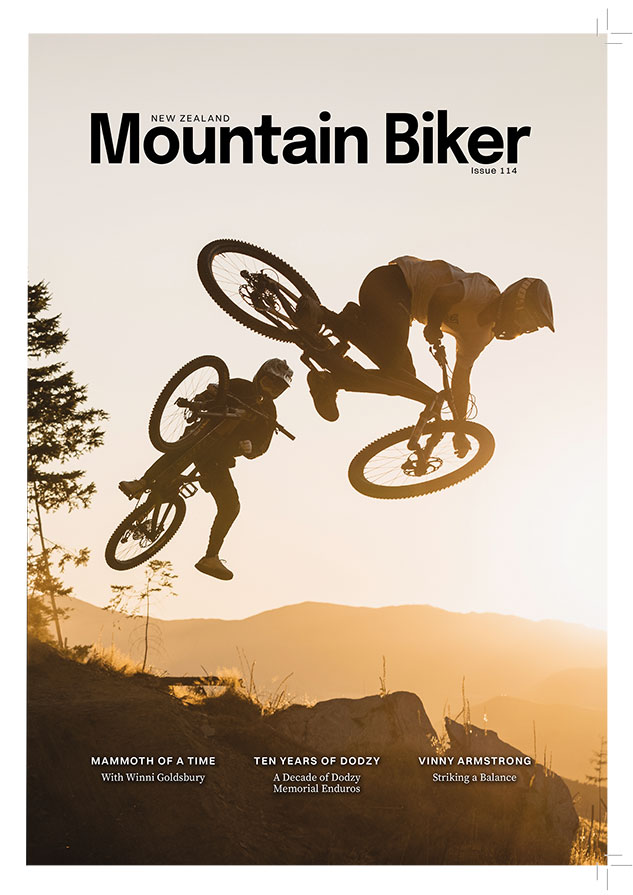

Southern Double Dip

Words & Images Gary Sullivan

We decided to head to the South Island for a holiday because I had just got back from a holiday in the South Island.

I wanted a repeat.

It had been a long five years since we’d last crossed the Strait with our little caravan, and it was an easy sell: Glen is always up for a road trip, and she really loves the West Coast. We booked the first ferry we could get a slot on, hooked up the bach-on-wheels, and hit the road.

That first holiday goes something like this…. Thirteen years ago, a trail was opened that roughly follows a route through the mountains, imagined by gold miners in the 1800s. It’s called the Old Ghost Road, and is a bucket list ride for any keen mountain biker. In fact, it’s such a bucket lister that I rode some of it before it was finished, and could tell back then that it was going to be something special. Nearly everybody I know had managed to organise the time and logistics to get down there, but I hadn’t. Things I thought were more important at the time got in the way. Work stuff, other great rides elsewhere, illness, house building. I just hadn’t got around to it.

Last year, I met up with a friend from Queensland who mentioned he was organising an upcoming junket with some other people. The plan was to do some riding around the top of the South Island, including the Old Ghost Road. I jumped on board.

I met the gang in Wellington the day before we were to make the Cook Strait crossing. John had hired a vintage Toyota Hiace and a trailer for the bikes and bags, which made things simple for me. Get myself to Wellington and ditch my own van at a mate’s place, then relax and ride.

As a bonus, we had time to get a ride in at Makara Peak in Wellington before going south.

I have ridden a bit around Wellington but to my everlasting shame had never made it to Makara, even though it has been in development for something like 25 years. Well, I have now, and it won’t be the last time. It was amazing, and we only dipped a toe in the Makara offering.

The trail builders of Makara hew their routes out of difficult terrain – there is a lot of solid rock to be hacked through. Pedaling out of the main car park, we climbed the sublime Koru trail. It really is a work of art; a climbing trail that is actually fun is a rarity around my way.

Once we reached the summit of the park (which felt like the summit of Wellington), we were treated to massive views, an info station mounted on an outsize bike chain, and even a couple of charging stations for eBikes. I didn’t stick a fork in them to find out, but they looked legit. Just who would cart a charger up there to re-energise for a ride back downhill was not clear, but I guess somebody must.

We took a very entertaining intermediate level run back to where we started, then climbed the thing again via a slightly more taxing route. A few of us took a loop around the high point then jumped on a flow trail back to town. We finished on what some of us reckoned was one of the best bits of trail in our entire trip: it’s called Starfish, and ticks a lot of boxes.

The trip to Nelson took most of the next day, but we still had time to hook up with Mick, a local contact who showed us how to get to Codgers, the trail network closest to town. He led us up another surprisingly pleasant climb to a couple of what Nelson riders consider basic trails. A good way to get oriented, figure out where we were in relation to the riding, and get a taste of the dry and rocky terrain. Back in Rotorua, we have a few rocks in the forest – and we can count them all without having to use our toes. Down here, rocks are everywhere; some are attached firmly to the planet, many are not. In a mellow 18km we still managed an overall up- and-down totaling 726m – that would rank as a big ride back home. Down here, at the ride’s high point, we got a great outlook over town, but also had to crane our necks to look at the peaks behind us, allegedly full of more trails.

There is a mind-boggling selection of riding options down that way, and a couple of days was nowhere near enough to ride even a small fraction of them. We headed out to Cable Bay Adventure Park the following morning. After signing on at a very nicely set up hub, we hooked up with Mick again and crammed 741m of up- and-down into a scant 13km of distance.

We only tackled trails that are tame by local standards, but provided plenty of challenges for me, thank you very much. The first downhill run was called Broken Gnome, and according to my GPS dropped 210m in less than a kilometre. If I wasn’t following a local, I might have chickened out in a few spots but I was already starting to trust the available traction as long as I could stay on the rocks that were firmly anchored. It was steep, and fun. The rest of that ride was a blur, but followed that theme. I have been hearing about a ride near Nelson called the Coppermine Loop for what seems like forever. I was hoping to fit it in while we were stooging around the region. I didn’t expect anybody to suggest doing it late on the same afternoon of the Cable Bay day, but that is what happened.

We headed out at about 4pm. The ride starts with a climb that covers about 20 kilometres at a railroad grade, because that’s what it is. Some 150 years ago, a crew mined Chromite high in the hills behind Nelson, and they used a simple tram line to send the ore down to a depot in town. Horses would pull the empty wagons up to nearly 900m above the town, they would be filled with ore and return using gravity, with a brakeman controlling the pace.

We performed a similar routine, only without horses. And, we used gravity to descend via a much steeper route into a different valley.

The descent into Maitai Valley is half an hour of maximum fun. The trail is dual-use, with signs everywhere reminding you to watch out for walkers. The descent features dozens of beautifully bermed corners which are begging to be railed. There are also lots of rocks. We didn’t see any walkers.

We got back to the motel in the dark, a really big day complete.

Our next destination was Kaiteriteri, a short drive from Nelson and the jumping off point to Abel Tasman National Park. A beautiful spot crawling with tourists and day-trippers, but also hiding a very cool little mountain bike park. Small in area, but with plenty of elevation, it is worth a visit if you are down that way. We started early the next day, to get to the Wairoa Gorge Mountain Bike Park. A visit to this place was another compelling reason to join this junket. It was created, in large part, by a good mate of ours who died way too early. Dodzy was a force of nature, and when he connected, by chance, with a very wealthy guy with an interest in mountain biking, a short-lived phenomenon was born. It’s a whole other story you probably already know, but Wairoa was one of the projects executed by the company formed to develop trails on land the guy owned all over the planet. He moved on from mountain biking, and now Wairoa is owned by New Zealand and leased to the Nelson Mountain Bike Club.

It is probably the most exclusive MTB park in the world. The shuttle-only access to the 70+ kilometres of hand-built trails is usually maxed out at 27 people; the day we visited, there were 18. Two nine-person truckloads of people in a massive slice of forested mountain is pretty much nobody – we felt like we had the place to ourselves. The shuttle is long, and gets riders to about 1200m. The descent is MUCH longer – at the pace I could manage, each run took over half an hour. The trails are graded, and routes have been created using a numerical system to let riders figure out a way down that suits their skill set.

A few of us who rode together, dropped four times – and two hours of riding downhill on fresh trails takes more energy than you might think.

There are three options at Wairoa for accommodation, we were in the largest – a very nice chalet near the base of the gorge. Two other huts higher up look really good too. If you have a gang keen for a weekend away, the Gorge is worth a look.

We tackled the Old Ghost Road as a two-day trip, staying for a night at Ghost Lake hut. There are four huts managed by the Lyell-Mohikinui Back Country Trust which can be booked at the official Old Ghost Road website. There are also two DOC huts, which are first-come, first- served. The LMBC huts are top-notch, and have kitchen facilities with everything you might need except ingredients; there are firebox heaters with wood provided, basic showers, toilets – they are well-insulated and have great locations.

The first day for us was a climb…. 27 kilometres of climbing to Ghost Lake. There is a brief respite halfway up, at Lyell Saddle. We dropped in to the Lyell hut for a snack and a sit-down on the sunny deck, with a huge view over the ranges to the north. A gang of excitable women had chosen Lyell as their first stop on a five- day walk, and they were all either laughing or yelling at each other at once. There were more of them en route, so we were kind of glad to be staying further along the trail.

The highlight of the ride, for me anyway, was the section before Ghost Lake where the trail reaches its highest point at 1344m. Well above the tree line, it sidles along the faces of a ridge, with massive views. We were lucky to have two bluebird days and the outlook from those heights will always be a strong memory of the first day’s ride.

A short drop into the trees brought us to Ghost Lake hut, perched on a ridge and overlooking the distant town of Murchison, where that morning we were buying extra trail food, eating pies and drinking coffee.

I had the foresight to cram a can of beer into my overloaded pack, and I was relieved to find it hadn’t been pierced by anything along the way. I inhaled it on the deck of the hut, feeling extremely fortunate and grateful for everything about the day. It was already cold, and pretty soon it was freezing – literally: when I ventured outside at about 2am for a pee, there was ice on the ground.

John had organised a helicopter drop of food and sleeping bags; the food was freeze-dried and, with the addition of boiling water, turned into something edible. The sleeping bag was absolutely perfect.

Our second day was hard to fault.

The trip from Ghost Lake hut to the finish is 56 kilometres by my count, and descends 1200 metres. There are some seriously cool sections of flowing trail through exceptional forest scenery and I forced myself to stop a few times to look at it. There are also 827 metres of climbing, so it is not an easy day.

The Old Ghost Road was a perfect exclamation point on a quick sampling of the riding in the top of the south.

So perfect, in fact, that I couldn’t wait to do it again. Literally, I could not wait. So I didn’t.

And that is why we headed south a few days after I returned from the first trip.

One of the common themes of the last decade has been a recurring conversation with Graeme, a riding mate. We have talked about riding the Old Ghost Road every summer, and every summer we didn’t get there. Now I had sneaked off and ridden it without him. Another easy sell: we are going down there, we will have a vehicle, let’s get this done.

He signed on, and we set a dateline for the project.

Looking back, it is hard to believe I only got five rides done in a month of wandering around the top of the South, but we were so busy doing bugger-all that that’s all I had time for. Reading books for a start. We try to read books when occupied with normal life, but the luxury of reading one in a single gulp with no stops for any annoying responsibilities is very good. And having a pile of them to get through is even better. We found a reconstituted refrigerator in the main street of Takaka that had become a free book exchange, and we hung around in Golden Bay for a week of bad weather making full use of it.

Loafing along deserted beaches also chopped out extensive periods of time. We are so lucky in this little South Seas paradise, there are so many places that are easy to get to with nobody else in attendance.

Then there are the simple pleasures of doing stuff in a small caravan. Everything takes a bit longer than it does back home. Those are my excuses, but while the rides turned out to be few and far between, they were stellar.

I did a birthday lap of a trail in Whites Bay on our second day in the South Island as a sort of warm up, then spent a few days slacking.

The next outing was another tilt at the Coppermine Loop. The feature of that day, for me, was the feeling that comes with a seemingly endless vista of mountain ranges away to the south of the Coppermine Saddle. There is nothing man-made in view except the trail, and even though Nelson is very close it is hidden and therefore out of mind. It is a ride, but somehow more of an adventure than doing a similar distance and elevation back home.

We visited Kaiteriteri again, had another outing in the great little bike park there, explored Golden Bay between rainstorms, and ended up getting as far south as Hokitika.

The best night of the trip was a simple roadside pull-off, perched on the side of Highway 6, a couple of steps from a wild and windswept stretch of rocks, sand and surf.

My main target for the West Coast leg of the expedition was the Paparoa Track.

We parked up at Punakaiki Campground, an absolute bottler of a place to hang out. Another spectacular beach to explore, Paparoa National Park near at hand, all overhung by massive jungle-strewn cliffs straight out of King Kong.

The campground operates a daily shuttle around to Blackball, where the Paparoa starts. I booked a trip for the following day, and we holed up while the West Coast did what it does fairly often: rain.

The forecast for the next day looked pretty dire, but the day after was not so bad. I switched my booking, and we spent the spare day hiking around in the rain.

When the day arrived, I was up early, packing everything I thought might be needed for a solo ride in remote country. The Paparoa is doable as a single day mission, and that was my plan, but I carted along a pile of food, spares and extra layers just in case it turned into something longer.

The shuttle got me around to the start by about ten. By the time I got underway, it was steadily raining. The rocky trail was drenched. The first ten kilometres is in the forest and, after a short descent, there is a climb to about 1000m that doesn’t let up.

Just before I reached the tree line, I came upon an apparition: two little girls in festive- looking outfits, walking down the trail towards me. They were about six or seven years old by my estimation, and were incredibly cute. One of them politely said, “good luck, you’re nearly there!” I was briefly mystified, but round the next curve was their mother, with an even younger offspring, and carrying an enormous pack. Parenting done correctly.

Soon enough, the trees opened up into the sub-alpine tussock. At about the same time, the clouds lifted, and the first hut came into view.

From there, the trail follows a ridge for what I reckon was the best part of 20 kilometres. It is not easy, constantly rising and falling as it switches from one side of the range to the other; in some places it sketched along the very top of the ridge, only a few metres wide.

Long views back into the Brunner Valley were swapped for expanses of the coast, as the trail stitched a course along the spine of the Paparoa range.

The eventual descent through cloud forest and down into the rainforest below was a highlight of an amazing day. Threading its way down through huge boulders, waterfalls, and crossing a really cool swing bridge, the trail becomes an easy run through some regenerating forest following the Punakaiki River. The final sting in the tail comes with five kilometres to go, a steep little climb that is relieved by the beauty of the forest it clambers through.

We spent a couple of days getting ourselves up to the amazing Gentle Annie campground on the north bank of the Mohokinui River mouth, handy to the end of the Old Ghost Road.

A fairly simple logistical exercise was then executed: I met up with my mate Graeme at Westport, and we drove up the Buller Gorge to the start of the OGR. We ditched the van there, depositing the keys in a locker box for the very accommodating Buller Adventures team to collect and deliver to the other end of the ride.

Our first day on the OGR was a mirror of the ride I had done a month earlier, with the added feature of some constantly mobile clouds in the valleys making the vistas from the tops even more interesting.

Our night in the Ghost Lake hut was entertaining; it was almost at capacity with an even split between riders and walkers. The main topic of conversation was the weather – the cloud closing in as darkness fell looked ominous, but a young fella doing the ride with his parents assured us that if we could get through to the end before 2pm the next day, we would be dry.

Graeme went outside at 2am and came back in to report that it was pissing down.

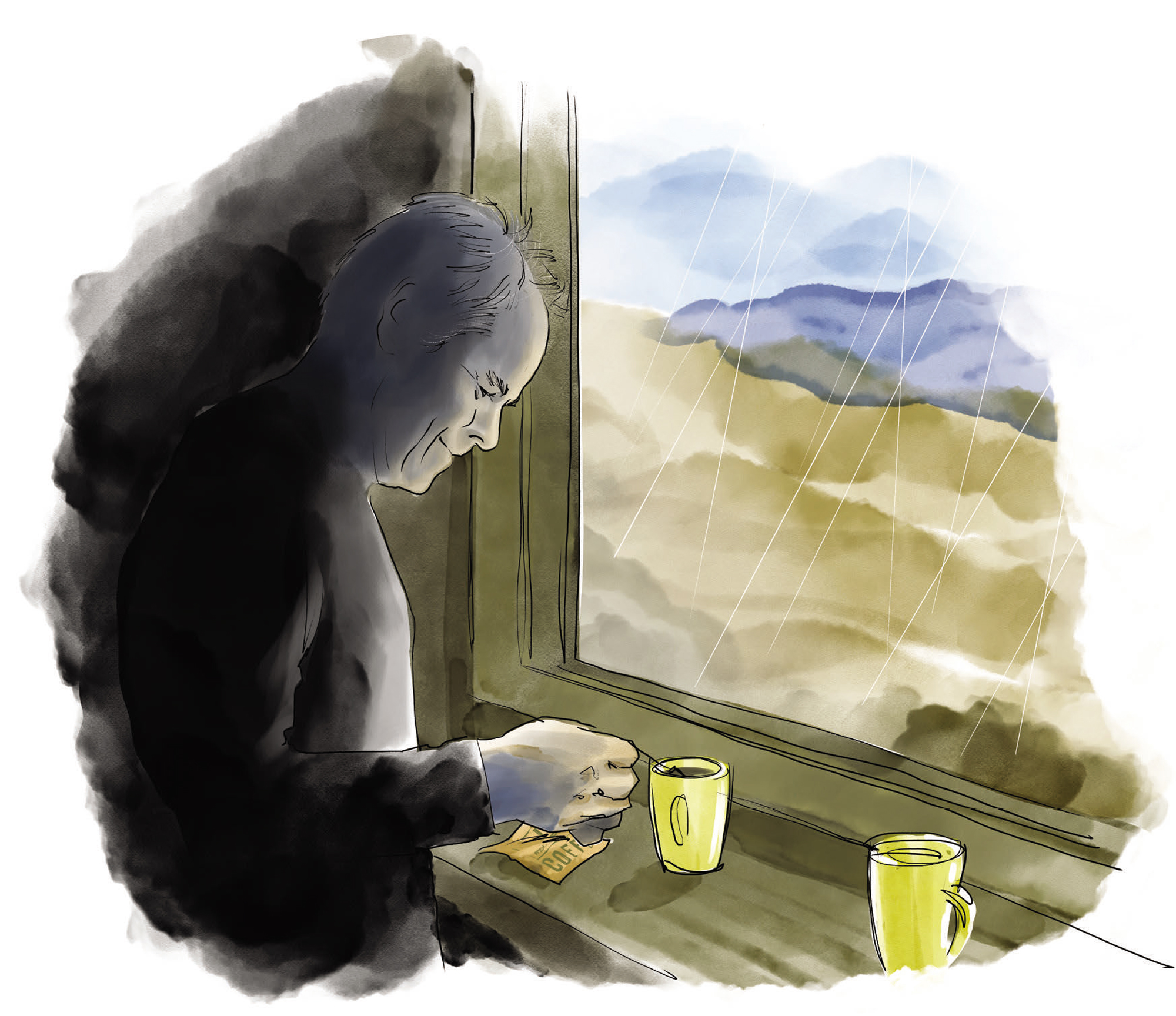

The dawn was grey and wet. We had a slow start, lingering over coffee while we peered out into the gloom, but eventually it was time to go.

As soon as we were on the trail, the weather became irrelevant. The look of the place was completely transformed. Shifting cloud exposed glimpses of the terrain, just enough to confirm we were on an exposed spine with dramatic spaces below.

After clambering down the very awkward stairs, the ride through the forest was so different to my previous trip that it was like a strange new planet. Everything was wet. Water was everywhere, running down small courses and across the trail, dripping off every element of the forest, and completely soaking us. The trail can handle it, rain is a regular part of the west coast and everything that can be washed away probably already has been, and the rocky trail was never a problem.

In the entire day of bucketing rain the bikes ran like clockwork. At a riverside stop for refueling, we noted how amazing mountain bikes have become. Everything worked, gears shifted, brakes slowed us down, suspension floated us along, seat droppers dropped and returned to their original position. We swapped recollections of bikes that ceased to function on days like this.

Somehow, the weather put an extra layer of meaning on the day. The ride seemed much longer than the dry version, and just as memorable. The van was waiting for us in the carpark at the trail terminus, and I backed it under the little shelter so we could get into some dry gear and pile the dripping carnage of the day into the back for the run back down to Westport with the heater going full blast.

I dropped Graeme off and headed back up to Gentle Annie, where I had a long and very satisfying shower.

I consider myself very fortunate. Besides winning the life lottery of being born in Aotearoa, I have managed to ride my bike in some cool places around the planet. I can honestly say, the opportunities we have here at home are as good as anywhere else I have been.

Cole Lucas: Perfect Storm

Words & Images Riley McLay

Sport can be glorious, but it can be equally as cruel. The constant adversary of staying at the top level, let alone reaching it in the first place, can become a sport in itself.

In a short period, Enduro racer Cole Lucas went from being a household name among the top ranks in Enduro to not having a professional ride for the 2024 season, ultimately leading to his exit from the EDR circuit entirely. A perfect storm of injury battles, economic struggles within the industry, and a race series in a state of limbo had created a challenging environment for racing success. Once celebrated as the exciting new frontier of mountain bike racing — with thrilling spectacles on some of the most beautiful trails in the world — now feels so much like the ‘awkward cousin at the wedding’ that even new race organisers don’t know what to do with. This shift is particularly surprising given the thriving grassroots movement and Enduro’s status as the most accessible racing format, which best captures the essence of a great day out on the bike. This uncertainty has led many racers to take a hard look whether the time and resources they invest will be worth it.

Cole’s introduction to push bikes started with humble beginnings, chasing his two older brothers down the local BMX track in his hometown of Hamilton. Naturally, this led to race plates being slapped on at club races, where Cole could prove once and for all who ruled the roost at the dinner table. While his relaxed yet competitive personality thrived in the racing environment, Cole had his sights set on bigger things. The BMX was eventually traded in for a dirt jumper, and weekends were now spent at shuttle days in the Rotorua Redwoods. Even with just one brake, the dirt jumper wasn’t going to hold Cole back. He had caught the downhill bug. “There was always a good crew to ride with, and we loved to push each other. There was no place I’d rather spend my time at that age” says Cole. In one of Cole’s very first downhill races, he secured second place in the under-15 category at the Oceania’s in Rotorua, proving that he could transfer the skills he’d honed on the BMX track to this new discipline. Multiple NZDH rounds followed, where Cole would dominate for a majority of his years in the junior ranks. This was matched by strong results at both National Cup rounds and National Championships. He was no longer chasing his older brothers but had found himself amongst the pointy end of some of the top talent coming out of New Zealand. Racing support was difficult to find in his junior years, but Cole received backing from development teams put together by 3 Sixty Sports and Wide Open, who recognised his talent. Working part-time for his family’s roofing business — and their support — also helped fund his racing aspirations and provided the flexibility to fit in training and bike time.

Cole was given the opportunity to represent New Zealand at the Junior World Championships in Vallnord, Andorra, in 2015. This was Cole’s first taste of international racing, and he made the most of the opportunities by gaining valuable experience and competing in several World Cup rounds across North America and Europe in the lead up. In just his first year in the junior category, he achieved a flurry of top-20 results, culminating in a 23rd place finish at the World Championships. During this time, fellow downhill racer, Eddie Masters, also saw the potential in Cole, taking him under his wing and helping him navigate the World Cup circuit. Eddie’s role as team rider/team manager allowed Cole access to the Bergamont team pits and the odd bit of technical tweaking from team mechanic and fellow Kiwi, Kurt McDonald. The privateer life isn’t always the optimal environment for consistent results, however, witnessing other Kiwi’s getting the job done on the world stage with what they had to work with was empowering for Cole. Even more so was the camaraderie, as fellow Kiwis understood the commitment to time, training, and resources required for success.

Although Cole had always focused on downhill races, he also had a passion for trail riding, which was often incorporated into his training. The growing popularity of the Enduro World Series (EWS) had caught his attention – now not just racing for retired downhillers, but as a competitive series to further build upon his racing skillset. During a break between World Cups in 2016, Cole decided to give an EWS round in La Thuile, Italy, a go, where he surprised even himself by finishing 13th in the under-21 category. “Enduro felt just like my training; going out for a day of riding with a good crew, but we were riding some of the best trails in the world,” says Cole. The following year, he competed in several more EWS rounds, securing a podium spot with a 3rd-place finish at his home race in Rotorua, as well as at the Carrick round in Ireland. Cole backed this up by qualifying for his first-ever World Cup race in the elite category. Unfortunately, the following week, a crash in Leogang, Austria forced him to return to New Zealand for surgery, causing him to miss the rest of the season. Cole reached a turning point in 2018 as he grappled with the challenge of qualifying for downhill World Cups. Already a consistent threat in EWS rounds, he shifted his focus toward the overall. This move paid off with an impressive 3rd place finish. The advantage of staying in the under-21 category in Enduro, compared to being pushed out of the under-19 junior category and into the increasingly tight times of the elite field in downhill, worked in Cole’s favour and allowed him more time to adapt and flourish in the Enduro format. He found continued mentorship from downhill racers Eddie Masters and Matt Walker, who were also shifting their careers toward Enduro racing. Cole tagged along with the extended Pivot factory team, who hooked him up with a frame and pit support at races. Although many riders were increasingly leveraging their own social media following to promote themselves and the brands that support them, Cole was determined to let his results speak for themselves.

Cole’s impressive momentum continued in the Open Men’s field. With the support of the newly established NZ Arapi Enduro Team a New Zealand program created by Brendan Clarke to provide better opportunities for Kiwis to compete in the EWS — he secured two top-10 finishes and one top-20 finish in 2019. His arrival to the top ranks of EWS didn’t go unnoticed, and by the end of the season, he was offered a contract to ride for Ibis Factory Racing. “It was honestly a dream come true. I had been working towards it my whole life, and after doing it for so long, I was over the moon that it had finally worked out,” says Cole. All of a sudden, Cole found himself whisked away to a team camp in Italy, where he was focusing on fine-tuning bike settings and race strategies. Gone were the days of sleeping in vans and using ‘set and forget’ bike setups. Even though Cole would admit he was very green to being a part of a factory team, he found a whole new perspective to racing that he was keen to implement. That was, until the world stopped. Only a stone’s throw away from where the camp was situated, the very first cases of Covid-19 appeared in Italy. Cole found himself back in his flat in Rotorua, under quarantine and waiting out the lockdown with the rest of us. Despite the disruptions to daily life in 2020 and 2021, EWS managed to continue racing. Cole grew frustrated with a slump in results, feeling they fell short of his expectations. However, the team still never pressured him. Instead, their unwavering support allowed an environment for him to grow as a racer.

Ibis team manager, Robin Wallner, masterminded a new Enduro-specific training regimen for Cole and, with a move to Queenstown, closer to quality trails and training partners, he put himself in the best position for success. Knowing it was time to put his mark on the circuit, Cole came into the 2022 season firing with six straight ‘top ten’ results. Everything was clicking. That was, until he broke his knuckle causing him to miss the next round in Switzerland. With only one round remaining in Loudonville, France, his overall standing had dropped to 8th. Desperate times called for desperate measures. Cole taped his broken knuckle, which just happened to be his left braking finger, to a splint and attempted to race the final round. The pain was unbearable, and he was forced to withdraw, slipping further back to 12th place overall. Even though it was Cole’s best overall season result, he couldn’t help but think about what could have been; but he felt relieved his speed was there. Unfortunately, Cole’s injury troubles continued after returning to New Zealand where, whilst out training, he suffered a fractured spine and a concussion. Just when he thought he was out of the woods and back on track, he misjudged a berm while riding in the Queenstown Bike Park, resulting in a Grade 3 shoulder separation. Suffering this injury just weeks before the season opener in Tasmania was far from ideal, but Cole was determined to push through and deliver a result. Although he managed to get through the majority of the first day of practice, a crash on the final stage forced him to withdraw from the race. This string of injuries was a “huge kick in the guts” and wasn’t helped by a series of crashes, mechanicals and poor results throughout the season.

2023 saw the EWS integrated into the UCI calendar, establishing the UCI Mountain Bike Enduro World Cup (EDR). The new organisers, Warner Brothers/Discovery, did not inspire confidence in the new race series. This was evident through a reduced number of rounds, poor communication and promotion of events, and a perceived attitude that EDR was meant to play second fiddle to its downhill and cross- country counterparts. This uncertainty spread throughout the industry as, along with economic pressures following Covid-19, bike brands were forced to reassess their marketing strategies, particularly their ability to support race teams. As expected, rumours circulated rapidly and, like dominos, brands announced they would be withdrawing support from the EDR. Still a surprise to Cole, he was informed mid-season that Ibis Factory Racing would too be dissolving at the end of the 2023 season. Being a contract year and having a down season results-wise created the worst timing possible. After reaching out to several brands, including major household names that were significantly scaling back their current operations, Cole was forced to announce that he would not be racing in the EDR for the 2024 season. The financial costs to return as a privateer were just too great, contrasted with too much unknown of how, and even if, the series was going to continue into the future.

“Absolutely gutted” Cole took the time to step back from racing and reflect on his achievements, now looking toward a life not revolving around racing. He understands better than anyone the dedication and effort required to reach the top level of the sport, and he’s come to terms with the fact that sometimes things just don’t go as planned. Cole is deeply grateful to those who helped him reach where he is today and is excited to still enjoy the hobby that has given him so much. He’s also looking forward to working with Zerode, a Kiwi brand he feels he has grown up with, and to compete in a series of local races, including the inaugural New Zealand Enduro Series. Taking things as they come, while aiming to have as much fun as possible.

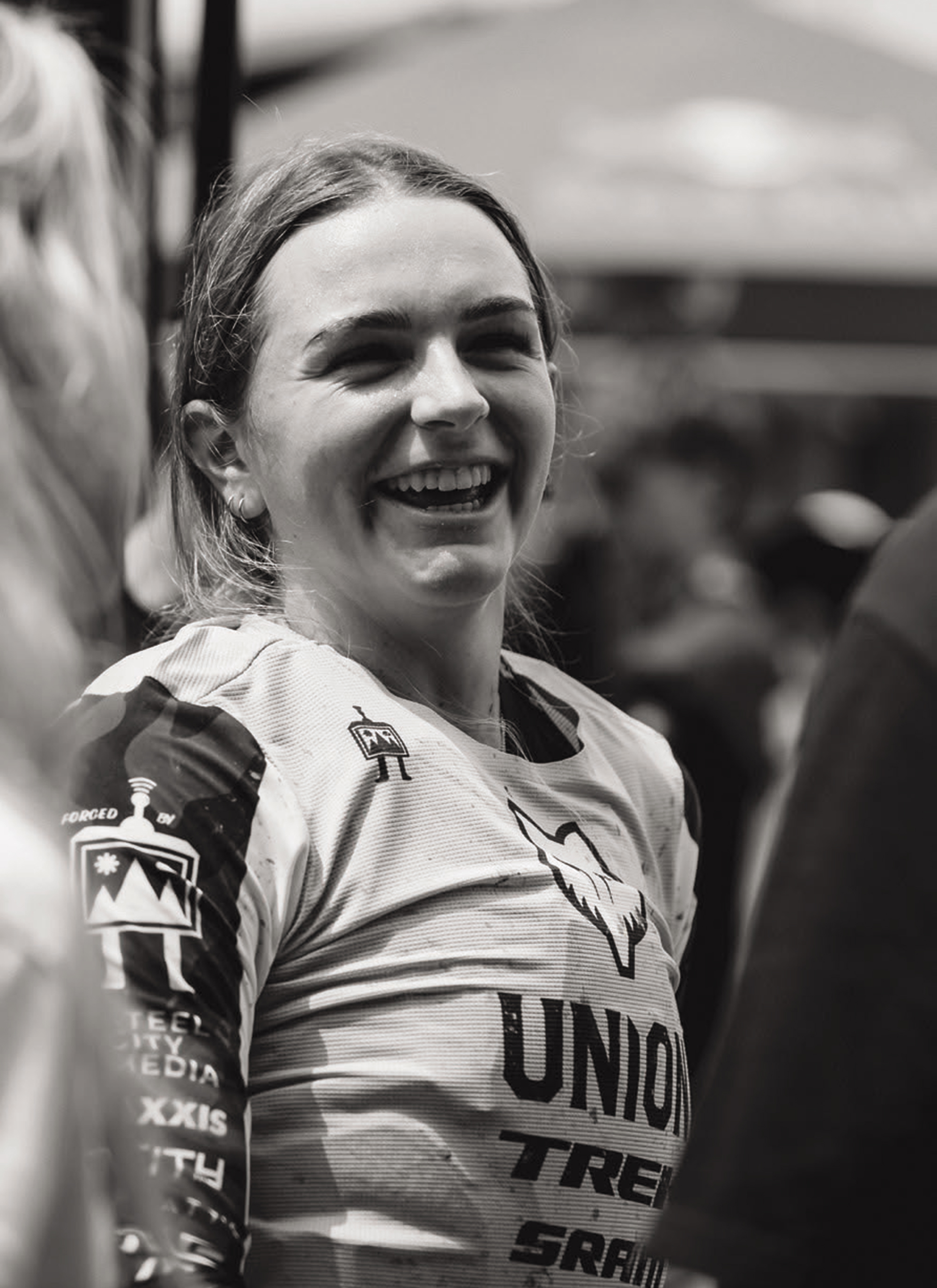

It's Ellie Hulsebosch but who's the boss will do

Words Lester Pery

Images Cameron MacKenzie

At just 16 years old, Ellie Hulsebosch has chosen the path less trodden, in a quest to dominate downhill racing. For the next few years, she will opt for less school and more sport, working to complete her schooling while travelling the world, chasing her dreams.

She makes no secret of wanting to be the best, inspired by ex-world champ and fellow Bay Of Plenty resident, Vanessa Quinn. Seeing Vanessa out on the trails and knowing her history, Ellie was all ears when Vanessa offered up any tidbits of advice: “To be the fastest girl, you have to be the slowest boy” was one such quip, motivating Ellie to ride with her brother and his mates. Ellie points to Rachel Atherton as an inspiration in this vein, a strong woman riding with a host of the fastest guys around: her brothers.

Brought up in a tight-knit, supportive family, Ellie acknowledges their input in helping her push through the hard times to keep progressing towards her goals, no matter what she’s going through. While growing up in Tauranga, Ellie and her family got stuck into all sorts of outdoor sports, but after a stint of motocross, she eventually picked up a Canyon Spectral and took to mountain biking, “because Mum could do it too”.

Keen to satisfy her competitive spirit, Ellie jumped straight into racing. “My first downhill race was in late 2019, for Crankworx in Rotorua. I remember walking the whole track, getting a 7-minute time on a 3-minute track, and being smoked by all the other girls.”

Through 2020, Ellie dabbled in some Enduro racing, winning two rounds of the 2w Gravity Enduro. Then, through 2021, she switched focus to the NZ National Downhill Series, trading blows and podium positions with Erice Van Leuven and Sacha Earnest throughout the season. It wasn’t until November 2022 that Ellie broke cover and launched herself into the limelight with a win in the U17 category at the 2022 Crankworx Rotorua Taniwha Downhill, in a time that put her third fastest woman overall on the day.

By late 2022, she was firmly focused on dominating the downhill game, and got serious about training heading towards the 2023 season. A clean sweep of the summer National DH Series under 17 division was a massive boost of confidence. Unfortunately, her luck ran out on her final run at National Champs, Coronet Peak, in late February. A crash resulted in a stable compression fracture to her T5 vertebrae and ligament damage to her thumb. Fuelled by adrenalin and close to the finish line, she managed to pick herself up and break the timing beam in second place. She finished her NZ season with a National Series win, a silver medal at NZ champs, and some time off to let her body heal before jetting to Europe for her first stint of international racing later in the year.

“Verbier was the first race, and it was my favourite; the track was proper as well.” Straight to the podium’s top step in Verbier was the perfect way to begin her international career. A couple of races followed at Schladming, an iconic World Cup venue that was visited for two back-to-back races. “Schladming was really fun, but they had tapped off all the hard lines, so there were a lot of corners. I wasn’t too happy with how I went there, so as soon as I arrived home, I signed up for BMX.”

Wrapping up her time in Europe at Bellwald, Switzerland, Ellie won the Open division and was the fastest woman down the hill that day. Although she was on the other side of the world in foreign territory, Ellie had become a podium threat at every race she attended, and heads were turning.

In late 2023, Ellie had an email from Joe Bowman, owner and manager of the Union team, and over a few months, a deal was struck that would see Ellie join them for 2024. Joe gave us some background to Ellie being selected for the team: “We’ve always had a soft spot for Kiwis, and I think the whole Union ethos kind of fits helping out people from New Zealand and Oz, because you guys have it a lot tougher, coming over to Europe to race and being away from home so long, that you need a good level of support even to give it a go, let alone to actually try and race at the top.”

“I’ve always kept an eye on Kiwi national results because of Lachie (Lachlan Stevens-McNab), Tuhoto (Tuhoto ariki Pene) and Finn (Hawkesby- Browne) back in the day, and always saw Ellie’s name popping up at the top, through youth categories. When it got to the middle of last year, it was tricky times because we’d lost a bunch of sponsors and money and didn’t really know what was going to happen with the industry. But, at the same time, you’ve got to keep moving on. And we needed to fill a gap and wanted to get a junior woman. Ellie was obviously on the list. I’d also started to hear from a couple of other people about her. Sven Martin mentioned her and actually sent a message on Instagram that I never got until after the fact, that’s pretty funny. That says a lot. And I think just looking at the margins she was putting into people and where she was stacking up against the elites and juniors at Kiwi nationals, kind of said enough.”

After the industry took a dive post-COVID, Joe scrambled to secure new sponsors and funding as The Union headed toward the 2024 season. He couldn’t promise what gear they’d be using, but he was confident the puzzle pieces would fall into place on time, and they did. For 2024, The Union had a complete shake-up regarding their gear, eventually signing to ride Trek frames and Sram/Rock Shox components while decked out in Fox apparel. It was go time!

Joe continues, “I’ve been stoked character-wise. She’s a funny one. She’s kind of a mix of this super confident, smart young woman who’s crazy mature for her age in some ways, but then she’s also definitely still a kid, a teenager, and deals with all the usual stresses of racing and definitely has had some nerves creeping in, which have affected a few races. Just normal racing stuff. She is super smart and loves a yarn!”

Beginning the 2024 NZ season with National Series wins at Whangamata and Rotorua; things came crashing down in Christchurch during round three. A crash in the infamous rock garden while racing “The GC” left her sidelined with a broken knuckle and injured hand. Considering the consequences of crashing in that section, Ellie was glad to come away relatively unscathed and able to continue to fight for the remainder of the NZ National Series.

A sturdy strapping job and some painkillers helped her battle through the Cardrona National series round for round four, once again racing to the top step of the podium. A week later, she backed up that performance to win the National Championships at Coronet. A hard-fought race on a “one-dimensional” track was not one of Ellie’s favourites; she got the job done despite carrying her injuries from only two weeks earlier.

Crankworx Rotorua began Ellie’s journey into Downhill racing. By March 2024, she had gone from walking the track just four years earlier to walking to the podium, taking the overall women’s downhill win on Rotorua’s famed Taniwha downhill track.

With the NZ summer coming to a close, hours in the gym banked, sprints ticked off, a National Series overall win, a National Championship title, and armed with all the tools she needed to succeed thanks to her new team, Ellie set her sights on the World Cup Series and headed to Europe.

Ellie’s debut on the World Cup stage was the Fort William, Scotland opening round. Initially unsure of what to expect, her apprehension disappeared once she arrived at the venue and got stuck right into the thick of things. “Everyone is actually really nice and not nearly as big as they seem on TV, so it’s been pretty cool to talk to people who I look up to, and have them help me out — everyone in the scene is so nice.” She delivered a strong performance despite the challenging conditions. The notoriously rocky, wet, and foggy course can be a brutal monster to tame. Although leaving with third place was not what she wanted, it was a great start to the season.

After that solid start, Ellie headed to Bielsko Biala, Poland, for round two. Conditions were difficult, with wet and wild weather impacting the course and making for unpredictable and difficult-to-read track conditions. Despite her best efforts, Ellie didn’t have an ideal day, falling just short of the podium, under a second back from Kiwi compatriot, Sacha Earnest, who was third.

Another wet and unpredictable track greeted racers to round three of the World Cup Series in Leogang, Austria. A first-place qualifying run banked her solid points for the overall series standings but, like most, Ellie had some bobbles in the steep wooded sections during her finals run, rodeoing her way through the first steep section with both feet off. All was not lost, and even after nearly going over the bars, then getting off line and all but stalling out on the second steeps, she regained composure and got back on the pedals through the wide- open lower sections, finishing second behind Lower Hutt shredder, Erice Van Leuven.

Jumping back over to Italy, Ellie lined up for round four of the World Cup. Val Di Sole’s “Black Snake” course has a reputation for being one of the most challenging and physically demanding courses on the UCI World Cup circuit. The track is four and a half minutes of mayhem, requiring racers to deliver both physically and mentally, putting the risk and pain of the effort out of their mind to deal with the high-speed, technical course. In a pre-season interview, she voiced that the “Black Snake” of Val Di Sole was one of her favourite tracks, foreshadowing events to come. On June 15, 2024, Ellie stamped her authority on the sport with her maiden World Cup win, cementing herself firmly as one to watch for the future.

“There have only been highs this year so far. Things definitely haven’t gone the way I wanted them to sometimes, but I have been learning to make the most of every situation — take the positives and use them to grow — which has really helped when life throws obstacles at you…. which does happen a lot when you are flying down a hill!”

As you’d imagine, racing overseas is not a walk in the park for Ellie as she comes to grips with the pressure and stresses of racing on the world’s biggest stage. “The first few races (of 2024) were pretty hard, just getting really nervous, not eating and, for almost every race, my GoPro (from practice) was faster than my race runs. So I knew what mentally needed to change, and it was just trusting the process and remembering all the work I had done. At Val Di Sole, I just mentally felt good, as well as on the bike. I was starting to ride like me again after working on some stuff in the break between races, so it all came together.”

Round five of the 2024 World Cup saw the circus head to Les Gets in the Haute-Savoie region of France, an iconic, fast and technical track that Ellie would typically thrive on. During an early practice run, she misjudged her speed into a corner in the top sector of the track, ejecting herself over the back of the turn. The resulting yard-sale could have easily taken her out of the race before it even began. With a battered body, she had a slower build-in pace towards her final run than she would have hoped, but she was confident the speed would come when the time counted.

Qualifying on a mediocre run, feeling optimistic for a strong performance, she knew she could tidy things up and find more pace come the finals run. Frustratingly for her, the Juniors race was cancelled after heavy storms hit the area, leaving a saturated and slippery track deemed unsafe to race by officials. Ellie and fellow juniors had to settle for their qualifying positions as a final finish, leaving her in third.

“I think the hardest part has been not having my parents at all the races; they have always come to all my races and helped me, even just having a laugh or when I need a hug.”

Before the World Cup racing kicks off again after a nine-week summer break, Ellie will head to Pal Arinsal/Vallnord, Andorra, to take on the World Championships at the beginning of September. The 2024 Champs will be Ellie’s first visit to World Champs. Following the 2023 Junior Women’s podium sweep by the Kiwis, there’s quiet confidence around the scene that the Kiwis will once again be battling for that top step, and Ellie’s name is firmly in the mix as a contender for the win.

“I love training just because the harder you work, the luckier you get, and no matter what happens, no one can lie about that; if you don’t give up, it will show. It’s also my way to still get benefits but also to have a rest from biking and clear my head.”

With two rounds remaining, Ellie leads the 2024 World Cup at the time of writing. Fellow Kiwi, Erice Van Leuven, is a scant 10 points behind her, and the UK’s Heather Wilson is just another five points back; the season is still wide open, and we’re expecting fireworks come early September in Loudenvielle, France, and the final round at Mont-Saint-Anne, Canada, a month later.

What does the future hold? Well, it seems even Ellie isn’t entirely sure. “For now, I am going to focus on riding my bike and doing well as an athlete and see what opportunities open up for me, and we will see where I go from there.”

During a pre-season training camp, while answering questions on how her surname is pronounced, Ellie grinned and replied, “Ellie Hulsebosch, but Who’s the Boss will do”. This single sentence showed so much about her character, aspirations, and confidence. One to watch for the future, for sure!

Down in Durango

Words Liam Friary

Images Cameron MacKenzie

URANGO, COLORADO, IS A TOWN STEEPED IN RICH HISTORY AND VIBRANT CULTURE. ORIGINALLY ESTABLISHED AS A MINING TOWN IN THE LATE 19TH CENTURY, DURANGO’S PAST IS STILL VISIBLE IN ITS WELL-PRESERVED VICTORIAN ARCHITECTURE AND THE NARROW- GAUGE RAILROAD THAT ONCE TRANSPORTED PRECIOUS METALS FROM THE MOUNTAINS. NOWADAYS, HOWEVER, THE TOWN HAS EVOLVED FAR BEYOND ITS MINING ROOTS TO BECOME A MECCA FOR OUTDOOR ENTHUSIASTS, PARTICULARLY MOUNTAIN BIKERS.

Outdoor lifestyle culture is second nature to its inhabitants. The biking culture, in particular, reached its peak in the 1990s when Durango played host to several high-profile mountain biking events. During this era, the town produced and attracted legendary riders like John Tomac, Ned Overend, and Missy Giove. These athletes not only put Durango on the map in the mountain biking world, but inspired a generation of riders and helped shape the town’s identity as a premium biking destination. These days, many mountain bike pros and outdoor athletes of all types either reside in, or come to train in, Durango.

What truly sets Durango apart is how deeply the cycling culture is embedded in the town’s day- to-day life. The hospitality extended to riders is remarkable, with the town fully embracing its reputation as a biking hub. This acceptance is visible everywhere you look — bike racks are ubiquitous, and cycling paraphernalia adorns the streets. Whether you’re grabbing a coffee, enjoying a meal, or having a drink, you’re likely to spot bike-themed decor or fellow riders pedalling down the street.

The backcountry surrounding Durango is nothing short of spectacular, offering an extensive network of trails that seem endless. The high- altitude terrain above the tree line presents both a challenge and a reward, with lung-busting climbs leading to breathtaking alpine views.

My arrival was delayed by one day due to an issue with the plane’s exit door at my departure airport (Calgary). I didn’t complain — I’d much rather have door problems on the ground than in the air! Upon arrival, the airport reminded me of a regional airport in New Zealand, instantly making me feel at home. The landscape featured high desert terrain surrounded by endless mountain vistas. During my Uber ride into town, I noticed the countryside was dotted with large ranches, big barns, and hefty pickup trucks. The historic town itself matched this character, boasting beautifully restored brick buildings from bygone eras.

I checked into The Leland House, which is a building dating back to 1927 and considered one of Durango’s historic landmarks. It has been lovingly preserved to maintain its vintage charm while offering modern amenities. This boutique hotel is in the heart of downtown Durango, with Lola’s Place just next door, which hosts a variety of food and drink vendors in a laid-back environment. This spot provided the ideal base for my stay in Colorado’s Southwest. A week in town provided ample time to get a handle on Durango and its offerings. To shake off the travel fatigue and acclimatise to the higher altitude, I opted for in-town riding. This taster also gave me an understanding of the terrain I’d encounter further afield. Durango boasts multiple MTB parks in town, including the new Durango Mesa Park, Horse Gulch, Twin Buttes, Overend, and Animas. All of these are accessible and rideable from downtown, where my accommodation was based. A few hours of riding can cover a significant number of trails in this extensive network.

Travis Brown is a legendary figure in the world of mountain biking. A professional cyclist since ‘91, Brown has left an indelible mark on the sport through his impressive competitive career and ongoing contributions to bicycle technology. He’s best known for representing the United States in the 2000 Sydney Olympics, but has also claimed multiple national championships in both cross- country and marathon disciplines. Beyond racing, he’s been instrumental in product development for Trek Bicycles, helping to innovate and refine mountain bike designs. His expertise extends to bikepacking and ultra-endurance events, further cementing his status as a versatile and respected figure in the cycling community.

I exchanged a few messages with this local legend, and we agreed on a location for a bike drop-off. I would be riding the new Trek Top Fuel for the duration of the trip, which seemed like an adequate fit for the pedal-friendly terrain. While I had previously met Travis in digital realms, this would be our first in-person encounter. He’s a good dude; our conversation flowed instantly, and he was eager to show me around his beloved hometown of Durango. Brown’s passion for the sport, and intimate knowledge of trail systems —particularly around Durango—make him an invaluable resource for both recreational riders and aspiring professionals. I wasn’t familiar with all the riding zones he mentioned, but I quickly learned about them. By the time our conversation ended, I was thrilled about the rides ahead of us.

The first local ride was a few afternoon hours in Mesa. The pedal from town was short—in fact, just three minutes—before I hit the singletrack climb. Durango town soon lay below as I climbed further into Mesa. An open meadow offered panoramic views, and I took the time to take everything in while sipping water, as the day was quite warm. Turning around, I spotted the Animas mountain range on the other side of town, encapsulating it. The bike proved to be the perfect portal for exploring a new location, allowing me to take in all my surroundings relatively quickly but still at a human pace. I pedalled up the trail and dropped into a new flow/jump line. This was the ideal opener for me to gain confidence with the bike and terrain. I lapped a few more similar trails before heading back to town for a quick shower and dinner.

At dinner I met up with Travis, his wife Mary, from Durango Trails, and Rachel Welsh from Visit Durango. The restaurant atmosphere was nice and relaxed as we talked about the riding history, culture, and development in Durango. The story behind Durango’s extensive riding networks is really about trail advocacy and passionate people, such as Mary and Travis plus countless others.

Durango Trails is a non-profit organisation dedicated to planning, building, and maintaining the extensive network of multi-use trails in Durango. Founded in 1989, this volunteer-driven group has been instrumental in creating and preserving over 500kms of sustainable trails in the area. The organisation works closely with land managers, property owners, and the local community to develop and maintain a diverse range of trails suitable for hikers, mountain bikers, equestrians, and other outdoor enthusiasts.

Durango Trails is known for its commitment to sustainable trail design, which minimises environmental impact while maximising user enjoyment. Their efforts have significantly contributed to Durango’s reputation as a world- class destination for outdoor recreation, with mountain biking at the forefront. The organisation also focuses on education, hosting workshops and events to promote responsible trail use and foster a sense of stewardship among trail users.

The following morning was filled with coffee and breakfast burritos — which became the staple for most mornings thereafter. Travis rode over and offered to show us around Twin Buttes MTB Park. Twin Buttes is located on the western edge of Durango. This trail system offers a diverse range of riding experiences, from flowy singletrack to more technical terrain, catering to riders of various skill levels. The area features approximately 30kms of purpose- built trails winding through pinon-juniper forests and open meadows, providing stunning views of the surrounding landscape.

On the way to the trailhead, we discussed our plans for the next few days, keeping things flexible due to the weather forecast. I visited in late June, which typically marks the beginning of summer in Durango. While the weather should have been more settled at this time, afternoon thunderstorms were prevailing — a pattern more characteristic of July. This meant any high-country excursions would need to be tackled early to avoid the risk of getting caught out in a storm.

Twin Buttes offered some superbly cut singletrack weaving through desert scrub, a landscape characteristic of the lower elevations and more arid regions surrounding the town. Durango’s landscape is a tapestry of ecosystems, with desert scrub painting the lower elevations in muted greens and greys. This hardy vegetation, a hallmark of the Four Corners high desert, thrives in the semi-arid climate. Sagebrush and rabbitbrush dot the terrain, their silvery leaves a stark contrast to the vibrant red soil. Prickly pear cacti add splashes of green, their pads like nature’s armour against the unforgiving sun. As the elevation rises, piñon pines and junipers emerge, their gnarled forms creating a transition zone known as piñon-juniper woodland. This vegetation not only provides important habitat for wildlife but also contributes to the unique aesthetics of Durango’s mountain biking trails, especially in areas like Twin Buttes.

The pedal up was out in the open, which was hot even in mid-morning. Once we gained elevation, we were rewarded with a better perspective of the diverse and expansive landscape we were in. The descent offered a fun, flowy, well-bermed trail, scattered with a few rocky technical sections. The elevation didn’t drop off suddenly, which made for good, fast pedalling sections between descents. I was starting to become accustomed to the Trek Top Fuel and welcomed its superb pedalling ability. Lunch was Mexican food – authentic street-style tacos. I rested in the summer sun as a big afternoon was on the horizon.

The heat was soaring and I still hadn’t really acclimatised to the altitude but, with limited time in town, the more riding the better – right?! Travis rolled over and lead the way to Overend Mountain Park, named after Ned Overend. Ned is another famous MTB local from this small biking town. The trail system consists of about 30 km of interconnected single-track trails. These trails wind through ponderosa pine forests and offer views of the surrounding landscape. The trails vary in difficulty, ranging from beginner-friendly to more challenging routes for experienced users. It leaned more towards old school MTB trails, with an XC flavour and a heap of up and down and swift sections. This soil was a little looser and didn’t offer as much grip as the other MTB parks around town. I was bloody blown as the second ride, heat and altitude got to me. I managed to nurse myself home, have a cold shower and sit on the sofa with the air-con blasting. I now had a very good lay of the land and the proximity of MTB parks that surround Durango.

The backcountry on offer is extensive and endless. I’m super energetic and wanted to cover as much high country as possible, but the reality is that I couldn’t do it all in one week. Not to mention the weather was another factor, with thunderstorms forecast. Travis was glued to weather reports and local weather guru’s and, thankfully, it looked like there would be a few days we could venture into the high country. Travis swung by in his Dodge van early the next morning. Breakfast burrito, coffees and yarns filled the hour transfer to the trail head. I opened the door of the van and could already tell the air was thinner. This was Coal Bank Pass trailhead, which sits at 3,230 metres.

Our ride would tackle the Engineer Mountain Trail located in the San Juan National Forest, about 55kms north of Durango. It’s known for its stunning views, challenging terrain, and the distinctive peak of Engineer Mountain that serves as its namesake and ultimate destination. The climb was just over 5km with an elevation gain of 600 metres, so we’d tick over 3,500 metres – which is a lot for those of us who reside at sea level! The trail takes you through diverse alpine terrain, including dense forests, open meadows filled with wildflowers, and rocky slopes as you approach the summit.

I was super excited about being in this great part of Southwest Colorado, however, my lungs weren’t feeling the same way and with every feature of the climb I would either pedal over it and run out of breath, or push over it and still run out of breath. Travis gave some words of advice – everything in slow motion, push the pedals then back off a touch at this higher altitude. This wisdom served me well and meant we could keep ascending the trail. The beauty was everywhere as we passed through forested areas and alpine meadows.

One of the most striking features of this ride is the geological formation of Engineer Mountain itself. The peak stands at 3,952 metres and is known for its unique shape — a flat-topped mountain with steep, dramatic cliffs on one side. This formation gives the mountain a distinct profile that’s visible from miles away. I was stoked I made it to this part of the ride, as it would be mostly descending from here onwards – and we could snack here and admire the view as we were above the tree line. From the top of Engineer Mountain, you are rewarded with panoramic views of the surrounding San Juan Mountains. It was a relatively clear day so we could see in every direction, taking in the rugged beauty of this part of the Colorado Rockies. The sweeping vistas from the summit made the effort all the worthwhile.

The descent was nothing short of bloody brilliant. Starting from high above the tree line the trail unfurls before you like a beautifully ribboned piece of singletrack, snaking its way down the mountainside. As you drop in, the upper section serves up some properly techy features with enough exposure for you not to peak too hard. It’s the kind of riding that demands your full attention — one wrong move and you’ll be telling the wrong kind of tales! Then comes the epic plunge into the forest. The transition is dramatic, from wide-open vistas to a green tunnel of trees. Pockets of Aspen pop up here and there, their leaves shimmering like nature’s own disco balls as you whiz past. The contrast is striking, adding another layer to the sensory overload.

The singletrack in the woods is super tight. It keeps you on your toes, or rather, on your game. The line of sight isn’t always there, so you’re riding as much on instinct as on sight. It’s a constant cycle of react, adjust, and send it. Every corner is a new surprise, every straight a chance to let it rip before the next challenge. And oh, the dirt! It was in absolutely prime condition — the recent rain had worked its magic. The grip made me push hard into every turn.

Even though the thin mountain air has you gasping like a fish out of water – altitude is no joke — I couldn’t wipe the grin off my face. It’s the kind of run that reminds you why you fell in love with mountain biking in the first place. The blend of challenge, speed and raw natural beauty creates an intoxicating cocktail of adrenaline and endorphins. As I finally rolled to a stop at the bottom, legs burning and lungs heaving, I was already scheming about how soon I could get back up there for another go. I plonked myself in the carpark whilst Travis pedalled his way back up to the van. Its fair to say this legend was a real host, showing off that good ol’ American hospitality.

We continued that theme with an after-ride stop at James Ranch for a burger, fries and soda. James Ranch is a family-owned and operated sustainable farm nestled in the beautiful Animas Valley, this 400-acre ranch has become a local icon for its commitment to regenerative agriculture and high- quality, farm-to-table food. The burger and fries tasted great as we sat amongst the picturesque setting reflecting on the day we’d just had.

As the thunderstorms rolled in, a rest day was on the cards — and after the past few days of relentless riding, it was welcomed. It also gave me a chance to check out the town, although I had been venturing out there every night for a meal — and often yarns with the friendly locals. Durango boasts a vibrant culture that blends Old West charm with a modern, outdoorsy spirit. This small mountain town is known for its diverse culinary scene, which punches well above its weight for a city of its size. Local restaurants showcase farm-to-table ethos, often sourcing ingredients from nearby farms and ranches. It has everything from upscale bistros serving innovative Rocky Mountain cuisine to laid-back brewpubs offering craft beers paired with gourmet pub grub. The town’s culinary landscape is influenced by its proximity to New Mexico, resulting in a notable Southwestern flair in many dishes. I particularly liked these dishes and it’s just not something we get a lot of in Aotearoa. Durango’s food culture is complemented by its thriving arts scene, numerous festivals, and a strong emphasis on outdoor recreation, creating a unique blend of mountain town authenticity and cosmopolitan sophistication.

Travis pinged me and said the forecast is looking good for an early morning high country ride. I was very excited to get back up there! Travis had cleared his work backlog the previous day and was pumped about this ride. This time around we’d ride a section of the Colorado Trail. This iconic long-distance hiking and mountain biking route stretching approximately 782 km from Denver to Durango. Winding through the heart of the Rocky Mountains, this epic trail traverses eight mountain ranges, six national forests, and six wilderness areas, offering breathtaking views of Colorado’s diverse landscapes. It ranges in elevation from 1,600 metres to 4,000 metres, challenging adventurers with high-altitude terrain and unpredictable mountain weather. The trail provides a quintessential Colorado experience, showcasing alpine meadows, pristine lakes, dense forests, and rugged peaks. The plan was to tackle some of the Durango end of the trail, so we took a longish drive up an access fire road to then descend (well, mostly) back into town. Again, we were back in the high country with thin air, but it wasn’t as high as Engineer Mountain and maybe I was starting to get acclimatised?!

With the van parked, bikes unloaded, jackets zipped up, bags packed and strapped on, we dropped in. The trail was lush, a touch overgrown and a bit damp — but splendid. The thin singletrack cut its way down the mountainside allowing for high-speed sections before zigzagging back on itself. The first part of the trail went by swiftly. Before we knew it, there was a river crossing and a climb on the other side of it. The gradient was relatively good in most spots so at least I could keep my gasping lungs under control. It did take a little while, but eventually we plateaued out with a nicely placed lookout. Lunch was in order — we’d grabbed a few extra supplies from the Mexican joint we hit up before heading out. I unpacked the tinfoil to Mexican heaven in the high mountains. A few riders pulled up and we exchanged yarns. The next part was fast, fun, rowdy and quite technical in places. The trail seemed to go on for ages and my hands and feet were starting to get tired. But, I couldn’t let the fatigue stop me! I was treated to sweeping vistas of the Animas River Valley, lush alpine meadows bursting with wildflowers and dense stands of aspen and conifer forests. The trail kept winding its way down from high-altitude terrain.

This was spectacular and we bombed further down the trail, glimpses of Durango town were seen below. We reached the trailhead rather swiftly after more than two hours of mainly descending. Travis was a trooper and again pedalled back up to fetch the van which was no small feat! I pedalled back into town and stopped for a cold brew en route to Lola’s House. I will be back to ride the full Colorado Trail at some point that’s for sure!

For the last few days, I hung out and rode some of the same in-town locations as earlier in the week. I was itching to get back to the high country, but the weather forecast didn’t allow for it. One last ride with Travis was around Animas Mountain, which is one local MTB park I hadn’t hit up yet. Animas High Bike Park is a relatively new addition to Durango’s impressive mountain biking scene. This purpose-built bike park offers a variety of features designed to challenge riders of different skill levels. The park includes flow trails with bermed turns and rollers, technical sections with rock gardens and drops, and a pump track for developing skills.

Each MTB Park in Durango is quite unique and this one had its own charm. I particularly liked Animas trail’s rock features which are predominantly composed of sandstone and shale, remnants of the area’s ancient seabed origins. These rocks create natural features, obstacles, and technical sections throughout the trail, which had me walking in parts whilst admiring the impeccable bike handling skills of Travis. As for the flora, Animas is characterised by a mix of pinon-juniper woodlands and ponderosa pines, interspersed with drought-resistant shrubs like sagebrush and cacti, and punctuated by colourful wildflowers in season, creating a diverse ecosystem typical of Colorado’s high desert and mountain transition zones. The vegetation is generally sparse, allowing for open sightlines on the trail — and the newly built flow trails are pretty damn fun. There’s a lot of elevation to gain and descend — as with most of Durango’s MTB parks — so ensure you pack good legs! This mix of rocky features and native plants creates a quintessential Colorado riding experience.

After more than a week in town, I finally headed to Durango Hot Springs. I looked over at the mountains as the sun was setting and was incredibly grateful that I ridden in a slither of those hills. I tried to stay present and let this moment soak in (literally). The hot springs were the perfect way to end an amazing week in Colorado’s southwest. The time spent here was made special with local legend and all-round good guy Travis Brown leading me around some of the best spots in his local hood. It really was something to hang with him, ride, eat and understand what makes up the character of this place. His in-depth knowledge of mountain biking and our shared passion for the sport made for long flowing conversations, reminding me that the bike is a great portal for human connection.

In essence, Durango offers a unique blend of historical charm, world-class trails, and a community that lives and breathes mountain biking. It’s a place where the legacy of mining has given way to a new kind of gold rush — one measured in singletrack miles and epic rides through some of Colorado’s most stunning high country.

SRAM all day

Words Ben Hildred

Images Callum Wood

Sun up to sun down; one final push; extend the loop; another lap; just keep going.

SRAM has created an event in Whistler to celebrate their new transmission, a way to push participants and blur the gap between type one and type two fun; T-type fun, maybe?

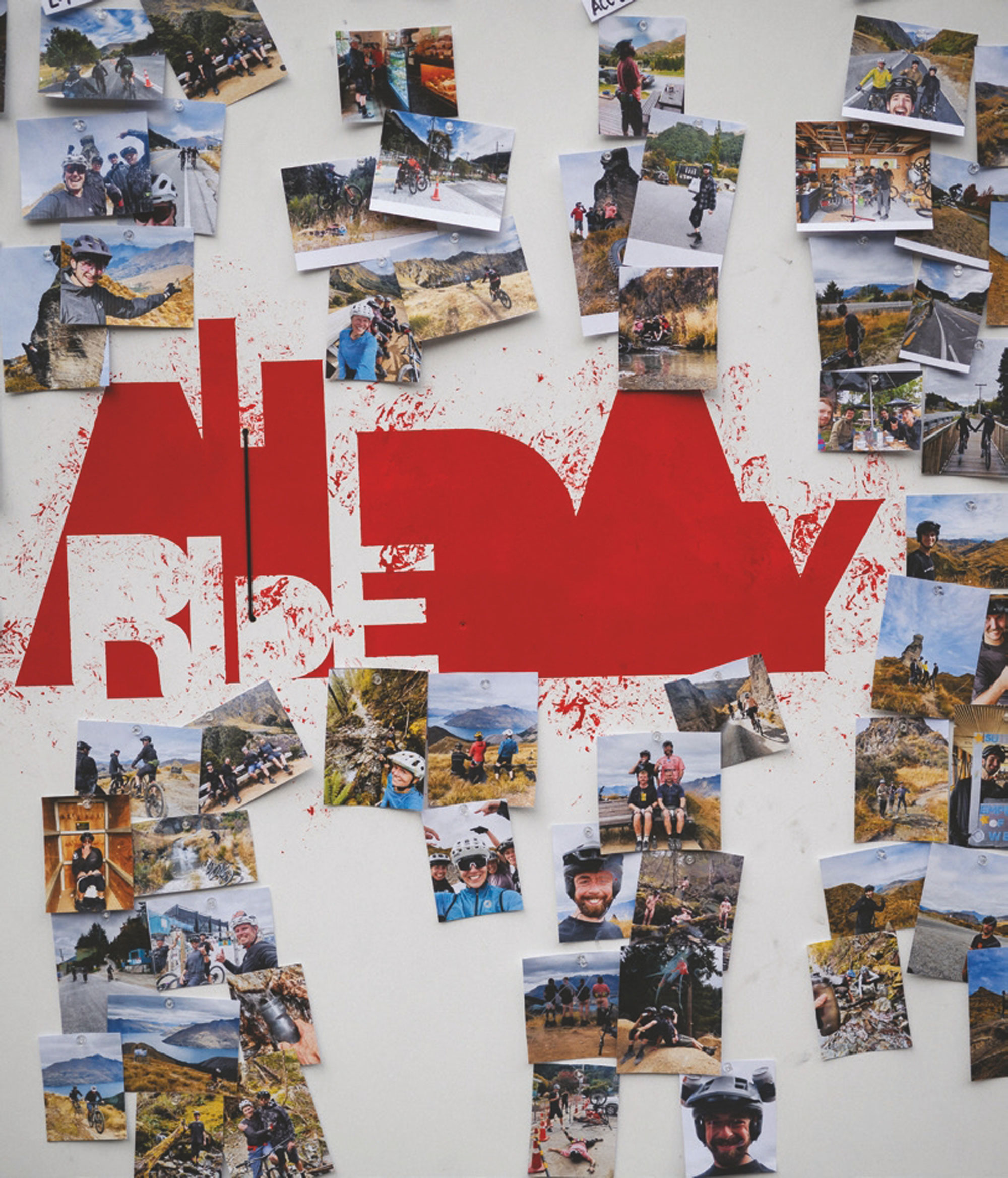

The original event was a great success during the Canadian Crankworx stop. Feedback and stories from its inaugural spin justified it as an event to be repeated – but why wait for summer to roll around again in B.C when Queenstown’s best season is in full swing? Let’s do an All Day ride here too!

I was tasked with the effortless mission of persuading 40 friends to enrol for a day of fun and riding bikes with a loosely formed plan. In a town of keen beans it was pretty simple, and with the promise of a beer and food provided by SRAM, at Atlas after their pedal, it was on.

Ten teams of four met at Atlas first thing to get briefed, receive an ‘All Day’ handbook and create their own adventure. Each team was given the same seven checkpoints; get to all the checkpoints, take a team photo, send it to me and return to Atlas. How you get to the check points, the trails you use and the routes you take was up to each team. Meanwhile, I’d be at Atlas ‘all day’ with a colour printer, documenting each team’s mission live, printing off the checkpoints, as well as other images the teams saw fit to send, and creating a story board for everyone to see on return. Easy as!

I was tasked with the effortless mission of persuading 40 friends to enrol for a day of fun and riding bikes with a loosely formed plan. In a town of keen beans it was pretty simple, and with the promise of a beer and food provided by SRAM, at Atlas after their pedal, it was on.

I spent the day on my toes, printing and pinning the snap shots of my friends’ ‘trails’ and tribulations. Recovering from a big ride the weekend before, I didn’t think I was in the mood to pedal, although seeing the laughs, predicaments, comradeship and pursuits everyone was on made me remarkably jealous, although stoked everyone was having a blast. The photos tell the stories. The teams were varied: a team of troopers headed by local force on a bike, Erin Greene, went hard on the adventure aspect, taking the most offbeat route over the mountains. Meanwhile, team Scotland, steered by Craig ‘Crug’ Munro shipped his motley crew around, surviving on their favourite fermented fizz – the one consistent every time my phone beamed updates were their smiles. The locations chosen meant teams had to visit Coronet Peak’s famous Rude Rock, grind up to the Ben Lomond saddle, dive down into Skippers Canyon, visit Wynyard’s famous jumps and sit atop McGazzas big table – all elements of an epic Queenstown adventure. Once all checkpoints were checked, teams started to return in the late afternoon, with stories to accompany the timeline of photos that awaited them, pinned up for all to see. Teams had averaged 2000 – 2600 vertical meters over 50 – 65km, mostly off-road. The question that concluded the day: when can we do that all again?! Logan Weber; “I had the best day pedalling I’ve ever had! For sure hope this happens next year!” The All Day ride was Logan’s biggest day on the pedals to date. After severely contracting the type two bug, he went on to complete an Everest a few weeks later! A huge thanks to SRAM for suggesting the event be held in Queenstown, and for funding the day; and to Atlas for hosting us all – the best bar around! What a time.

Checkpoints: McGazza Table; Ben Lomond Saddle; Beached as;Wynyard; Rude Rock; THE Rude Rock; Pack Track and Sack river crossing; Conestown.

Your time is now

A poem by Noell Coutts

Images by Callum Wood

Seek the rugged wilderness, the mountains and the sky

Feel it, breath it, watch a

Falcon Fly.

Hear the creek beds in the rivers, where miners searched for gold

Abandoned huts and buts of stuff, hear the

stories told.

The lust for gold,

the search, the thrill, the ghosts of days gone by The adrenaline, the buzz of it all, try and you’ll know why

Sometimes you go up, we all go down, sometimes the whole world’s

just spinning around

The

excitement

The

rush

The

thrill of it all

The

bumps and the bruises, the jumps and the falls

Time is the treasure, each hour of the day, but remember the clock only can go one way. Your time. Is now.

Coronet Loop Trail – Backcountry Escapism

Words Liam Friary

Images Jake Hood

“Queenstown already has enough trails!” – said no one, ever.

Enter the Coronet Loop Trail – a very welcome addition to the plethora of fantastic trails in and around Queenstown. The iconic southern town provides a home for many forms of riding culture; from gravity and jump to XC, tracks and cycleways, there is something available for everyone to enjoy, from the local shredder to the repeat visitor who heads there every chance they get. And, if you still haven’t experienced the riding in Queenstown, what are you waiting for?! Just be warned: this is the sort of place that will have you returning again and again, as you find more and more trails to ride with every visit.

As for the new Coronet Loop Trail – the Queenstown Trails Trust, in collaboration with Soho Properties, the QEII National Trust and Mahu Whenua – opened it in March 2022, after five years of hard graft and planning. The remoteness of this particular trail only emphasises just what a remarkable feat this collaboration – and the trail building itself – really is. The Queenstown Trails Trust is a charitable trust responsible not only for the planning and development of the Coronet Loop Trail, but more than 200km of trails in the Whakatipu Basin as well.

As far as backcountry mountain biking trails go – the Coronet Loop Trail has it all. The singletrack winds its way into the wild, through lush bush and across river gorges, deep in Queenstown’s remote backcountry. All of this, plus the rich history of mining in the area, ensures a non-stop sense of wonder as you make your way around the loop. The 50km trail has been well-crafted by technical trail builders and teams of volunteers, navigating its way around the mountains with gorgeous vistas that are forever changing. In terms of fitness, a moderate level is recommended due to the 1700m elevation gain across the entire loop.

The remoteness of this particular trail only emphasises just what a remarkable feat this collaboration – and the trail building itself – really is.

The History

The area was once a hot spot for gold miners, who arrived in the 1860s, seeking their fortune in the Shotover and Arrow Rivers. It was a bleak existence for those who had travelled from far and wide in an attempt to strike it rich, and although 340kg of gold was mined from the Arrow River in 1863, many were unsuccessful in their attempts to find their fortune. The remoteness of the area required some hairy travel techniques just to get to it, making it hard to believe it’s now possible to complete this loop in a single day of enjoyment aboard a modern bicycle.

The Ride

As mentioned, the Coronet Loop Trail is a 50km track, which is graded as an intermediate Grade 3, and takes roughly 4 – 8 hours to complete. It’s considered a more challenging experience than the rest of the Queenstown Trail Great Ride, so it’s worth bearing that in mind before setting out for the day. All that is to say, if it’s a backcountry adventure you’re after, this is the trail for you.

The trail can be ridden in either direction and is a two-way track that is shared with downhill riders and walkers alike. It’s worth noting that there is a more technically challenging section of trail as it climbs up and over into Skippers Canyon, on the Tradesman’s and Pack Track and Sack trails – to bypass this, you’ll need to take the Skippers Pack Track or follow Skippers Road before joining the climb up to Greengate Saddle. Remember this is remote backcountry, so we recommend pre-trail fuelling in Arrowtown before you head out, like we did, carrying plenty of food and hydration, and celebrating your achievement when you return later in the day.

Golden mountains, fresh creek crossings and a couple of spectacular waterfalls.

The Experience

We took our own advice and grabbed a caffeinated brew and a scone before we tackled the loop from the trailhead in Arrowtown. Mark (Willy) Williams, CEO of Queenstown Trails Trust, legendary local rider and mountain bike racer, would be guiding us for this ride and, after our second round of brews, we were ready. I pedalled for a few minutes and, before I knew it, we were buried in the beautiful Bush Creek. The trail follows the creek through native beech forest and, thanks to another recent upgrade, now has several sturdy bridges fording the numerous river crossings. The trail climbs up a series of switchbacks onto the southern face of Coronet Peak. We stopped for a short break to eat a snack, drink water, and take in the splendid scenery before continuing to follow the Coronet Face Water Race. This precarious trail, hugging the side of the mountain, was previously used in the gold rush era to transport water to the Arthur’s Point sluicings, some remnants of the past remain as a reminder of the area’s rich history.

We got around the southern side of Coronet Peak, with Lake Whakatipu glimmering in the distance. I was in awe of the view but didn’t have the breath to say much as we summitted the highest point of Skippers Saddle (949m). I have ventured into Skippers Canyon by bike numerous times and was excited to be back again on the recently renovated Pack Sack and Track trail. The long view down the aptly named Long Gully sees the trail twist and turn out of sight. It’s here that you transition into more backcountry riding and leave the confines of society behind. The trail helps you easily navigate this transition as it twists tightly down the expansive, dusty valley. I descended into the trail, where the rowdiness of riding a gravel bike quickly became evident. I was nearly bucked from my bike at the beginning but managed to stay upright somehow. We transitioned back onto flowy singletrack, which took us down the mountainside, offering endless picturesque views.

As far as backcountry mountain biking trails go – the Coronet Loop Trail has it all.