringing Simon, a trail dog and, as we later discovered, an overly enthusiastic alpaca herder. Add a few pack horses and our mish mash of a team was formed.

AFTER PHOTOS WERE TAKEN, HUGS WERE GIVEN AND MOMENTS OF AWE WERE EXPERIENCED, WE FOCUSED ON RIDING THE RIDGELINE. RIDING THE RIDGE WAS A GREAT IDEA. BUT THE MOUNTAIN HAD PILED ITSELF WITH BOULDERS.

The Big Traverse.

It was a 3am start from Cusco to our starting point, where we’d rendezvous with the horsemen and helpers we’d hired to help lug bikes. Late morning saw us starting along a rocky walking path, bouncing around rocks and alongside creeks, before the only path we would see for two days ended and the inevitable uphill loomed. Soon the rocks were too thick to ride through. We were already at 4200m when we started the climb. Our helpers, long-time friends of the mountain, grabbed our bikes and took off ahead. We took turns pushing Emily’s bike up, taking five minute turns. But, as we went up in altitude, it turned into counting out ten steps before the next person took over. Soon I was having trouble catching my breath and was reassigned the responsibility of carrying the camp soccer ball. Altitude requires patience. Patience to go slow and patience to breathe. Each pedal up tested that. Pulling up on the ridgeline on day one to see the valley unfold below us will be one of those completely happy moments I will cherish forever, mixed with undertones of queasy high-altitude breathlessness. We were so pleased to be living in that moment in time, despite the spattering of sleet. Our trail off the ridge was absent. It was straight down, pick-a-line freeriding through a boulder park. It plunged us into high alpine scree fields, needle sharp grass, steep descents and icy blue creeks, dotted with the occasional farmer’s hut. Day two began easily enough, riding a meandering alpaca path through a valley. Our route was set to a fairly easy pass up ahead. This was until Claire hatched the great idea that the ridge framing us to the left would make for great riding. So we climbed, first to the false horizon, and be one of those completely happy moments I will cherish forever, mixed with undertones of queasy high-altitude breathlessness. We were so pleased to be living in that moment in time, despite the spattering of sleet. Our trail off the ridge was absent. It was straight down, pick-a-line freeriding through a boulder park. It plunged us into high alpine scree fields, needle sharp grass, steep descents and icy blue creeks, dotted with the occasional farmer’s hut. Day two began easily enough, riding a meandering alpaca path through a valley. Our route was set to a fairly easy pass up ahead. This was until Claire hatched the great idea that the ridge framing us to the left would make for great riding. So we climbed, first to the false horizon, and finally reaching the highest point of 4800m. Claire was in her element. Emily bounced around taking product shots for various sponsors. I, however, lay behind a boulder trying to find my breath. From behind my boulder I remembered this had all evolved from a little idea about riding some bikes, yet here I was standing (or, at that point, lying) higher than I’d ever been, on an unbelievable mountain mission, with an amazing bunch of women. After photos were taken, hugs were given and moments of awe were experienced, we focused on riding the ridgeline. Riding the ridge was a great idea. But the mountain had piled itself with boulders. So, instead, we carried bikes along the ridge towards the pass. It was hard riding for the next few hours. With no trail to follow and boulders thick on the ground, a lapse in concentration ended in pedals colliding with rocks or a dead stop. Hours of rock hopping lead us down to the lip of a giant bowl, with rough tracks peeling off left and right to the lake and camp below. It was steep, technical, off camber and exposed. I was mildly terrified as I dropped over the lip. At the bottom of each steep section was a ridiculous switchback framed with cactus on one side and a cliff on the other. Ill-timed braking sent my back tyre sliding towards a drop off and I tensed knowing things were going to hurt. By some miracle I pushed out of it only to crash, amid cheers, on the next switchback. When we reached the end of the rock garden, we were welcomed with wide, steep, grassy fields to gleefully freeride down to camp, with Simon leading the way. This is where Simon, our trail dog, took centre stage. He was our fearless leader. Our mascot. Our guardian from all things hairy. But Simon had taken to chasing alpacas. Despite continuous scolding, Simon could not help himself and chased a group of less-than-timid alpacas. All twenty of them chased him back. Simon became somewhat less fearless and hid behind Nicole and her bike as the group of rather angry alpaca surrounded them both. The standoff lasted twenty minutes or so, with Simon whimpering behind Nicole. The rest of us watched from the ridge above, consoling Nicole on the radio but assuring her that nope, we were not coming down to help. Twenty minutes later, the alpacas, in synchrony, turned and walked away. We were almost at camp, incident free. But Simon again charged off into a group of alpacas that were grazing just away from camp. He chased one young alpaca into the rocks and the alpaca broke its leg. After a little discussion between the head herder and Nicole, an exchange of money and a large apology, the alpaca ended up on our dinner plates. A pachamanca, a tepee shaped BBQ furnace, was prepared by Rocky and a few of our horsemen. The whole camp was fed and, I’m sorry to say, alpaca is delicious. There is something so joyful about the simple act of riding a bike. Day three was that day. It was one of those sunshiney days that make you happy to put your smelly bike socks on for the third day in a row. Or maybe we were just giddy from breathing oxygenated air again. The ride out was framed by the lake we had camped along the night before and led us to a river crossing. Claire and I opted for the shoes off, cold but drama free, wading approach. Nicole and Emily, however, decided to use the bridge up ahead. A three-rickety-pipes-tied- together-to-make-a-bridge-above-a-rather-large-and- rocky-drop later and everyone was across and on the final stretch for the homecoming downhill flow. The trail guided us through farms that rested on the side of the valley and wound its way back to our pickup point.

THAT LITTLE IDEA TO RIDE BIKES IN SOUTH AMERICA SEEMED SO FAR FROM WHERE WE’D ENDED UP. MAYBE IT WAS THE UNENDING ENTHUSIASM AND DESIRE TO PUSH OURSELVES THAT DROVE US UP THE MOUNTAIN. OR MAYBE IT WAS A SIMPLE FALLING INTO PLACE WITH THE RIGHT PEOPLE.

Journey’s End.

In Inca lore, Mt Ausangate is an Apu, the mother mountain spirit; the source of all good things and a caretaker to her land. She looked after us. That night, we reminisced back in Cusco over beers and burgers. That little idea to ride bikes in South America seemed so far from where we’d ended up. Maybe it was the unending enthusiasm and desire to push ourselves that drove us up the mountain. Or maybe it was a simple falling into place with the right people. The mountain let us make our little ideas evolve into something more; that we could grow a team that pushed each other when we needed, supported when necessary and cheered each personal accomplishment with wild abandon. It allowed us to connect with women who identified as moms, pro bikers and wilful wanderers. Our mish mash group of girls had taken a little idea and grown it into our own mountain adventure. As simply as we had come together, we were about to disband. I talked about a wee rest on a nice low-altitude beach somewhere. That was until Nicole let it drop that Haku Expeditions had organised a riding trip with Brett Tippie the next week…. But, that’s another story.

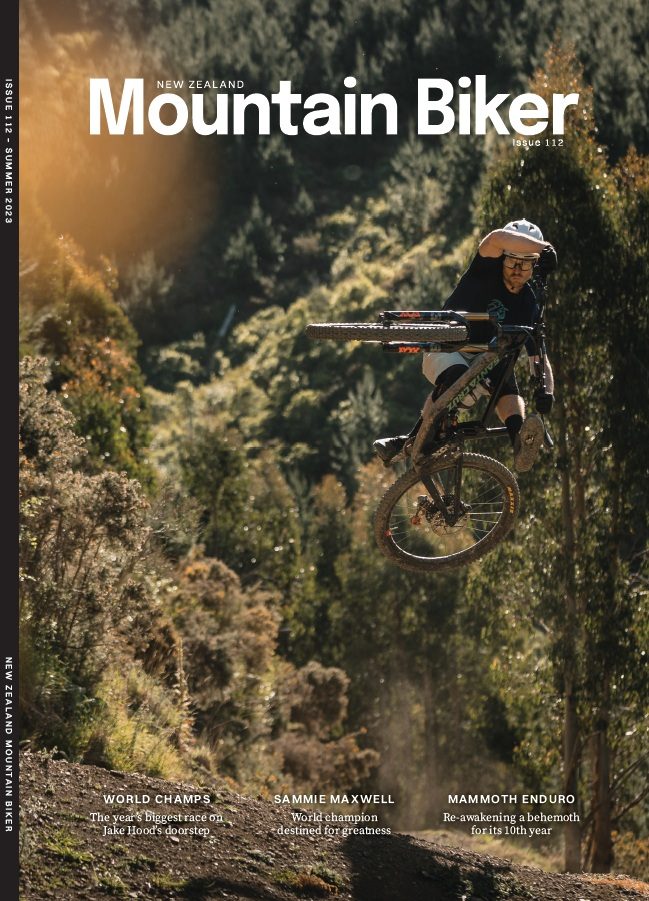

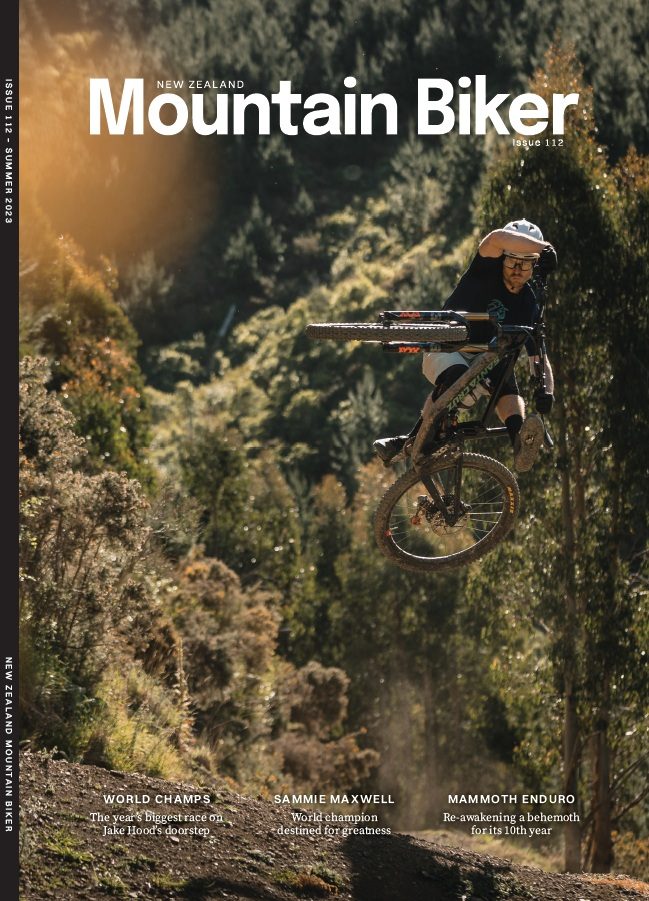

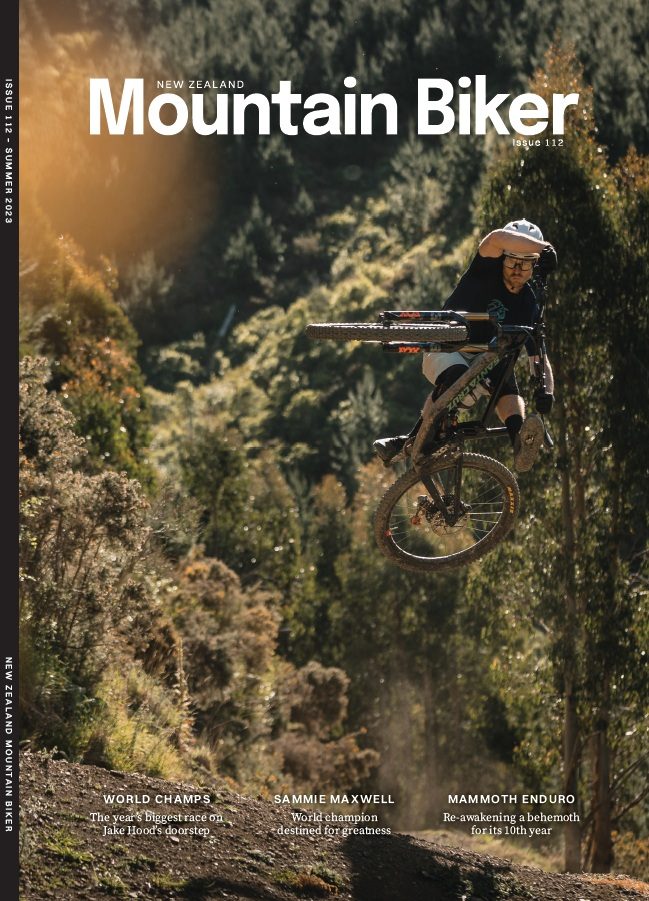

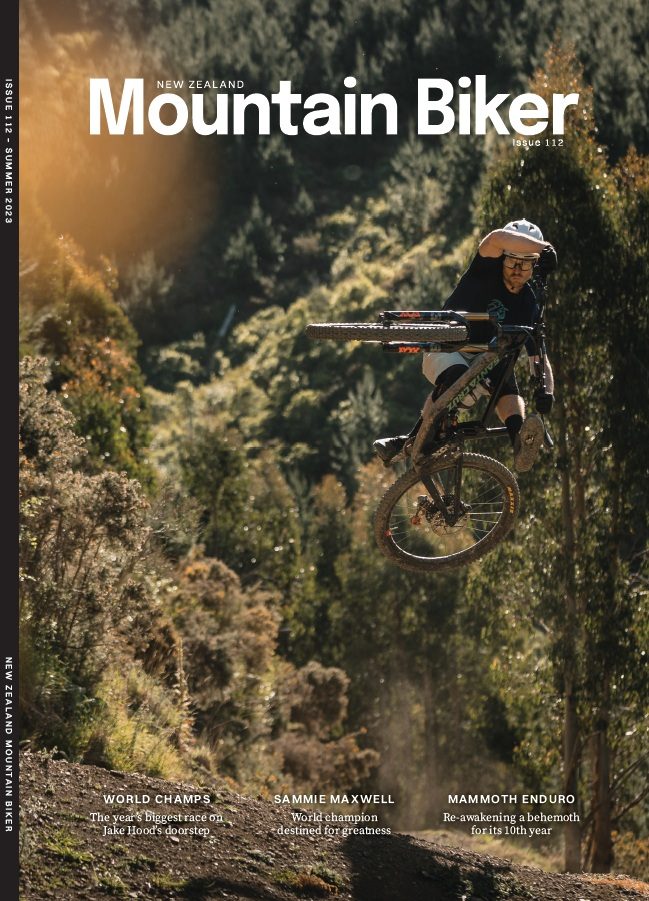

Sammie Maxwell - Destined for greatness U23 UCI World Champion

Words Lester Perry

Images Cameron Mackenzie

Some would say XC is dead (they’re wrong) and others would say we’re seeing a worldwide XC Racing Resurgence. Word on the street is that livestream viewing figures for XC far surpass those of the downhill, and those tuning in are treated to action-packed racing across all categories at each round of the XC World Cup.

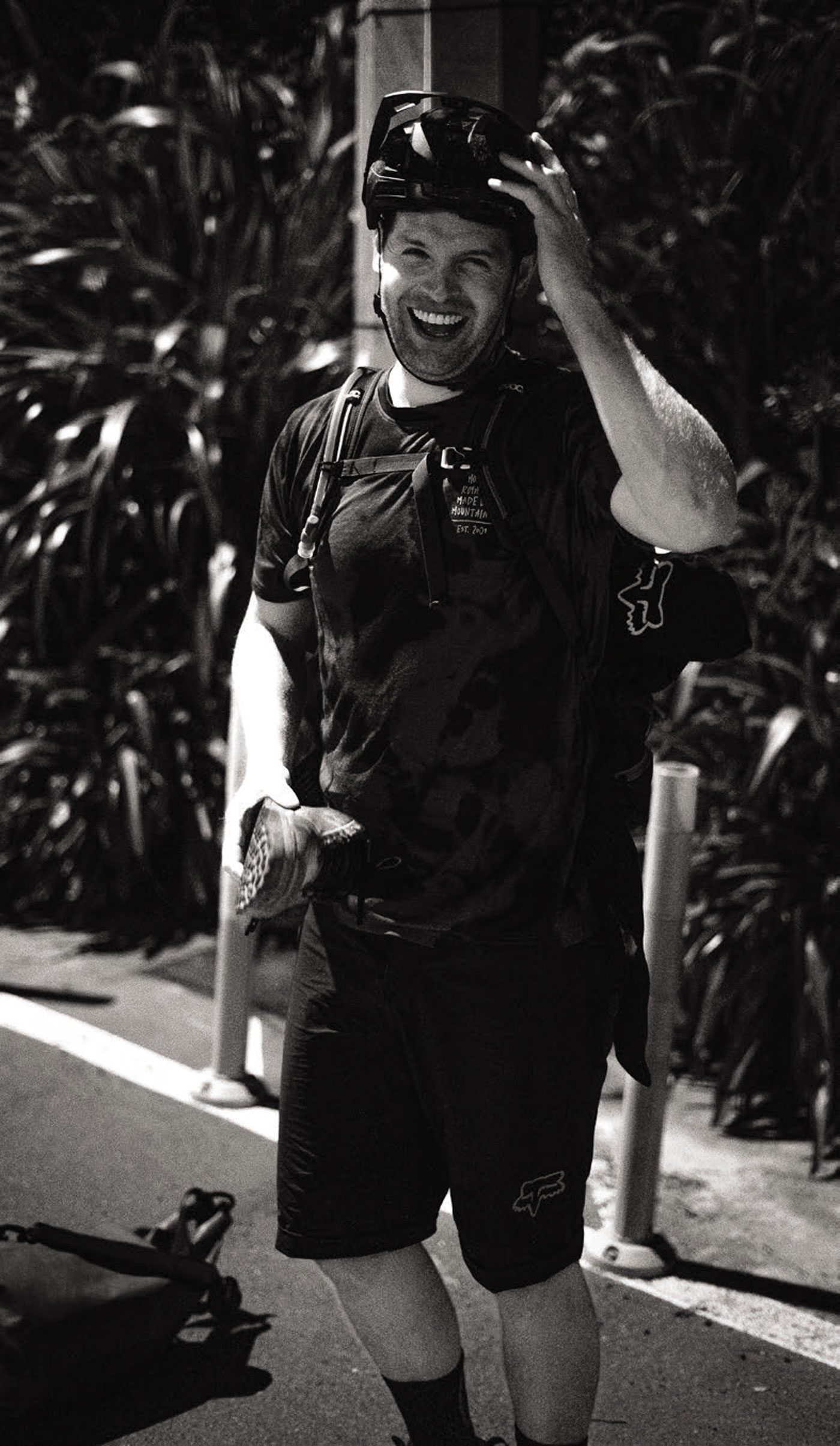

It’s been a long time since we’ve seen a Kiwi XC racer hit the World Cup scene with the impact of Sammie Maxwell. She first appeared on most casual fans’ radars at the beginning of the 2023 season, and they’ve seen her climb the ranks, race after race, to become the World Under 23 champion for 2023, and finish the World Cup Series in 3rd.

Anyone who has been immersed in the sport for the last few years, particularly here at home in NZ will know Sammie didn’t just burst onto the scene in 2023 but has been on this path for a few years. What has brought her to where she is now -a World Champion and a strong contender for an overall World Cup title? We were fortunate enough to dig a bit deeper into what makes this fun-loving, small-town girl with a huge grin tick!

Although not from a particularly sporty family, living in Taupo – just minutes from the lake – an active lifestyle is more or less a prerequisite. Although studious and high-achieving at school, early life was so much more than study and learning. The freedom and flexibility Sammie’s environment offered meant that netball, trampolining, running, Pilates, triathlon, football, swimming, cycling, rock climbing, horse riding and more, were regulars on her to-do list, although she was equally happy to lie in a hammock and read a book. Anything that required energy or had an aspect of competition and Sammie was sure to be front and centre!

“I stayed in Taupo throughout all my schooling and certainly consider myself a ‘small town’ girl. I would enjoy the odd trip to the Mount with my grandparents where we would go to malls, etc but after a few days, the traffic and the shops would all lose their ‘exciting’ factor, and I’d much rather have the quiet Taupo streets!”

It’s commonplace for high-performing female athletes to excel in most areas of their lives, and Sammie is no different, slotting right into this stereotype. Throughout the early years, her inquisitive mind and passion for learning were continually stimulated by her parents; both high performers in their fields -her father an engineer, and her mother a laboratory phlebotomist. For years, Christmas gifts included books about biology and physics. A consistent top performer in her academic group throughout college, Sammie was awarded DUX in her final year. “In year nine, when our biology teacher gave us an assignment on a disease, we could pick whichever we wanted, and just research about it. I chose chickenpox because I had recently had Shingles (both caused by the varicella-zoster virus -Ed.). Being my typical curious self, instead of just reading a few lines of Wikipedia and calling it a day, when I got home from school that afternoon, I went straight to our massive bookshelf and got the five biggest medical textbooks mum had used while doing her study. I read everything I could about the virus, the immune system, the physiology of the disease and treatments. I became obsessed with the amazing ability of the immune system and knew from that moment on that I wanted to work with biomedical science.

“It’s fair to say that my teacher also agreed when the feedback for my report read something like: “Sammie, I asked for a college assignment, not something that looks like an abstract out of a university thesis”.

Sammie’s competitive nature spurred her toward mountain biking. “My brother and dad would go riding and I guess I wanted to be like them and join their adventures. I loved being ‘tough’ with the boys. When I was young, I would always be throwing myself into things my brother was doing – to try to impress him I guess. My dad would always buy us a McDonald’s ice cream after riding, and who was going to turn down a bribe like that!”

Alongside MTB rides with her family, Sammie picked up triathlon, meaning time spent road cycling. But she knew MTB was really where her heart was, even in those early years. “I love both types of riding and the road and MTB community in Taupo is so amazing, I really am lucky to have been involved in both; however, I always knew that when it came to racing, MTB was what I was best at and what I wanted to do.”

Sammie’s enthusiasm for all things biomedical science, and keenness for mathematics, led her to study a Bachelor of Biomedical Science, moving to Wellington to study at Victoria University. She graduated in 2022 with a Bachelor of Biomedical Science Majoring in Molecular Pathology.

While training her intellect at university, Sammie was finetuning her racing craft on the bike, building the engine that has since lead to her success. Balancing a demanding study schedule with a strict training regime is a tough challenge and many an athlete has cracked under the pressure. Sammy powered through and, after graduating, began working in a research lab specialising in mRNA therapies and neurological disease research. She has a bit of a Clark Kent vs Superman vibe; outside of work life revolves around her training, but a quick change of costume, donning a lab coat, and she’s all business. “I have had my fair share of 5am wake-ups for training, and working until 8pm to fit everything in,” explains Sammie.

“I am lucky to have a great group of supportive people around me who can identify when I’m running low on energy (sometimes running on cortisol alone!) and remind me to take a break -often meaning dialling back the training a bit until the energy catches up. It’s hard work and definitely not something I could do all year around, but in the few months before heading for Europe, it’s nice to do one last push of mahi to remind myself how tough the ‘real world’ can be before jetting off to frolic around Europe for summer with my bike. It makes me very grateful when I am in Europe, and has taught me some intense work ethic which I pride myself on. In Europe when I have a big training day, I always remind myself I still have it easy – I could be in NZ doing that ride in the cold rain, in the pitch black at 6am – giving me an energy boost and making getting out the door a bit easier.”

All the hard work is now reaping rewards, but it’s been a long journey. Sam Thompson has been working with Sammie for five years, since pre-Covid times – first through the CyclingNZ Performance Hub but, after its demise, through the NZ MTB Academy. “We saw riders like Sammie prosper and develop exceptionally well under the MTB Performance Hub programme. When that was shut down there was a real gap in the development support network that needed to be filled. The NZ MTB Academy makes it possible to provide these athletes with professional support (coaching, sport science, strength and conditioning), professional guidance and also some financial support, to help bridge the gap from amateur to professional, and then also support them when they reach that professional space as well.”

In 2019, Sammie attended her first World Champs, in the Junior category, gaining useful experience and finishing in 14th. With racing on pause through the Covid period, Sammie used her time to address some issues which were hampering her success. “I have struggled with under-fuelling for a long time and spent a lot of time during Covid working with an Eating Disorder specialist, and psychologists, to get on top of this. So this year (‘23), when I showed up to Europe, I had a lot more maturity and was ready to start racing and recovering like a pro, to get through the season without fading.”

It wasn’t until 2022 that we saw Sammie start to settle into her groove on the world stage; the hard work of the previous years starting to pay off. It’s obvious from her results at the two world cups she raced in 2022 that her build to the top began back then, and was only exacerbated heading towards the 2023 season thanks to her methodical training and self-belief.

Coach Sam commented; “What stands out from others is her ability and belief to never give up, and her consistency of training. I would have trouble finding a session in the last five years that Sammie simply hasn’t done because she’s put it off. She simply doesn’t miss a session.”

Trusting the process appears to be one of the keys to Sammie’s progress. The 2023 season has shown a consistent build right from back in May at the World Cup opener in Nove Mesto where she finished 8th.

“It was always the plan to not hit the season at peak form – especially since this is my first full season, and we didn’t know how my body would react. So we decided to start a bit slower and use the first few WC races as ‘form builders’ to introduce the intensity needed for racing. It was part of the plan to let the form physically improve through the season – but I think the biggest change was just gaining confidence in my ability and working my way through the starting grid.”

Following Nove Mesto, a month later, the World Cup circus headed to Lenzerheide, Switzerland. A confidence-building 6th place for Sammie and a solid build towards Leogang where we’d see a major breakout performance, with a 2nd place in the XCO after a tough Short Track (XCC) race to open the weekend. Two weeks later things were beginning to click in the XCC and Sammie crossed the line in 4th, the perfect primer for the XCO three days later. Another strong ride and into second at the XCO at Val Di Sole. Confidence, experience and physical form were all coming to a head just in time to peak for her season goal: the World Championships in Glentress, Scotland Then, on the 12th of August, Samara Maxwell became U23 Women XCO World Champion! After a dominant ride, distancing the field on the first climb, she eventually crossed the line draped in a New Zealand flag, having made history; the first Kiwi woman to win a Cross-Country world championship.

“In the days leading up to Worlds we had made a minor suspension change, but everything else was pretty much the same. I think just steady training for a few weeks with some good days over the local ‘cols’ and riding with Ben Oliver helped a lot; I accumulated stress on the bike but Sam (coach) and I were also watching closely because we knew the worst thing we could do would be to accumulate too much fatigue and dig myself into a hole before the event which can easily happen during pinnacle points in the season.

“I was lucky also to have the help of Louis Hamilton in Scotland; he showed me the best lines to take on the course and, as a privateer, this is something I don’t have access to at World Cups, so I owe a lot of my success on the day to him!” Sammie now had the spotlight firmly on her as she steamrolled into the remainder of the season. Heads were turned and everyone wanted some time with the “fresh face” in the pits, who they’d seen grow and develop quickly through the early season. Her secret was out and she thrived on meeting and chatting with so many new people who were discovering this fun- loving, Kiwi world champion for the first time.

“The people are amazing, and the sport is growing so much -it’s awesome! Changes to broadcasting this year allow people back home to watch my races and that’s helped increase the number of people following the sport and created a very exciting atmosphere at events. The girls I race with are amazing and I’ve met some amazing friends this year -I am just so excited to watch this sport develop over the next few years!”

Prime conditions and a strong race in the XCC rewarded her with second place at the opener in Pal Arinsal, Andorra. Sammie’s first outing in the XCO World Champs stripes would come a couple of days later, and in the toughest conditions of the season so far. The venue was hit with storms in the hours leading up to racing, forcing schedule changes (meaning no live feed) and leaving the course sodden and slippery. The form was there but conditions -and the venue being at over 2000m elevation –meant Sammie couldn’t unleash what was required to be back on top, finishing a credible 4th place.

Les Gets was next on the calendar and another dominant display in the XCO where she effectively put her competition to the sword on each climb, putting the group under pressure every time the gradient tipped up. After multiple lead changes throughout the race, Sammie finally made it stick on lap three, taking the lead once and for all, and maintaining a 30-second lead. It wasn’t all said and done, however, and she narrowly avoided catastrophe; crashing on a grassy off-cambered corner in the closing minutes of the race. Fortunately, her gap to second place was enough, and she limited her losses to cross the line with a stellar dance move finish line celebration and take her first World Cup win!

Never one to completely relax, Sammie has taken up learning French this season to keep her mind busy between racing and training. In years to come she’ll be getting plenty of French language practice, after a mid-September signing to high profile, French-based team, Rockrider Ford for the remaining 2023 races, and through until 2026.

“It’s been a dream ever since I can remember to be a professional cyclist. I’m beyond honoured to say, that thanks to Rockrider Ford Racing Team, this dream is finally a reality. I already feel so at home in this team and have had the biggest, warmest welcome. It only makes me more excited to see what we can achieve in the future together.”

With all of the downsides of being a privateer now being taken care of, Sammie can focus solely on being a professional athlete, no longer stressing about having no income while racing across the world. With the mental load of finances and logistics now removed, preparations for next season are already underway. One of Sammie’s goals is to improve her technical descending, an area where she and her coach identified she’s been losing time to her competitors.

Sammie came out swinging at the debut race for her new team in Snowshoe, West Virginia for the XCC World Cup Round 7. Another solid race battling Ronja Blöchlinger for the win but narrowly missing out, finishing second. Snowshoe’s XCO race shaped up to be another epic battle with Blöchlinger, but this time it was Sammie who came out on top. It almost wasn’t to be though, and she narrowly avoided a huge crash on the opening lap, washing the front wheel out on greasy rocks and colliding with a tree, fortunately she stayed upright. Sammie put in a cracking ride, regaining her composure to go blow for blow with Blöchlinger in the early laps. Sammie continually pulled time on the climbs, and by the mid-point of the race had taken lead for the final time, growing the gap for the remaining laps to take the win by a minute, marking a perfect start with her new team.

Next up was a trip across the border to Mont-Sainte-Anne, Quebec, for the eighth and final race of the 2023 season. Blöchlinger rounded off her perfect XCC season with her eighth win, just pipping Sammie for the win again, and collecting valuable overall series points. The XCO race saw the toughest conditions of the season; rain had set in, making the technical course even more technical for even the most skilled riders, leaving them battling not only each other, but the conditions and course as well. At times, the race looked more like a duathlon than an XCO with most riders taking to running sections at times. Thanks in part to Stephan Tempier’s line coaching, Sammie rode the technical sections confidently.

“I was able to ride everything in the wet, even really tough sections that the elite were crashing on, so that was a huge positive. It meant I felt safe and confident and was able to have sooo much fun slipping and sliding my way past people!” Proving her mental resilience after a start loop flat tyre; she chipped away at the field for the entirety of the race, eventually finishing fifth, securing herself third place in the overall series and cementing herself as one of the world’s top XC riders. When asked about any wisdom she wished she had known earlier in her career, and what tips she’d pass on to other young women looking to break into the World Cup circuit, Sammy offered some clear advice:

“Never feel like you’ve got to make sacrifices or suffer unhealthily to succeed. In our heads, we often think elite athletes are insane people who have super-human abilities to suffer, and when it comes to physical training yes, they do suffer, but when it comes to their mentality, the top-of-the-top athletes protect their mental health above all else, and this is something that’s taken me a while to figure out. If our brain is unhappy or starved of the joy and energy it needs, we will never be able to perform at our true potential. So always make sure you are looking after your body and giving yourself the rest you deserve! Plus, eat the damn dessert! I spent too long turning down yummy foods because I thought it was what a real athlete would do – when in reality, ice cream is your superpower! “What it takes to win should be sustainable and enjoyable. You need to believe in yourself, and you can’t do that if you keep feeling like you are having to change the way you function or change what you want to do to succeed. It should come naturally. I can say I wasn’t acting any different for my lead into Scotland than I was during the middle of winter last year in NZ – once again it’s just a matter of trusting the process, loving what you do and enjoying yourself while you put in the work!”

No one gets to the top alone, and it takes a village to support an athlete as they work their way there. Sammie wanted to pass on a special thanks to all who’ve helped and supported her in this journey so far.

We’re excited to watch her develop and see where Sammie’s career takes her as she steps into Elite for the 2024 season. One thing’s for certain: that grin of hers will be showing up in race coverage for many years to come!

Royale with Cheese Part 2

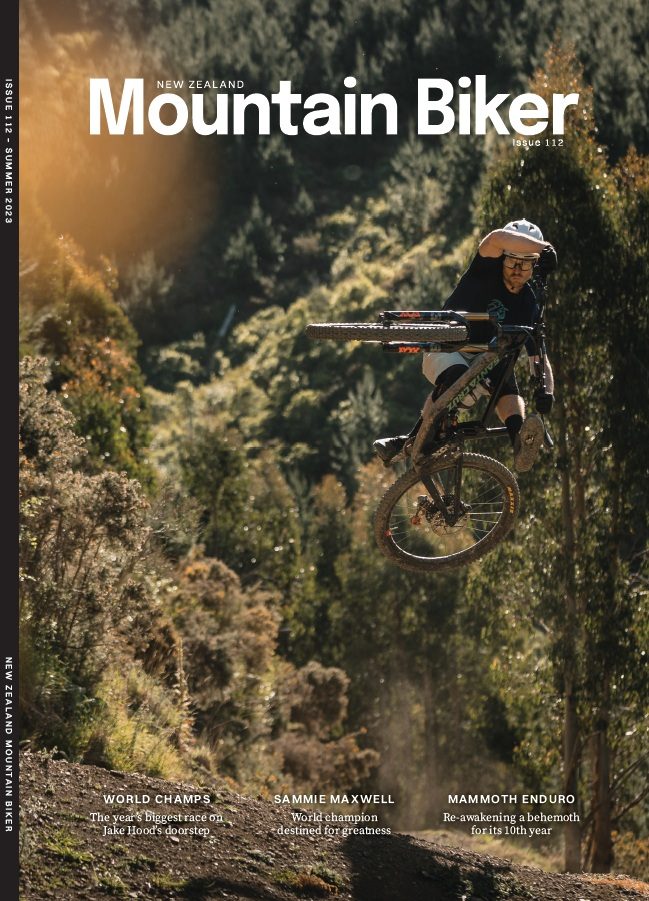

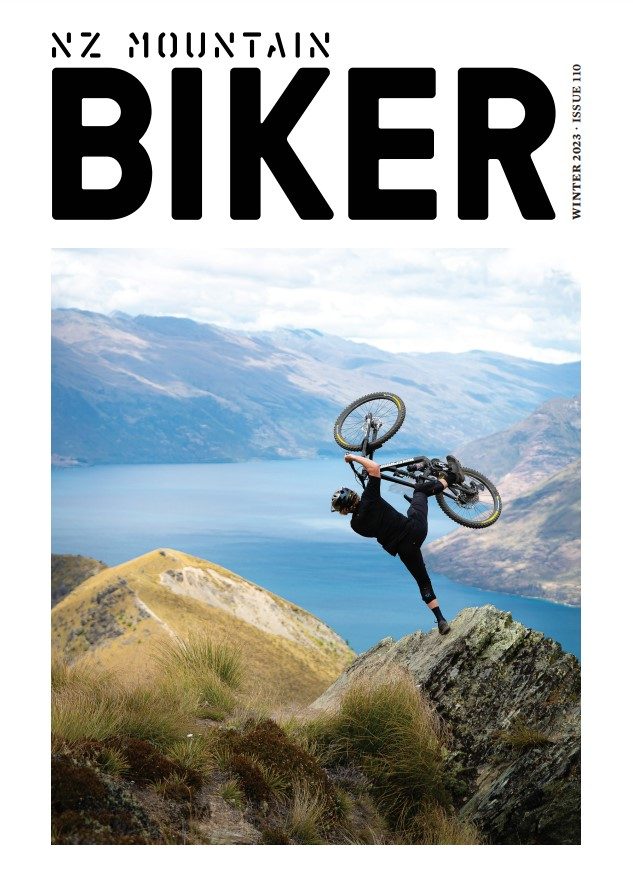

Words & Images Jake Hood

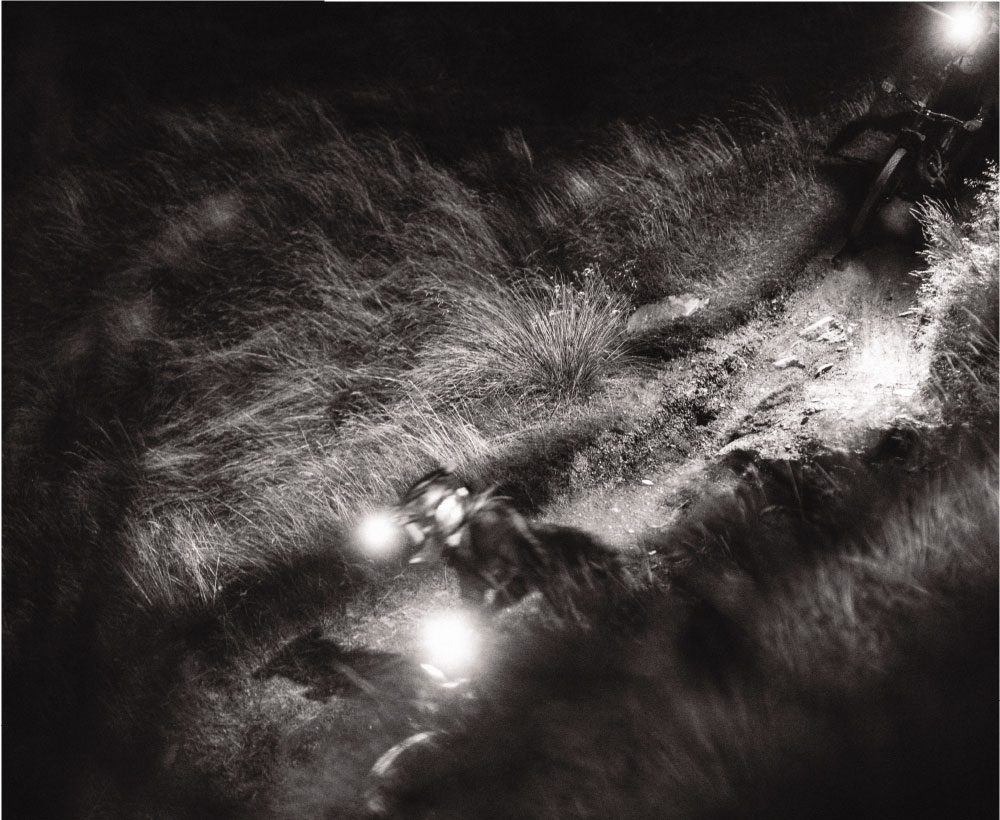

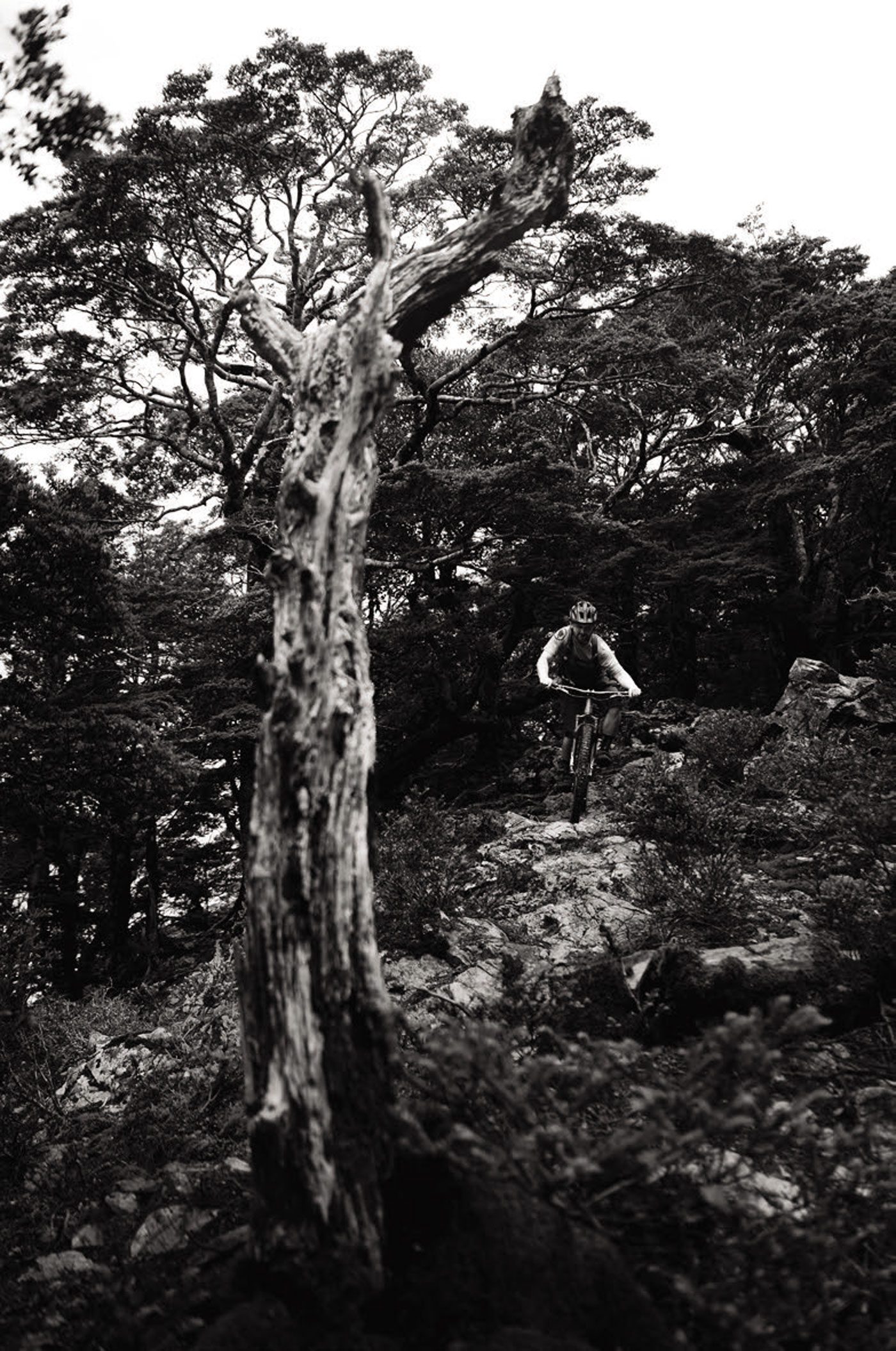

Our day started early. We packed up all our stuff, and left behind the items We didn’t need to take up royal. then we set off. the morning started With a tiny bit of technical sWitchback trail, then an off-the-bike hike down a cliff to the riverbed below. the dirt Was a lot drier than the day before, Which Was a good thing because it seemed like the day was going to be technical.

We hit the riverbed, crossed a small stream, and reached the start of the Mt Royal walking track. To begin with, it was a bike-on-your-back approach -we were literally climbing up a cliff face with our bikes. The rock we walked on was covered with moss, and we had to think about where we were walking and where our next step would land us. Once we got past that point, it was just a pretty steep, relentless push for about an hour before it mellowed out. It was one of those hills that is steeper towards the bottom and mellows the further you go up. The soil changed as well. It was pretty clay-like at the bottom, very slippery in the wet. The further up we got, the less present the clay was in the soil, giving it a more predictable nature. The foliage and cornflakes (some might say ‘loam’) that covered the trail seemed to get thicker as we gained more altitude. You could tell this trail wasn’t used that often; it wasn’t a worn-in, obvious track like many of the others in the area. There were a few times we lost the track on the way up. The trees were spaced pretty far apart, leaving heaps of space to hold it wide open on the way down. The trail wiggled its way up the mountain, covered in a spiderweb of root gardens. Some of them had huge roots that created large steps to get over, potentially causing a wheel stopper or going over the bars. I later found out this was the case.

Near the top, we stopped for a spot of lunch. I think we’d have been pushing up for about three hours or so by that point. It was pretty hard going. We stopped at a beautiful little opening in the trees that gave us a great view of the Richmond range. Mt Fishtail lay just before us. What a mountain that was. Lunch chat consisted of more talking shit about Bradshaw almost bailing and how good the DB Draught was going to be at the pub that evening. You could see the top of Royal from the spot. We had to descend along a ridge for a little bit before the final push up into the rocky alpine. It was going to be about an hour to the top.

It wasn’t long, though, before the chat ended up beIng about cold frothy beers and food at the pub later on. how good were those beers going to be?

No one wanted to descend the ridge first; it was pretty damn steep -and none of us knew how slippery it was going to be. The track sort of just disappeared, and it was a bit of a pick-your-way-down, trying to find places where you could get some good braking in. Turns out that going first was probably the best option, though. The locked rear wheel scraped off all the good foliage to brake on, and left behind slick black sludge. If you locked the front brake on this, you would know about it – but it was fun to pick our way down.

As we pushed up the last stretch, the trees started to thin out and the trail was more defined from here through the rock and scrub -nature hadn’t taken back the track like lower down. It was a bike-on-the-back hike up through the loose big rocks and some nice big bits of slab which made up the trail. My legs were starting to feel numb and heavy on the very last bit of the push; that pre-bonk feeling. Thank God the top was close. As we rounded the final bit of the mountain to the summit, the wind started to howl. It was strong, and our bikes acted like sails in it. The last stretch was a small walk along the flat to the top. Woohoo! We had made it to the summit of Mt Royal.

It was a clear day, and you could see for miles. There was a blue haze over all the hills. To the west, Mt Fishtail basked in the sun above the rest of the Richmond Range. To the east, you could see Blenheim, the Cook Strait, and the very faint outline of the Wellington coastline. The 360-degree views were stunning and the endorphins were kicking in – that high you get from reaching a summit. High-fives and hugs were thrown about, with smiles all around. These are the moments we do this for. Well, that and the fact we had a flipping awesome descent back down to the hut ahead of us. The howling wind was pretty chilly, so we chucked on some layers and found shelter just off the top, behind some rocks, to enjoy the view for a bit before we headed back down. You have to savor these things.

The trail eventually led to the point where we had to get off and hike back up to the lunch spot. From there, it was all downhill back to the river. What a time to be alive.

It wasn’t long, though, before the chat ended up being about cold frothy beers and food at the pub later on. How good were those beers going to be? This thought quickly prompted us to get back on our bikes and start heading down. Off the top, you have to ride along the flat, leaning your bike into the side wind until you start tipping into the trail. Paul, Scotty, and Cappleman were keen beans and started attacking the rocky shale alpine. Big long rock slabs covered in wheel-sized cracks, with drops off them into foot-sized loose rocks that moved below your wheels, made up the track. There were a couple of switch-back turns which made it even more fun. The sound of the terrain moving below your wheels while your bike danced through the chunder was delightful. Bradshaw was making light work of it on his hardtail, with a massive smile on his face. As the vegetation started to appear, the surface became more gravel-like, and the trail became more defined. Scotty, Paul, and Cappleman were off on a mission. The trail flowed along the ridgeline, turning left and right through the scrub. It had small undulations that you could use to pump or pop off. The surface was soft and gravel-like with some rocks and cornflakes mixed in. My bike felt amazing -the suspension was just fluttering along through this stuff, tires were hooking up a treat as I weighted the bike into the turns. You could feel the side knobs carving into the loose ground.

As the Beech forest thickened, the trail started to steepen. We stopped at this steep roll feature that we had looked at on the way up. It looked like a goer, and the way around looked pretty ugly. It was just a matter of if we would be able to stop after. How much speed would you pick up off of it? Would you be able to slow down before the turn into the next shoot? Paul tipped in first and greased it, making it look easier than it should have been. From there, we all hit it. It was a fun feature. In the dry, you could have hussed off it.

The trail eventually led to the point where we had to get off and hike back up to the lunch spot. From there, it was all downhill back to the river. What a time to be alive. The trail followed the ridge along for quite a while; not super steep, just enough of a gradient to keep the speed up without pedaling. The faint trail flows through Beech forest and is covered in deep, mossy foliage. The occasional fallen tree covered the track, but some logs had been placed in front of them, turning them into a feature to huck off. We whistled our way along the ridge, freeride flicks happening everywhere, foliage and sticks flying from the tires into the air. The bikes danced over the slippery roots and rocks that lay beneath. The trail would go from flat out to a few slower speed turns and back to flat out. There were whoops and hollers coming from everyone.

One ridge led to another, and things started to steepen up. Just off the ridge was where the trail took us. It was steep, covered in deep leaves. The trees were sparse, and turns in the trail were long and sweeping. This was my favorite bit of the trail. The dirt was super slick under the leaves, and you could drift around the turns with your foot off; opposite locking on the way in and letting the back wheel slide out on the way out. Just left, right, left, right. It was amazing. So much fun. I just could not wipe the smile off my face.

A second wind must have hit us because we started hitting it hard. the pace increase was insane. The pub wAsn’t far awAy; it was in sight, like a glowing beacon of happiness.

After that bit of speedway fun, the trail popped back out on the ridgeline. You then work your way through a long section of janky rocks, which meant travelling at a slower speed than what we had ridden so far. Thinking about lines was key: be precise. Momentum did help, but going at it full attack wasn’t going to end well. Personally, I love this stuff. It’s a challenge to ride. It takes skills, balance, and confidence to get you through.

After that bit of tech, you come off the ridge and back onto the face of the hill. It was a bit of a choose-your-own adventure at times since the track just disappeared at points. We were just pointing our bikes down the hill and following our noses till we found the trail again. Fallen sticks cracked and snapped under our wheels – it was a lot of fun. The further down the trail we got, the more technical it got, and the speed started to reduce. The huge wheel-trapping roots started to come out. You had to be on your game; think about your line, commit, and hold momentum through these. One of these wheel-trapping root sections caught me and sent me out the front door. Luckily, I was okay and landed in the soft foliage.

The steepest part was the last – and potentially the sketchiest – bit of trail. It got really steep, with huge steps into compressions. The dirt was clay, so grip was at an all-time minimum. We rode some of this, but the compressions were hard on the body, and you really had to find a flat platform to come to a stop to control your speed. The green, mossy clay dirt was doing its best to help the tire slip and slide. The bottom was so close, and you could see the riverbed…. and also the cliff you would ride off if it all went wrong. Sensibly, at this point, we decided to get off and hike down the last part. It just wasn’t worth the risk. I even managed to slip just pushing down, which resulted in my falling on my bike and bending the derailleur hanger. Shit. It wasn’t good. It looked fairly bent, but I would have to assess it back at the hut.

We scrambled down the last bit of cliff/trail to the riverbed. Fuck yeah. Royal was done. What a trail that was. Different from everything else I have ridden so far in the Richmond Range. It just had so much variety. It was wide and fast with some tech features mixed in, and less scary to ride than Fishtail or Riley. God, it’s amazing what you can do on modern mountain bikes these days. Bradshaw was the man of the match on his hardtail. What a guy.

We stopped for a quick look at the vieWpoint overlooking picton before We rode down the road into town, grabbing the bag of clean clothes We had stashed two days earlier out of the bushes. We had done it.

The day wasn’t over, though. We had to get back up to the hut, pack up and load up the bikes, then get out to the Canvastown pub. There were still a few hours of hard work ahead. We crossed back over the small river and scrambled our way back up the basically-a-cliff-face to camp.

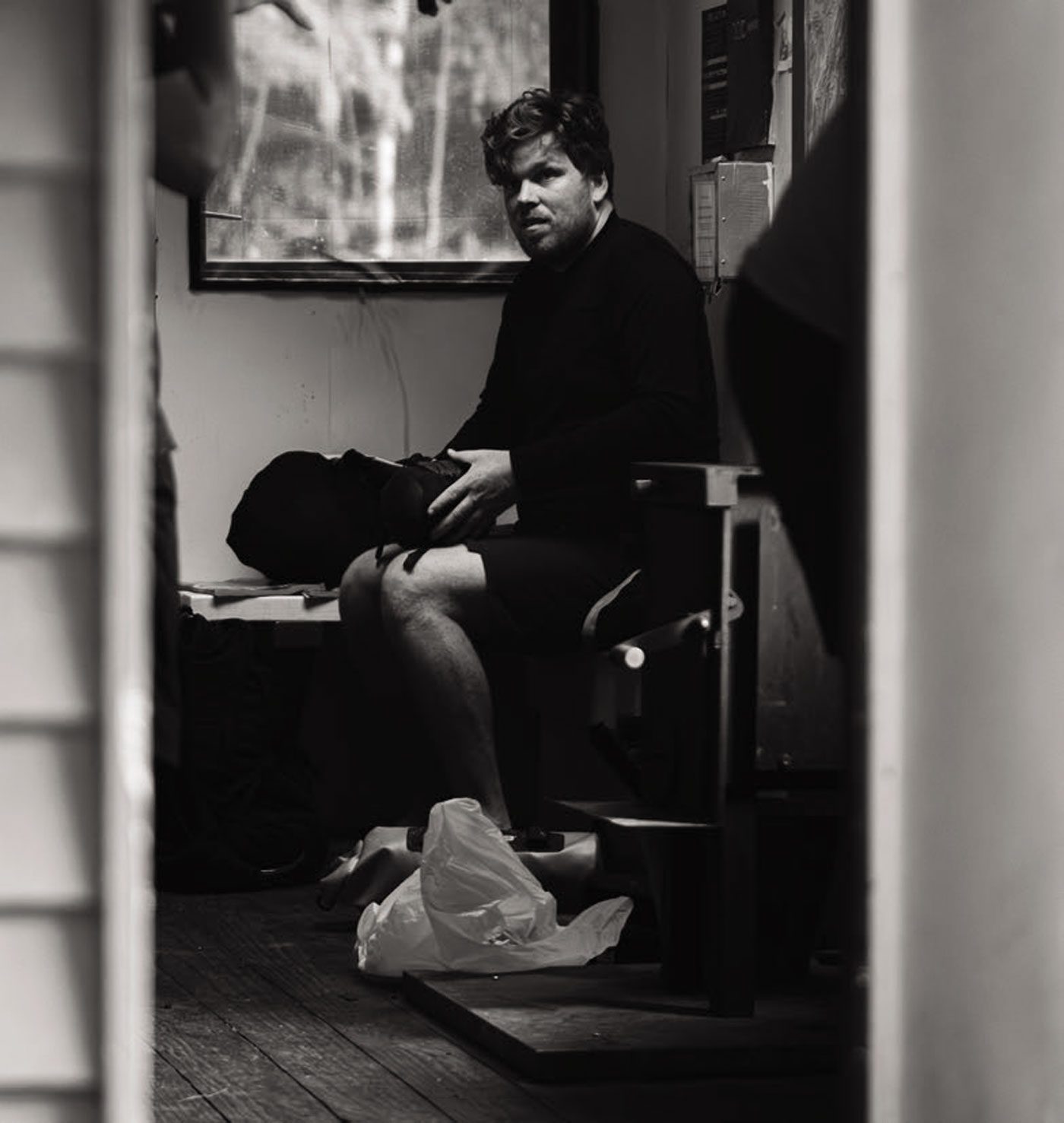

“I’m glad you bullied me into coming up. That was fricking epic,” Bradshaw jokingly said. It really was. Back at the hut, we loaded up the bikes. Well, Scotty, Paul, Cappleman, and I did. Bradshaw instead decided that he was going to completely unpack everything and repack it all again, which might not sound funny but, when he’s doing it in his underwear (for some reason), flailing around like a wobbler in the long grass, which was very bee and wasp-populated, it made for some very entertaining watching. Especially every time he got stung. We were in stitches. “What are you doing?!” we yelled at him. After about 15 minutes, we got bored and headed off onto the trail out, as we didn’t want to get stung. It must have been another 15 or 20 minutes before Bradshaw joined us. Wobbler of the Week, right there.

Seven kilometres of trail lay ahead of us, back to Butcher Flat campground, then a 15km ride to the pub at Canvastown. By this point, we were all pretty tired and over it. The inevitable come down from the high was happening, and the next part was going to be a bit of a chore. It’s funny how many emotions you go through on these big days. As we headed back out on the trail, I could feel that my legs were pretty weak. The hiking up had taken it out of them. I had to walk the steep pinches in the trail as the bent hanger had taken away the ability to use the top gear. Amazingly, the rest of the gears were fine. I was going to have enough to get me back to Picton. The SRAM AXS is pretty damn great. I just got my head down and pushed through. It wasn’t a super fun trail to ride out, more of a means of getting somewhere but, after about an hour, we arrived at the road back to Canvastown. The pumps got wiped out. Tires inflated to near maximum PSI for extra rolling speed. Time to grind this road out.

Something must have come over Paul and Cappleman because they decided to set off at a blistering pace, leaving the rest of us behind. I had my headphones in, listening to a podcast, and sort of just hit the road at my own pace, spinning up the climbs and pushing a bigger gear on the flats. Scott and Bradshaw were a little ways behind on the road. I think their legs were dead. I just got my head down, zoned into the podcast, and spun away. I made sure to enjoy the place I was in. This valley reminded me of my home back in Scotland; very green, lots of farmland, and pine tree forests. Having ridden the road the day before, there were certain landmarks I recognised, giving me an idea of how far to go. Boy, I was excited for a beer at the pub after this big day. As I passed Bradshaw’s grandparent’s hut, I knew it wasn’t far – just 2km or so. By this point, Scotty and Bradshaw had caught me up, and we got in a chain gang. A second wind must have hit us because we started hitting it hard. The pace increase was insane. The pub wasn’t far away; it was in sight, like a glowing beacon of happiness.

The bikes got parked up. Paul and Cappleman had found a good seat and were already on the beers. DB Draught was the only real choice. Now, I’m a bit of a beer snob, but there is something great about a cold DB Draught after a big day. I think it’s just made even better by the fact you’re drinking it in this old, rural pub. The pub had recently been taken over by new owners, and the place was pumping with regulars. It had a very homely feeling. Somewhere you could just settle in for a big shift, and that’s exactly what Paul was doing. The man was putting them away like they were water. By the time I’d finished one, he would have done two. It was a bloody great drop though; refreshing, crisp, just perfect. We settled in and reminisced about the day. It had been so great -awesome crew, amazing trail, and just the perfect amount of struggling. How good.

After a few more pints and an amazing dinner at the pub, the beer buzz of bad decisions kicked in, resulting in us getting a box to drink back at the hut that night. As it was starting to get dark, we hit the road back to the digs in good spirits. Back there, the box opened, and we continued into the night, with Bradshaw providing the entertainment again by unpacking and repacking everything as we watched him struggle. “What are you doing?!” we yelled, again.

The next morning, we were woken early to the sound of Bradshaw leaving. He was off early to ride to Nelson before a storm rolled in. The rest of us slept in a bit longer due to slight headaches from the beers. Today was going to be the easiest of the lot – we just had to get back to Picton before 6pm for the ferry back to Wellington. It was another overcast day with breaks of sun; not too hot, not too cold. Great weather to work our way back around Queen Charlotte Drive. My legs were feeling good this day for some reason; strong, powerful. I wished they had been like that over the last two days. It would have made life a lot easier. We stopped off in Havelock for breakfast and picked up some stuff for lunch. The pace was kept steady. We had all day to get to Picton. No big rush. It let us just enjoy the day and the ride. Really soak up the beauty of the place. We stopped at Ngakuta Bay for a swim in the sea, and lunch. The sun was out. The sea was the perfect temperature. Just tremendous.

The final 11km were stunning. One last climb before descending into Picton. I had Hybrid Minds playing in my earphones as we knocked off the last bit. The perfect soundtrack to the last bit of this adventure, speed tucking our way down the wavy road to Picton. The lush green canopy of trees and the views of the bays, mixed with the euphoria of completing this mission, made for a magical moment. What a time.

We stopped for a quick look at the viewpoint overlooking Picton before we rode down the road into town, grabbing the bag of clean clothes we had stashed two days earlier out of the bushes. We had done it. The Royale with Cheese ticked off. Another mission done, and it was yet another great one.

We had a couple of hours to kill before the ferry, so we got some second lunch, went for a swim in the sea again, then downed a few pints in one of the waterfront bars. We chatted about the mission we had just done; it wasn’t as hard as Ferry to Fishy, but it was a further distance. Breaking it into three days definitely made it a more pleasant experience. The ride around Queen Charlotte Drive was far nicer than the main highway to Fishtail. This time it seemed like the perfect amount of Type 2 fun (although you could argue that the more Type 2, the bigger the reward at the end). Royal was an absolute treat to ride, and getting to tick off some of the Wakamarina was a huge bonus. You couldn’t have asked for a better crew as well; just the best. We left the Capital on a Saturday morning, rode kilometres into the backcountry, rode a big mountain, rode back – and we were going to be back in the Capital by Monday evening. How good! Weekend adventures done right.

We boarded the ferry back to Wellington, found some good seats, and settled in. We hadn’t even made it out of the Sounds before we started talking about what was next. What’s going to be the next one we tick off? We have a few ideas in mind…. Watch this space.

Welcome to Scotland

Words & Images Jake Hood

“There’s no such thing as bad weather, just inappropriate clothing,” This is a common saying that’s thrown around in Scotland. Well, whoever said that is a flipping idiot, I thought to myself as the rain hammered down on us at the start of the men’s DH final in Fort William.

The rain drenched everything in sight, showing no mercy; not even my triple Gore-Tex 50,000 waterproof Montbell jacket stood a chance. Welcome to Scotland.

This year would see the inaugural edition of the UCI Cycling World Championship. Yes, there have been World Champs before, but this is slightly different. Instead of just select events being held in different places worldwide, it would all be condensed into one country over 11 days. There were 115 events and 101 para- events over 13 different disciplines. There would also be a medals table for the countries competing, like the Olympics and (also like the Olympics) it’s to be held every four years. The inaugural one was to be hosted by Scotland.

With a big break in the Enduro World Series between rounds, it seemed like no better time to head back to the motherland to watch some events. It had been four years since I was last there – four years too long. I’d almost forgotten that it rains a lot in Scotland, though I was quickly reminded during my eight week stay. I managed to only get three days without it raining, to some degree, throughout the day.

The downhill was going to be held at the world-famous Fort William track. It has been a staple on the circuit for years. My first experience of being at this place was the World Cup in 2005 as a young lad. It was a magical place. I was in awe of the pits, the riders, the bikes, and the track. The place was packed with people and, walking around the pits, I would stare at the bikes for hours, fascinated by them as well as the riders fly down the track at stupid speeds. It was incredible as a young lad. That year, Steve Peat won and I’ve never heard a sound like it when he flew across the Visit Scotland jump into the finish area. The crowd erupted in noise that built in a crescendo until he crossed the line and won. At that point, it was like an explosion of sound and emotions. It was defining. People cheering, banging things, blowing horns. I get goosebumps even just thinking about that moment. When people talk about being at Fort William WC, they often talk about that energy.

Fort William last held the Downhill and XC World Champs back in 2007. I was at that race as well and it was a wet, wild week. Sam Hill dominated the men’s field to take the win, and Sabrina Jonnier won the women’s, but it was Ruaridh Cunningham (the Scotsman) who stole the show by winning the junior males DH and giving Great Britain its first rainbow in downhill.

I forgot just how beautiful the drive up to Fort William is if you head via Glencoe. The rolling green hills and farmland of central Scotland gradually turn into dense woodland, sparse heather-covered mountain areas, and sparkling lochs. It’s a beautiful drive that is very popular with tourists. As you enter Glencoe, you are greeted by towering, almost vertical, mountainsides that enclose the road. The valley floor is lush and green, crisscrossed by streams and rivers. Waterfall’s cascade down the mountainsides, and the atmosphere is one of wild, untamed grandeur. It’s a landscape that exudes both awe and a sense of isolation, but it’s also a reminder that it’s rugged up here. You have to respect the landscape, or it will bite back. Admire it, but treat it well. A short time after you finish driving through the glen, you arrive in Fort William. Above the town towers Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in the UK. It’s sparse and covered in rock. From a distance, it doesn’t look like there are any signs of life on there and it serves as a reminder that you’re in the Highlands now.

KIWI JNR. WOMEN

SACHA EARNEST, ERICE VAN LEUVEN, POPPY LANE

The respect you have to treat the outdoors with transfers to the downhill track on Aonach Mor. It sits three mountains over from Ben Nevis. It’s a historic track; rugged, hard and fast. A course of three parts, it’s 2.9km of bike-smashing, arm- pump-causing, leg-burning hell of a track that descends 547m. The top half weaves its way through the open moorland and its surface is made up of gravel, granite slabs, and rock. Rock graders litter the way down the track. It’s unbelievably rough. Spectating trackside, you often hear the sounds of rims being smashed into the super hard granite. You do not want to crash up here. During race day, spectators will walk down the track through the moor, trying to avoid the bogs and slipping in the peaty soil beneath their feet. I, for one, didn’t manage this and took a few tumbles. After the open section, you make it to the most technical part of the track, the woods. By this point, your arms and legs are burning. You’re struggling just to hold on, but you have to navigate your way through the twisty, wet, muddy, root-infested bit of track before holding as much speed as you can onto the motorway. You might not win the race in the wood, but you can certainly lose it. One mistake could cost you a lot of time. Finally, you make it to the motorway. A long run into a hip jump catapults you into the row of jumps that guide you to the finish area. It may seem like the simplest bit of track, but it’s proven to be a very crucial part of the race. Races have been won and lost here before. To finish off the track, you jump into the finish area before descending down the “wall” into the last jumps and drops of the track before you cross the finish line. It’s a savage track, unique to everything else that gets raced, one that always provides thrilling finals.

Though it is remote, people from all over the UK flock to this race. It’s incredible just how many of them make the trip. On race day, there’s a sea of people throughout the pits and up the hill on the track. Sometimes it’s hard to stroll through the pits because of the number of people. The UK fans really get into it; some dress up in crazy outfits, and some dress down. Occasionally, you get the odd streaker. The true spirit of the event, though, is the wild camp. Located not far from the event, a 20-minute walk maybe, a large farm field gets turned into a campground for the weekend, with a mix of tents, vans, and campervans. It has real festival vibes, and huge parties happen there that go on until the wee hours. People wake up hungover only to continue drinking to help get them ready to watch the racing of the day before continuing to get back on it for the rave that evening. It’s a non-stop party all weekend.

THE RAIN continued to lash down, SATURATING EVERYTHING IN SIGHT.

There are a couple of essentials you really need to pack if you decide to come and watch this race. First of all, bring your waterproofs. At the end of the day, we are in Scotland, a country synonymous with bad weather. It might be forecasted for sunny skies throughout the week, but this is the Highlands. The weather can turn on a dime. So be prepared and pack those waterproofs. The other essential, and I mean essential, is getting yourself some Smidge. What is Smidge, you might ask? Well, in Scotland, we have these little pests called midges, which are basically tiny flies that love to bite you. They truly are pests. They will swarm around you, biting you all over. No part of you is safe. If you’ve been to Scotland, chances are you will know how bad they can be. They suck, but Smidge is a spray-on repellent that keeps these little insects at bay. I’ve warned you. Don’t get caught out because you will know about it.

The weather was on and off throughout the week and played a pretty big factor in the race. It stayed good for the day of the juniors and qualifying races; what a day that was for NZ. Poppy Lane was one of the first to drop in the junior women’s category. She put down a blistering run that saw her comfortably in the lead and onto the hot seat. Junior woman after junior woman tried to beat that time but couldn’t. Poppy was in the hot seat for a long time, looking surprised every time a rider came down and didn’t better her time. Sasha Earnest laid down a great run and got close to Poppy’s time but ended up 0.417 seconds behind. Was anyone going to be able to deny the win for Poppy? There were two riders left at the top of the hill: the fastest qualifier, Erice Van Leuven, and fan favourite, Aimi Kenyon, from Scotland. Erice had been dominating this year in DH and Enduro and, at Fort William, it was no different. She blitzed the course and came down into the lead by 5.208 seconds. It was a huge lead. Both Poppy and Sasha ran over and hugged her with a NZ flag. Were we going to witness history being made? Aimi Kenyon came down. The crowd was roaring and cheering her on, but she was back at the top in the first two splits. Poppy and Sasha were hugging Erice tightly in the hot seat. They were all tearing up. As Aimi hit the jump into the finish area, Erice knew she had done it. Aimi crossed the line in fourth place. It was a New Zealand 1, 2, 3. The girls got up and celebrated. I think they were shocked at what had just happened. I was tearing up watching them hug each other in joy; it was an emotional moment. The crowd was going wild. What an incredible thing to witness. It’s fair to say that the future is bright for New Zealand in women’s downhill racing.

In the junior men’s race, Germany got their first DH world champion. Henri Kiefer took the win with Canadian, Bodhi Kuhn, taking second place, and Léo Abella of France rounding out the podium.

The following day was the main event: the DH finals. As I rode to the event with my brother, his partner and my niece, the weather was looking pretty great. A few clouds around but mostly sunny skies. It looked like it was set to be an epic day of racing. There were thousands of people flooding into the event. Fans were everywhere: in the pits, up the track, in the grandstand. The food court was packed with people drinking and eating. The slight breeze and warm weather kept the dreaded midges at bay. The pits and expo village were bustling with people trying to see and get up close to their favorite riders while they got prepared in the pits. There was an energy about the place. It was going to be a special day.

U23 UCI WORLD CHAMPION

SAMARA MAXWELL rode a truly dominating race

I managed to get there in time to catch a little bit of practice before the women’s event started. Emmy Lan was the first to drop, setting a time of 5m26.653s. From there, the times tumbled and tumbled. It seemed like every rider that came down was just going faster and faster. After the first 20 riders, Tahnee Seagrave was sitting on the hot seat. A pretty incredible feat after her huge crash into the barriers a couple of days before. Phoebe Gale came down to knock Tahnee off, only to then be knocked off by the local – and crowd favorite – Louise Ferguson. The cheer was huge when she crossed the line. People were stomping their feet in the grandstand, cowbells were shaking, and old bike parts were getting smashed together noisily. The MC was getting the crowd hyped up. The noise was biblical. It was a British 1-2-3 with 10 riders to go. A couple more riders came down, but it was still a British 1-2-3 until France’s Marine Cabirou came down and smashed the current leading time by 7.36s. That put a stop to the possibility of a British winner. Camille Balanche came down 0.341s faster. She was in the lead with two riders to go. Only Nina Hoffmann and Vali Höll could deny her a second rainbow jersey. Nina was up at the first split but behind at the second, but a crash in the berm just after the road gap would dash her chances of taking the win. Vali Höll was last to drop. She had been on form this year. She had seemed to have found her groove this year in elites after making some big mistakes in her first year. She was dominating the WC series for 2023 and did the same in Fort William, laying down a championship run. Making short work of the track and winning by 2.020 seconds. She was the only female to set a time under five minutes. Back-to-back World Champ wins for Vali; and I’m sure it won’t be the last for her. At the end of the women’s final, the weather was still holding out. It was hot; the sun was shining, and it looked like it was going to stay okay for the men’s race. As the first 30 men came down, it was holding, but the dark rain clouds were starting to show their ugly faces around the tops of the mountains. As the Scotsman, Greg Willison, was on his run, the heavens opened. Light at first before getting really heavy – I’m talking big- ass droplets of rain that soak everything. Greg came down to take the lead by 7.753 seconds. A few riders later, Angel Suarez came down just to pip Greg by 0.47s. It looked like Angel was going to be the last guy with a dryish track. I thought to myself: “This might be it; there’s no way someone is going to beat that time on a wet track. Is Angel going to win? Is it going to be one of those races that’s decided by the weather?”

The rain continued to lash down, saturating everything in sight. I got my waterproof jacket and pants on but it was so wet that, after five minutes, I was soaked through. From the grandstand, all you could see in the crowd was a sea of umbrellas. The track had completely changed. Riders were still putting down fast sections in the top, due to the fact it actually gets grippier in the wet but, from the woods down, it was a different story. Rider after rider came down, absolutely soaking wet and still pushing by the bottom, but no one was even remotely close. It looked like they were at war with the track, rather than racing it. I really thought the race was done… until Matt Walker came down. He was up at splits one and two and had made light work of the woods. It looked like he was going to be up coming into the motorway, until he had a huge crash. His front wheel slid off a metal bridge, and he drove himself into the ground. It was horrible to watch but, somehow, he got up and was okay. Maybe the dry times were beatable in the wet, but it would have to be a helluva run. Danny Hart came down and was looking good, but he lost around two seconds in the final split. Charlie Hatton was up next. I was hanging out with Innes Graham at the time, chatting with him about whether he thought Charlie might win the race. Innes had been working as a line coach for the GB team all week. “I reckon Charlie could be a good shout; he’s been looking so fast all week. Very consistent with his riding. It could be him,” he explained. Charlie set off out of the start gate. He was up at the first split. He was up at the second. He was riding amazingly. So smooth, fast, and controlled. There were no wobbles or bobbles. The third split was green as well. It was a master class in how to ride in the wet. He hit the motorway, and the split was green again. The crowd was going crazy. He was going to better the dry time. He jumped into the first arena and crossed the finish line. We had a new race leader! Charlie Hatton had mastered the wet conditions to take the hot seat by 2.464 seconds. The crowd went mental! There was so much noise. It was crazy! “I think that’s the winning run,” said Innes. Rider after rider came down, but no one could beat the time. Laurie Greenland came down and got closer than anyone so far, making it a British 1-2. The Austrian danger man, Andreas Kolb, set off out of the start hut. He was faster at the first split and faster at the second. He was up; on the run of his life. Was he going to topple Charlie? He came into the woods at a ridiculous speed but had a bit of a ‘moment’ and lost some time. At the third split, he was 1.5 seconds back. Not an unachievable amount to make up on the motorway, but it would be hard. At the fourth, he had made up a bit of time. He crossed the finish line; it was going to be close. There was a split second of silence, 0.599s back. Charlie had kept the lead. Andreas in second. There were three left at the top of the hill, any of them capable of winning. Troy was the first to drop of the three, but he was unable to better the time. Loic Bruni was next. His run was amazing, but it wasn’t enough and so it was fourth place for the Frenchman. Loris Vergier was the last man to leave the hut. He was behind on all the splits. As he hit the finish area, it was clear that he wouldn’t be able to better the time of Charlie. As Loris crossed the finish line, there was an almighty cheer. Charlie had done it. He’d ridden the run of his life – a true master class of a ride – like a true champion. He bettered everyone – in terrible conditions. It was a magical moment to witness. His family and friends jumped the barriers so they could hug him. What a way to finish off the DH weekend of World Champs! A British rider taking the top 1st and 3rd spots. A British-made bike in first and second. What a way to round out what might be the last ‘world’ level event at this epic race venue of Fort William (there are rumours going around that that was the last race at the venue).

THE NOISE WAS CRAZY

The following weekend, the XC World Champs were held in my hometown of Peebles. Well, specifically, Glentress Forest, about 3km from Peebles. I pretty much grew up in this forest. I rode there every weekend as a kid. I worked in the bike shop at the bottom of the hill for years. Many, many years of my life had been spent there, and now the World Champs were going to be raced here. Crazy. There had been some Enduro World Series events raced here in the past, but I never thought in my lifetime I would see World Champs being raced here. It made me proud to be from there and to have grown up in this small part of the world.

Peebles had really gotten behind the event as well. Bunting was hung up all along the high street. The local businesses had lots of bikes and World Championship-themed displays in their windows. The local butcher had made a special pie for the event. There was a buzz and energy around this normally sleepy, unassuming town. Throughout the week, you would see XC race bikes parked outside the cafes and coffee shops.

The event organisers had built a special one-off course just for this race. It was a really well- thought-out course that would make for some exciting racing. It used a mix of old walking tracks and fire roads for steep, pinchy climbs. Existing bike trails were used, mixed in with some freshly cut technical descents and climbs. There were a couple of gap jumps, with the man-made rock roll, The Salmon Ladder, a crowd favorite. It was quite technical and impressive to see being ridden with the seat up. The rest of the course used the new development of bike trails that had been built at the bottom of the hill. It mixed and linked different trails together. A great way to showcase this yet-to-be-open part of the hill. It was a course that had a bit of everything, keeping the riders on their toes and producing some exciting racing.

The first big event of the week was the short track. It’s basically a 20-ish minute all-out sprint on a shortened version of the XC course. I’d been to a few of these over the summer, at the World Cup events, and I have to say it makes for one of the most exciting events to watch.

The men were up first. Straight off the line, it was an all-out war as the riders battled each other to try take the lead and gain control going into the descent. Luca Schwarzbauer powered his way through and was in the lead into the descent. The fans were out in force, hanging over the barriers and cheering at the riders. There were a lot of lead changes over the laps. The crowd favorite, Tom Pidcock, had been working his way through the field after starting a few rows back. Sam Gaze had been hovering around the front, just waiting to make his move. Lap after lap went by. No one was really making any attacks. Watching them go by, I could not believe how fast they were going. The speed they rode the descent at was so impressive and, when they hit the start-finish straight, they got even faster; warp speed. I didn’t know you could go that fast on the flat. On the last lap, Gaze made his attack. He went on the climb, and no one could match his pace. He just kept pulling and pulling, almost like he had an extra gear. Tom Pidcock made a move as well, up to 4th before making a huge dive up the side of Luca Schwarzbauer on the last turn. Gaze held the lead across the line and took the win. Victor Koretzky in second. Tom Pidcock in third. It was a huge moment for Gaze and another Rainbow Jersey for NZ. Tears of joy, and a huge smile, were present on the normally emotionless face of Gaze as he hugged his partner. What a race that was.

Up next was the women’s short track. To say that Evie Richards was the people’s favorite would be an understatement. Throughout the practice laps, everyone was shouting “GO EVIE!” as she rode past. She was definitely getting the biggest cheers of the event, and it was understandable. The UK fans adored her. If you can say one thing about the UK fan, it’s that they are super patriotic.

The race had an explosive start. Just like the men’s, it was a race to be first into the descent to try to control the race. Italy’s Marina Berta led up the first climb. The big names were in close pursuit: Pauline Ferrand Prevot, Evie Richards, Puck Pieterse, Rebecca Henderson. There was a breakaway group of six riders, and that was where the race was really happening. Lap after lap, the lead rider of the group would change. By the halfway mark, it was anyone’s to play for, but one rider was playing it smarter than the rest. Prevot didn’t seem to want to take the lead, just sit in the pack, save energy, and wait for her moment. By lap seven, a few of the chasing pack had caught the leading group. Lap nine saw the first real attack of the race. Evie set off on her bid for the win. You could see in her eyes how much she wanted this. She went off. Prevot and Puck Pieterse chased. They broke away. Into the final lap, Evie was leading. The crowd was going mental. Was she going to do it? As they hit the climb, the patient Prevot made her move. She went, Puck tried, but she couldn’t match the pace – Prevot was in a league of her own. She went on to take the win. Puck would take second, and Richards would take third. Another super exciting race.

The following day would be another great day for New Zealand. Samara Maxwell rode a truly dominating race to take the win in the U23. She led from start to finish. No one was even close to her. She was truly in a league of her own in this race. It was an incredible performance to witness. Another gold for NZ.

Saturday was the big day: the Elite XCO; the final mountain bike event of the World Championships. Thousands and thousands of people descended upon Glentress to watch the show. The cycleway from Peebles to the event was so unbelievably busy with spectators riding to the event, and it was so cool to see. Fans lined the track with flags flying, vuvuzelas blowing, cowbells ringing. Places like the Salmon Ladder were completely packed, with maybe two or three hundred people in a tiny area, all watching their favourite riders tackle the technical section. The sun was out at the event but there were dark clouds lurking around, making for a moody atmosphere. It was shaping up to be one heck of an event.

2023 UCI MTB WORLD CHAMPS

Scotland, you did well.

The women were up first. Seven laps plus one start lap, making up 26km in total. How was it going to play out? Off the start, Puck Pieterse and Loana Lecomte made an early attack to get out front and take the lead into the first main climb of the lap. The short track champion, Pauline Ferrand Prevot, had a bit of a tough start, resulting in her trailing 16 seconds off the pace going into the first descent. The fan favourite, Eve Richards, was in the mix, a couple of seconds back. You could tell how much this race meant to her, just by watching her facial expressions. She was giving it her all but, alas, it wasn’t her day. Loana Lecomte put the hammer down on the descent to put a good gap between her and Puck. Prevot wasn’t going to let them get away, though; she set off in pursuit of Lecomte. After the first lap, Prevot had narrowed the gap from 16 to five seconds. She was on a mission. By the end of the first big climb on the second lap, she had passed Lecomte and was riding off in formidable fashion. She didn’t even look like she was trying; in a class of her own. It was her race. She went on to put on an absolute master class, taking her second set of rainbow stripes of the week. Lecomte would go on to take second, while Puck came in third. The final event was the men’s XCO. The riders lined up on the start line. Big names were getting announced by the MC. It wasn’t just big names from XC lining up, though. Peter Sagan was racing. Mathieu Van Der Poel was looking to do the triple after having won the rainbow stripes in road the week before, and cyclocross earlier in the year. Tom Pidcock and Sam Gaze were placed a few rows back. Eight laps plus one start lap – a total of 29km of racing lay ahead. It was an explosive start; straight off, people were sprinting to fight for position. Disaster struck for Van der Poel, though, as he washed the front on the turn into the start-finish line on the first lap. He was out. As the riders hit the first main climb, it was Jordan Sarrou out in front leading, with Nino Schurter close behind. Nino laid down the law on the descent and took the lead after the first lap, with Sarrou, Pierre de Froidmont and Alan Hatherly all within a second of him. Alan Hatherly made an attack and took the lead, putting himself in front, but where was Pidcock? He was making up places after his mid-pack start. He’d made it up to 11th and was on the move. Hatherly, Sarrou, and Schurter were starting to pull away from the main pack. At the end of the second lap, Pidcock had moved up to 5th, only four seconds off the leading pack. The crowd was going crazy watching what Pidcock was doing. It was a superhuman performance. Schurter and Hatherly put down the hammer, trying to put some time between them and Pidcock. Sarrou was dropped -he couldn’t handle the pace. Pidcock moved up to third, but it wasn’t long until he caught Schurter and Hatherly. The noise as he joined the leading crew was crazy; a massive cheer could be heard throughout the forest. Pidcock was pushing them, but only Nino could match the pace as Hatherly started to fall back. It was a two-way battle for the win, with three laps to go. Something was happening behind. The quiet Kiwi, Sam Gaze, had turned on the afterburners and was working his way through the pack like a man possessed – passing riders like they were standing still. It was crazy, the amount of time he was making up. With just two laps to go, he was up to fourth. Pidcock had taken the lead and was riding his own race. He was just in a different league on this day; no-one was even close. He would go on to win the race in dominating fashion. But the really exciting person to watch in the last two laps was Gaze. He passed Hatherly to put him in third, and was catching Nino. Could he do it? Come from mid-pack and get the silver? Near the end of the seventh lap, he passed Schurter. As they entered the final lap, Schurter tried to hold back Gaze but, alas, it was too late. Gaze powered off, leaving Schurter hurting. Gaze was riding so fast that he managed to claw back 12 seconds off the lead that Pidcock had in that final lap. He had put in a heroic effort to take the silver. Schurter would go on to take bronze. A huge crowd had gathered at the finish line to see Pidcock cross the line and take the rainbow stripes. Boards were getting banged, cowbells were ringing, and cheers were shouted. What a way to finish. He rode an incredible race, coming from mid- pack to take first by a big margin. Amazing! After the medals and jerseys had been presented, Tom travelled through the crowd, up onto the grandstand. He stood there with the rainbow stripes, gold medal, and a British flag around his back. It was a magical moment to witness. The crowd was going crazy. A true champion.

In the end, Britain took the top spot on the medal table at the Inaugural World Championships, with 56 medals. New Zealand took eighth spot, just behind Switzerland. Not bad for a country of 5.1 million people. Best of all, NZ beat Australia by a long way.

World Champs have always delivered a whirlwind of emotions, crazy stories and great racing – and this year was no different. Scotland put on a heck of a show. The crowds were crazy. The racing was fantastic. These had been races to remember and I’m glad I was back to witness them in person. Scotland, you did well.

Legend of the Mammoth est. 2013

Words Lester Perry

Images Cameron Mackenzie

In recent years, Nelson has boasted the highest number of sunshine hours in a calendar year. It duked it out for the title with the Taranaki region in 2022, but lost out to not only them but to the Bay of Plenty, too. If second place is the first loser, what’s third place?

Sure, it’s still a podium finish but not necessarily something to write headlines about. Nelson’s ‘sunshine-hours’ crown is gone for now, but residents can rest easy that they have plenty of other accolades to sing about. It’s not just the big yellow orb in the sky bringing visitors to the area and, while the overall vibe and culture could be compared to that of Taranaki, there’s one major feather in Nelson’s cap that the ‘Naki can’t come close to: mountain bike trails. We’re not talking about the “mountain biking” your uncle and aunty do on the weekends aboard their folding e-bikes (although they have that too), it’s Nelson’s intermediate and advanced trails that bring those in the know to the hills behind the sunny town.

TOTAL DISTANCE: 58KM 2017

“THE MAMMOTH EVENT HAS BEEN A FIXTURE IN ONE FORM OR ANOTHER ON THE NMTBC CALENDAR SINCE THE EARLY 1990’S WHEN THE EVENT WAS A LARGE 40 - 50KM CROSS-COUNTRY LOOP; THE COURSE KEPT SECRET UNTIL REGISTRATION ON THE RACE MORNING.”

Arriving in Nelson, the relief of seeing our bikes being unloaded from the tin bird was short-lived, and shattered by the wide-eyed, confused look on our shuttle driver’s face, giving us a glimpse into what was about to unfold. Unfortunately, after some miscommunication and a major mix-up we were sent a small taxi to transport our three bikes (there were two of us) and an additional seven large bags (don’t ask) to our accommodation in town. With no taxi vans available in the area, we were left with two options -either load all the gear into multiple small taxis or rent an over-the-top expensive van for the short trip to town. Ordinarily, we wouldn’t need a vehicle in Nelson as, if you’re staying in town, the trails are just a pedal away and within a 15 minute walk you can get to anywhere worth going. So, renting was off the cards. Fortunately for us, a keen airport employee saw our plight and let us in on a hot tip: a public bus would roll in at any minute, it would likely be empty, and for the gargantuan fare of just $3 each we could be dropped to a stop just beside our destination. Sure enough, right on cue, the city bus service came to our rescue in one of their fancy new electric buses and left us with enough money in the coffers to sample some of Nelson’s finest hops later in the day. With a date for the Mammoth Enduro penned in the calendar for 23 -24 March 2024, and a few days free in early spring, it was the perfect excuse to head south on a quick trip to experience some of Nelson’s finest. We weren’t strictly hunting for time on the trails, but for a bit of chilled downtime while not on the bikes too. Chasing some local knowledge, we hooked up to ride with Nelson local and winner of the 2016 Mammoth, Kieran Bennett, and local fast-lady and Santa Cruz NZ representative, Amanda Pearce, as well as total frother, Tayla Carson, Nelson MTB Club’s (NMTBC) event portfolio head.