Trail Fund(s) tools for trails

Words Meagan Robertson

Images Lisa Ng

Talk about the gift that keeps giving! Thanks to Trail Fund’s recent Tools for Trails funding round, 30 Weapons of Mass Creation will help ten clubs continue their hard work creating and maintaining their local masterpieces. Read more on a few clubs and their plans below!

Since it was founded in 2013, Trail Fund NZ has been helping volunteer trail building groups around the country establish themselves and their trail networks by gifting grants, ebarrows and other tools. This Christmas, ten trail building teams up and down the country will have more tools in their sheds to further develop the amazing network of mountain bike trails around New Zealand.

“Tools are truly the gift that keep on giving, so we’re super stoked to support these clubs—large and small—with trail building and maintenance support,” says Trail Fund NZ co-president, John Humphrey. “It’s really about supporting the volunteers out there choosing to spend their time trail building – they are the ones behind the incredible trail network that has been developed in New Zealand, and that so many of us enjoy.”

The Swiss army knife of trail tools To make the application process simple, Trail Fund decided the tool of choice would be the New Zealand-made ‘Weapon of Mass Creation’—touted as the Swiss army knife of hand built trail tools, made by product designer and trail builder, Gareth Hargreaves.

“I’m a big supporter of Trail Fund and was more than happy to offer the tools at a discounted rate to get them into the hands of trail builders around the country,” says Gareth, who is a longtime member of the advisory board.

It turns out the clubs were pretty excited about the idea too, with Trail Fund receiving ten applications for the Weapon of Mass Creation (WMC) tools on offer from a wide variety of groups. Keen to see all the deserving recipients get some tools, Trail Fund decided to go big and grant each trail building group between two and four tools!

Read more about the recipients below….

Mākara Peak Supporters—Wellington

Established by Wellington City Council in 1998, Mākara Peak Mountain Bike Park boasts the largest trail network in the lower North Island and has had an exciting year celebrating the 25th anniversary of the park.

“The Mākara Peak Supporters are super stoked to receive three WMC tools from Trail Fund in their latest tool round,” says Mākara Peak Supporters member, Andrew Cooper. “It caps a great year for the Mākara Peak MTB Park—with 2024 being our 25th anniversary and being announced as the best park in the country for 2024 by Recreation Aotearoa – a fantastic acknowledgement of our collaboration with Wellington City Council.

“The WMC tools have been a mainstay of our trail building and maintenance mahi over many years and some of them are starting to feel their age. With a pipeline of refurbishments and new trail builds coming up at Mākara Peak, it will be fantastic to restock the armoury with these new tools.”

Bike Methven—Canterbury

Based in Methven, and only a 10-minute drive from Mt Hutt, Bike Methven has a mixture of cross-country, enduro and downhill mountain bikers, as well as road cyclists, who are passionate about their riding.

The club’s home base, Mt Hutt Bike Park has more than 40km of XC, downhill and singletrack trails and is looking forward to hosting the 2025 and 2026 South Island Secondary MTB Champs.

“All the tracks we are racing will need some love this season,” says club chair, Stu Marr. “We have a number of young pinners keen to get involved and get their hands dirty doing some of this work, so it’s awesome to be a recipient of four of these tools!”

In addition to prepping all the trails for the champs, Bike Methven’s latest projects are extending the intermediate level tracks around the lower part of the Bike Park and a UCI spec BMX track in Central Methven.

Mountainbike Tauranga—Tauranga

A first time Trail Fund recipient and the host of the 2025 North Island Secondary MTB Champs, Mountainbike Tauranga is thrilled to receive three Weapons of Mass Creation to help make its current major projects at Oropi Grove a reality.

A mountain biker’s playground, Oropi Grove is Tauranga’s longest serving mountain bike park. Located on Tauranga City Council land, it includes cross-country, downhill and freeride terrain featuring a variety of purpose-built jumps and drops and ranging from Grade 2 to Grade 6. The projects currently underway include a skills development park and a Grade 4 downhill track.

“The skills area will be a focal point of the park—an area where riders of all abilities can practice their skills, and organised mountain bike lessons can take place,” says Mountainbike Tauranga committee member, Shannon Fisken.

“The new Grade 4 downhill track is a requirement for hosting all three disciplines (XC, Enduro and DH) at the 2025 North Island Secondary MTB Champs. It’s already been professionally designed and our team of volunteers will assist our professional trail builder to ensure the project is completed in a timely and cost-effective way.

“These awesome new tools will be useful on a weekly basis for our committed Thursday night crew, and at our regular working bees prior to events. Thanks Trail fund!”

Other recipients include:

Richmond Hill Trail Carvers – Nelson region

Raglan Mountainbiking Cub – Waikato

Queenstown Mountain Bike Club – Otago

Mountain Bikers of Alexandra – Otago

Nelson Mountain Bike Club – Nelson region

Silvan Forest – Nelson region

Kerikeri Mountain Bike Club – Northland

Samara Sheppard: Ups and downs

Words Lester Perry

Images Phillip Sage

For over ten years, Samara Sheppard has been quietly going about her business, making moves and climbing the global off-road racing ranks.

From Wellington PNP races and NZ National Series events, to U23 XCO World Cups and Marathon World Championships, her career up until 2024 had been primarily based around mountain biking. The new year brought a change in focus and renewed motivation, prompted by a maiden voyage at the ABSA Cape Epic and a run at the US-based Lifetime Grand Prix series.

Born in Clyde, Central Otago, Samara’s family moved to Wellington in her fourth year. Raised in an active family, she was destined to become an athlete of some sort. “My dad was into adventure racing and endurance events like the Coast to Coast and Ironman. My brother also took to cycling but steered more towards downhill racing, as well as rugby. We mostly all ran cross- country. Mum would taxi us around. My sister, a brilliant swimmer and very intelligent—she often found smarter ways to spend her time.”

Not one to be pigeonholed into a single sport, Samara “played every sport under the sun and particularly enjoyed gymnastics from a young age, then onto netball, soccer and cross-country running”. In years to come, this excitement for running would ultimately open the door to mountain biking for her.

“I had a lot of energy as a kid and was able to channel this into gymnastics. But, as I was getting older and other sports like netball and soccer became available, gymnastics was becoming a full-time sport. I quit gymnastics to try out new things. I remember some Saturdays when I was around 12 years old; I would have soccer first thing, then a game of netball, then a running race, and then dance practice. Hardly surprising that I developed a taste for endurance sports!”

After being sidelined by a running injury, Samara’s father steered her toward mountain biking as a way to stay sane. “Once I discovered how awesome it was to adventure through Wellington’s hills and around NZ, I was hooked. I started racing straight away in the local PNP club events and loved the buzz.”

School life provided two critical things for Samara: socialisation—she wanted to hang out with her friends all day—and the schoolwork satisfied her competitive spirit.

“I always found maths easy, and I treated the work like a race, always trying to be the first to complete the work with accuracy. I think I still have the record at Churton Park School for quickest to complete the basic facts sheets.”

By high school, when she could choose her own subjects, MTB had started to rule her existence: “I chose to do the minimum subjects needed to pass NCEA so I could spend more time riding my bike.”

“My first seasons racing XCO in Europe as U23 were pretty exciting—getting to explore the world and racing against the best there is. The people you get to spend time with, new experiences, and the racing buzz is always rewarding. This year is exciting because it’s a whole new scene (to me) racing in the US, but it’s an easy one to navigate as it’s an English-speaking country and where the industry gets behind privateer riders. It’s really exciting to work with some of the best brands in the business and challenge myself in various off-road race formats.”

Although Samara continues to compete globally, the inspiration to keep pushing herself comes from those closest to her: “I’m inspired by my dad, the ‘old boys’ in Wellington, and the riders I’ve had the pleasure of competing against and riding with over the years. Today, my biggest influence comes from my husband, Kyle. He always keeps cycling fun and designs the best routes to ride. I’ve always raced well when I’m having fun. And Kyle has been a major influence for that over the past eight years.”

Many athletes appear one-dimensional, all- consumed by their pursuit of physical excellence, but Samara’s not one of them. Over the COVID lockdowns, with borders closed and racing paused, many cyclists took the opportunity to get a solid training block, emerging from the period fit and raring to go. Samara chose to further herself over the period and emerged with a master’s in public health. “I couldn’t leave our local government area, and there were no races. I was working part-time at a health clinic but was out of work with all the restrictions. I decided I needed a challenge and was motivated to get a reliable job through times like those. I was also aware of how lifestyles were becoming more sedentary and could see in the healthcare clinic the impacts that has. After the pandemic, I ended up taking on a role with Wollongong Tourism as a UCI Bike City Coordinator to help make cycling an easy option for people in the city.”

When US-based Argentinian racer Sofia Gómez Villafane was on the hunt for a 2024 teammate to try and reclaim the overall title she and Haley Batten (USA) won in 2022, Sofia’s 2023 teammate, Katerina Nash, suggested Samara could be a good fit. Both have similar backgrounds, transitioning from the short XCO discipline to the more endurance-focused marathon XC and gravel-style races. Sharing Specialized as a sponsor ticked the first box, and Samara’s palmares spoke for themselves: 6th at the 2023 MTB Marathon Worlds Champs, Oceania Marathon Champ, and NZ Champion, amongst other strong results; Sofia knew they were in for a strong performance. The southern hemisphere pair would take the start as an unknown quantity. Although this was to be Sofia’s fourth Cape Epic, it would be Samara’s first, and the pair hadn’t raced as partners before. South Africa wasn’t completely uncharted territory for Sheppard, however, as she’d raced the World Cup in Stellenbosch back in 2018. The pair ultimately finished 3rd at the Absa Cape Epic, Samara becoming the first Oceania rider to finish on the podium at this prestigious event.

Weeks later, the pair lined up for the Lifetime Grand Prix (LTGP) opening round at Sea Otter Classic, Monterey, California, racing head-to- head rather than as a team. Carrying strong form from the Cape Epic, Samara took the podium, finishing second, just behind Sofia—a solid start to the Life Time series. “I took confidence from Cape Epic and a deep strength in my legs which set me up for a perfect start to the LTGP. Backing this up with a result at Sea Otter helped secure more industry support that has made the rest of the LTGP possible.“

Taking on a series that not only covers a long time span but also criss-crosses the US, provides some unique challenges; her first LTGP series has thrown her some serious curveballs. “As a privateer, the initial challenge was securing enough support to do it. Then there’s the logistics of traveling around the US, which is just gigantic; navigating visas so we don’t overstay; and finding a home base in the US, as travelling back and forth wasn’t realistic. Races from April to October. Extremely long endurance events. High altitude prep.”

Fortunately, Samara was lucky to become part of the Orange Seal (OS) Academy, easing the financial strain and providing top-notch coaching support, working alongside ex-world- tour pro, Dennis van Winden. “Not only do they make excellent tyre sealant, OS also get behind riders and have created a community in the US with their OS Academy. If it weren’t for John, the owner of OS, and Dennis, the Academy lead, it wouldn’t have been possible to race the LTGP this year. I owe this season to their encouragement and support.”

The LTGP has been a significant learning experience. Unfortunately, some of the learnings have been to the detriment of her performance. The Leadville Trail 100 MTB race is renowned as one of the toughest races in the world. Over its 170km, the course covers a massive 3,600 metres of elevation gain, reaching a peak altitude of 3,800 metres—roughly the same as the peak of Aoraki Mt Cook. “Everyone responds differently to altitude. With two rounds of the LTGP being at high altitude, I made the call to come over to the US three weeks ahead of the first one to acclimatise. By the time Leadville came around, I had spent seven weeks at high altitude (around 2000m). It’s hard to feel good on the bike at altitudes above 3000m, so I would consider doing multiple smaller blocks next time around.”

“Coming into this season, I thought a 100km MTB race very long. Racing Leadville this year opened my mind to what it’s like to race all day. Well, for nearly eight hours, over the 170km MTB course. The longest race in the LTGP— Unbound—is 320km long. Unbound was my drop race this year because I couldn’t fathom how to race that far. After the race, I had a bit of FOMO, so I’ll be working on getting my head and body around racing for 320kms next season!

“Then there have been other challenges like a herniated disc in my back that flared up, getting bitten by a dog whilst out training, which sent me to hospital for ten stitches in my arm and a mighty dose of antibiotics, then recovering from a concussion after hitting my head on the ground racing SBT Gravel (non-LTGP race). The most challenging part remains—to achieve what I set out to do: I took on the LTGP because I believe I have what it takes to finish on the overall podium. The challenge remains to make it happen.”

Following SBT, the circus was off to Chequamegon, where she finished 10th and scored 7th place points (three non-LTGP riders in front of her). Samara was showing signs she was on the way back from her injuries and looking strong heading into the Marathon World Championship and the final two LTGP rounds.

Next up was to be the UCI World Championships in Snowshoe, West Virginia. Once again, luck wasn’t on her side. “It was my first ride on the Marathon Worlds course, and the course markings and .gpx files didn’t match up, so I was a bit lost. I’d found some friends to try to figure out the course with. It had been raining for a few days, so the trails were slippery. I was following one of my speedy friends down a technical section, and I didn’t see a small stump that I clipped my pedal on. I went over the bars and hit my knee hard on a rock slab, slicing it open, causing swelling and aggravating my bursa. It also triggered some concussion symptoms from a crash I’d had four weeks prior.”

“It was really sad to miss out on racing Worlds. I’ve loved the buzz of World Champs ever since I watched XC Worlds in Rotorua in 2006 and competed in my first World Champs in Scotland in 2007. It’s a special opportunity to represent your country and race the best in the world, chasing a rainbow jersey—a big goal of mine, especially after finishing 6th last year and 5th in 2019.”

Unfortunately, her injuries sidelined her for LTGP round six, The Rad Dirt Fest, so her focus shifted to the final round—Big Sugar in Bentonville, Arkansas. “This season has had its fair share of highs and lows. Dealing with so many injuries and setbacks in one season has been tough, especially since I took a break from work to compete in the U.S. The smaller setbacks, like being bitten by a dog and splitting my knee open, were relatively minor and straightforward. But the concussion has been a completely different challenge. Every concussion is unique, and people can only tell you to be patient and take your time. You just can’t push through symptoms like you can with other injuries. “I remind myself that there’s more in life I want to achieve, and for that, I need a healthy brain. I try to be kind to my body, not overthink things, and focus on what I can control—like getting enough sleep, eating well, and appreciating where I am. Having a strong support system with Orange Seal Academy, led by Dennis van Winden, who checks in every day and brings a wealth of data to guide decisions, has been a big help. Making a plan based on both data and intuition helps me stay positive and keep moving forward.”

Now in its third year, the LTGP has been refined and built on each successive season, but there’s still work to be done. “I don’t like how the women’s races are influenced by men who are racing on the course at the same time. It’s great that the pro women have their own start wave this year, but if the women could race on a clear course, that would make the racing safer and more fair.”

The LTGP is the largest offroad cycling series in the world, and even though the pointy end of the competition gets most of the media attention, all seven rounds of the series attracts thousands of everyday riders keen to toe the line against the pros. “It’s also super inviting for beginners to pro riders. Combining the LTGP with mass participant events creates a fun community buzz. The LTGP are doing great things to develop fandom, like with the incredible docos they release 48 hours after the race, the pro panel discussions, autograph signings and ways they promote their series.”

“Once the season is over, my focus will be on recovery and building toward 2025. I aim to come back even stronger and wiser. My goals are still big, with plans to return for LTGP in 2025 and tackle a mix of endurance and ultra-endurance gravel and mountain bike events. I’m excited for what’s ahead.”

Southern Legends: 100 years in one trip

Words & Images Jamie Nicoll

The St James area did not pull my strings until I bumped into Johno while on a bike launch assignment, checking out the new Hanmer Springs trails. My eyes were opened to yet another hidden world of magical riding and scenery to be treasured!

Johno is a pioneer of new trails and a visionary of our sport – in other words, he’s exactly the sort of person I try to find so I can tell their story. Johno works alongside Mark Ingles… yes, the legend himself. After losing his legs to frostbite in an alpine survival situation, Mark has gone on to inspire many generations through motivational talks and projects like this one; the development of the St James. This was to turn out to be a week of Kiwi legends! Johno and Mark are working together to breathe epic style into Hamner and the surrounding remote St James ranges. These ranges are steeped in history and the romance of a rugged life of working the land on horseback—and this is not just history but a present-day reality: I met a horseman out earning a crust through trapping and track maintenance.

This is a place where you can ride for miles and stay in huts; it’s basically an Old Ghost Road or Paparoa trail, except that it has always been there and therefore hasn’t received the marketing attention. All you need to do is look at a map, follow the dotted lines between huts and you are done; you have created your own hut-to-hut adventure on good trails and singletrack with epic views. This area sports a lot of good weather days too, which is worth noting in case you were planning to ride into the mist and rain elsewhere.

Now, I live in Motueka, and I like going places via routes less trodden, so I turned the key on the tried and tested, global-expedition-equipped Land Cruiser with a bike strapped to the back, and headed for the rough roads. From Blenheim, one can access a gravel road heading south 120 km through the Molesworth Station, NZ’s largest station, and the road to Hanmer Springs. The Molesworth road is gravel and remote but can be driven in any sensible car, and allows you to drop into the back of the Hanmer Springs township.

After two days of touring, we pulled the trucks up at Johno’s house for an evening of poring over maps. The next morning the plan unfolded, with Mark Ingles shuttling us out to the start of Fowlers Pass on the Rainbow Road while my trail building mate, Sam, and his brother, drove the two Land Cruisers into a side valley to set up a welcome camp at Scotties Flat hut.

Fowlers Pass has a lot going for it. It sits at 1296m altitude with a smooth singletrack climb and loads of promising and stunning terrain. This was the start of chasing Johno on his eBike for the day. With a good portion of the climb done, we rounded a corner and there was some real-life Kiwi-as-you-get, grey-bearded, Swandri-wearing, horse-packing dude cruising along beside his mount. His name was Sean. His horse has no name but carried the most basic of set ups, using sacks as saddlebags—I thought I’d hit my head and gone back in time! Sean spends 11 months of the year in the backcountry, trapping possums for fur and repairing trails so horses – and subsequently, bikes – can pass through unhindered. Sean is actively involved with a group that focuses on establishing and re-opening historic horse trails throughout the South Island. Man, did this guy blow my mind… legend!

Descending off the pass, tight schist-y singletrack turned and a smooth, narrow thread of trails snaked down the open landscape. This had me back in France, and the trails of the infamous Trans Provence race.

From a plateau meadowland, we peered down at Lake Guyon. Johno pointed out and explained more about the future trail development and links that will expand an already stellar array of backcountry and multi-day options. Think of it as a choose-your-own-adventure location. From the plateau, it was not far to the historic Stanley Vale Hut, dating back to the 1860s with remnants of wall paper and Mother Mary still hanging on the wall. I’d been told a story about some cyclists who had been snowed in at the hut, with Sean keeping them well entertained with stories over the bleak days!

The Stanley River, running south from this mountain grassland, boasts yet more singletrack. We generally maintained a nicely efficient pace, until we eventually climbed up out of the Stanley to ‘The Race Course’, something of a wide clay flat area. Again, you are privy to some of the most impressive views out west, up the Jones River and south down the Waiau.

Some 35km and six hours later we descended to Scotties Hut, down a newly cleared singletrack to a sweet welcome party of Sam and his adventurous kids. These are impressive kids—back home in Motueka the two of them spend days out playing in the forest while Sam is digging new MTB trails for a crust.

That evening, we headed to a remote “wild” hot pool not far from Scotties Hut. Wedged into a small side valley and beautifully located on the stream edge, the starry night above created a fine finish to a big day in the saddle.

Johno had only used 45% of his battery running on Eco for the day, but my legs were definitely spent. This was day four; bikes strapped to the Land Cruiser and headed out, we turned north towards Lake Tennyson and, more precisely, the rough road up to Mailing Pass. Standing at the 1308m pass we looked once more down to the beautiful grassland of the Waiau River flats. Johno pointed out the large pockets of beech forest nestled into the western folds and enthusiastically shared his trail vision for this descent, something worthy of a trip in its own right, once it is built.

With special permission from DOC, we were able to make a quick trip to look at Lake Guyon from the opposite angle. Standing at the Lake Guyon hut, we looked over this alpine lake up to the plateau edge I had looked down from only the day before. This gave me a good picture and understanding for the singletrack trail vision that would link these two tracks with not just old 4WD trails but outstanding singletrack terrain, making even more options for MTB backcountry adventures here!

Tired but stoked, we took shelter in the Island Gully hut in the middle of the scree-clad mountains of the Rainbow Road. Another night in the hills rounded out an epic adventure, rather than the all too familiar story of getting tired and over-focused on getting out. A fresh and happy bunch rolled back into the Motueka Valley with new and exciting trails under our belts and an eagerness to return for more!

Northern Lines

Words & Images Liam Friary

The Pacific Northwest has always held a certain mystique for mountain bikers. Its loamy trails, dense forests and mountainous terrain have been home to some of the world’s best shredders, and have helped shape the culture of our sport.

I was fortunate enough to take a winter hiatus earlier this year, to trip around some of North America. This part of the journey took me from the iconic trails of Bellingham, Washington, through British Columbia’s interior, ultimately landing us in Golden. The ‘us’ is me and one other – Chris Mandell. Just one video call led me to this situation; Chris was meeting a larger crew (travelling from other regions) in Golden for the 25th Anniversary of Psychosis, so I hitched a ride.

Bellingham served as our launch point; its reputation as a mountain bike haven is well- earned. The town sits nestled between the Salish Sea and the North Cascades, where trails seem to sprout from every fold in the landscape.

There’s a ton of riding options here and even if you spent weeks, you’d only just be scratching the surface. One of the main local riding locations is Galbraith Mountain. The network offers more than 65 miles of pristine singletrack that’s been methodically crafted over decades. Before heading north, we squeezed in an afternoon session on some of Galbraith’s finest. It was dry but the dirt was tacky, and the trails were so damn fun. Pacific Northwest trail builders craft with precision—berms and jump lines are dialled, but there’s also a heap of tight hand-cut singletrack. I was itching to get more trail time in, but we needed to gap it.

The van was packed. Two trail bikes, a DH bike, spare wheels, tyres, a heap of bike paraphernalia, clothes, some food and coffee and, after a quick homecooked lunch, we were set: ready to hit the road north. The border crossing at Sumas was relatively quick, and, soon enough, we were cruising through British Columbia’s Fraser Valley. The landscape gradually transformed from coastal rainforest to the drier interior as we pushed eastward. I was just trying to take everything in whilst also attempting to find an afternoon ride and dinner location. I wasn’t just a passenger, more like a co-pilot. We found a riding location to spin our legs, but it wasn’t really the mountain biking we were after as it was actually a cross-country ski course (in the winter, of course). We pedalled anyway as it was good to get the body moving again after spending a few hours in the van. We jumped back in and, within about ten minutes or so, we saw a heap of cars parked up at a trail head. Turns out that was a better location and had ‘real’ mountain bike trails. Oh well, that’s the joy of travel—right?!

After dinner in Kamloops, we pinned our first overnight stop to Salmon Arm. It’s a modest town on the shores of Shuswap Lake that’s quietly been developing its own mountain bike identity. The South Canoe trail network here is a testament to grassroots community building—local riders have turned hillsides into playgrounds, with trails that range from flowy cross-country to technical descent lines.

The morning light in Salmon Arm painted the lake in silvers and blues as we loaded up on coffee and breakfast sandwiches from a local cafe. After an hour or so of clearing the digital backlog, we were set for another day of road tripping. The air was crisp, typical of early summer in the BC interior. We surveyed Trail Forks and spotted a good trail en route. We drove the van up a fire road and parked at the trail exit. The climb up was peaceful, switch-backing through stands of cedar and fir with occasional glimpses of the Shuswap peeking through the trees. The descent was fast, flowing tight singletrack punctuated by natural rock rolls and root gaps that seemed purposefully placed by nature itself. I clipped a tree towards the end of the trail and catapulted myself off the bike. After a dust off, I fixed my bars and gathered myself before descending the rest of the trail. Stoke levels were high back at the van.

Golden was calling. But first: a short stopover in Revelstoke for lunch and multiple coffees. The urge to ride this iconic mountain biking location was at an all time high, but the timeline just didn’t allow for it, unfortunately. Here’s hoping I’ll get back there one day. Instead, we took in the historic charm of the town before hitting the road again. The drive east took us through some of BC’s most dramatic terrain—Rogers Pass cuts through the heart of the Selkirk Mountains, where glaciers still cling to peaks and the Trans- Canada Highway fits perfectly into the splendid scenery. The chat at this point was mostly about ski lines you could hit during the winter months. That’s certainly a trip for another time!

Golden appeared below us as we descended from Rogers Pass, nestled in the confluence of the Columbia and Kicking Horse Rivers, with Mt. 7 looming above like a staunch sentinel. The energy in town was all about the return of Psychosis. This is a race that had achieved almost mythical status in the mountain bike world, running from 1999 to 2008. After some dormant times, the race had been resurrected for its 25th Anniversary, drawing riders from here, there and almost everywhere to test themselves on one of the most demanding downhill tracks ever raced. Mt. 7’s course drops 1,200 vertical metres over seven kilometres, with some super steep gradients that would make a theme park seem lame.

The atmosphere in Golden was electric. The small town was buzzing, with bikes appearing from every corner. Our homestay for the event was an iconic local legend, Mark (Rabbit) Ewan. Rabbit had energy to burn and would not only house us but host us and get us anywhere we needed to be in Golden. It felt like we were with the mayor, as wherever we went with him in this small mountain town, he knew someone. His enthusiasm was infectious. Rabbit’s house was soon taken over by a flock of mountain bikers dossing down wherever space allowed. Thankfully, his wife and kids were out of town. A quick evening shuttle run was the order – I picked up the role of driver and the hoots and hollers on the way up were only louder on pick up at the bottom of the run. Rabbit took in some elements of the racecourse but wanted to venture off piste too. Dinner was served in the backyard, with bikes being tinkered with late into the night, thanks to the endless daylight that stuck around until 11pm.

Dawn was met with pancakes and maple syrup, washed down with coffee. Before long, we were driving back up Mt. 7’s access road, a rutted forest service path that twisted its way up. The view from the top is incredible and not only does it serve as a starting point for the riding trails, but a paragliding launch site, too. Columbia Valley stretched out below, with the morning mist still clinging to the river’s curves. Several runs later, the crew become a little more confident but there was still a nervous energy amongst them.

The race itself was a spectacle of human determination. Watching riders tackle the infamous ‘Dead Dog’—a steep, exposed section that had everyone’s hearts in their throats—was both terrifying and mesmerising. The level of commitment required to race this mountain at speed is hard to fathom, even for experienced riders. Between practice runs and race heats, the stories flowed. Tales of legendary runs from the day—and from the original Psychosis days—of broken bikes and broken bones, but mostly of the strong mountain biking community. Our crew all did well and kept their bikes upright and bones intact. The finish area party was strong, with music, beers, food and an electric atmosphere. This was all grass roots, with nothing flamboyant about it; as authentic as it gets. The crew were stoked to re-live yesteryear, reminiscing about the racing scene and how it reminded them that bikes have the power to bring like-minded people together.

Our final evening in Golden was spent at the after party, held at a local bar where racers, support crew and spectators celebrated hard with a 90’s punk band doing covers. It got quite loose as the intensity of the music ramped up – think: mosh pits, no shirts and an electric atmosphere that would rival some concerts these days. The return of this iconic event represents mountain biking’s raw soul. The stories shared that night weren’t just about racing, but the lifestyle that surrounds the sport, too. Psychosis is all about preserving a piece of mountain bike history and culture that often gets overlooked in the new era.

As we loaded up for the journey to my next location, Golden’s morning light painting Mt. 7 in alpenglow—it was clear why events like Psychosis matter. In an age where mountain biking continues to evolve and modernise, there’s something special about places that maintain their raw, untamed character. From Bellingham’s pristine trails to Golden’s rugged mountains, our road trip had traced a line through the sport’s past, present and future. The shared experience has become a core memory, at the heart of which is the strong and vibrant community that keeps the sport intact.

The Longest, Longest Day

Words Tom Bradshaw

Images Peter Wojnar

The idea was simple: fly to the Yukon, arriving at 11:59pm on Friday night. Greeted by the midnight sun of the summer solstice, we’d leave the bike bags somewhere and start riding. We’d ride the stunning Whitehorse trails until the 5pm flight on Sunday night, returning to Vancouver in time for work on Monday. No accommodation, no vehicles—just a big ride with plenty of stops and the occasional nap under the midnight sun.

It was ambitious to say the least.

Landing at Whitehorse airport ahead of schedule at 11:30pm on the Friday, we feverishly built up our bikes outside the terminal, in a twilight haze of disbelief and—to be honest—tiredness.

The Yukon is known for its remoteness; the gold rush, the Arctic Circle, and beautiful, expansive terrain.

It’s five times the size of New Zealand and, more than once, we would find ourselves “Yukon’d.” If you were to look up Yukon’d in the dictionary, it would be a verb describing the moment of realisation that, three hours into a climb towards a mountain top, it appears no closer than when you started.

The Yukon is less well known for its mountain biking, however, it is outstanding. The soil is a blend of water-sapping loam and near-sandy alpine dirt. The tree line stops at 900m of elevation, providing “easy” access to the alpine. The vastness cannot be underestimated.

Immediately, our plan was derailed. Unable to simply leave our bags in the bush by the airport as we had planned, we dragged them with us to the local bike shop. I-cycle, arguably the best named bike shop in the world, fortunately has a perfect covered patio where we left the bags. We began pedalling, into the darkness—and the rain.

As it transpires, even during the actual summer solstice the sun technically sets for about one hour. At this point it was 1:30am on the summer solstice and, because of the rain, clouds and technical twilight, our mood matched the unexpected darkness of the forest around us. There was no traffic and as we left the city limits, we realised how dark, wet and dumb this idea actually was.

Three hours later, at 4:30am, we finally broke the tree line. The 1000m climb had taken it’s time, as we paced ourselves and got lost a handful of times up the ever-expanding forestry road network. The visions I’d had of a four-hour-long twilight, painting the alpine and expansive Yukon landscape shades of a Picasso art piece, couldn’t have been more than a fever dream at this point. It was lightish, however, a grey misty cloud had settled, enveloping not only the sunrise but the view of Whitehorse entirely. At least we only had another 20 hours to go, a chance for the weather to clear.

As soon as we started heading downhill, the first bonk of the day disappeared. The low angle 800-metre descent was delicious, albeit spicy with the wet slick roots ready to catch a front wheel. The dirt was perfect, though, and held the moisture well.

The final 150 vertical metres was such a treat that we pushed back up and did it again. By the time we got to the bottom, it was 7:30am, and thoughts of hot, fresh coffee were pulling myself and Jacob to town. Fortunately Peter, who was also lugging around a camera, wisely told us we were being cowards and our short-sighted goal of hot coffee would add another 25km of road to our ride.

The mountains and their bike trails completely encircle Whitehorse. We had headed out to the west, and our next trail lay northwest of town. If Jacob and I were left to listen to our caffeine addiction, we would drop 400m elevation and have to ride back up the same road; it was a dumb idea inside a dumb idea. Instead, we listened to our bodies, and all promptly fell asleep. It’s amazing what 24 hours awake can do. We found a shelter, and passed out on the gravel like it was a California King. Some 20 minutes later, refreshed, we started climbing again—this time aiming for our second 1000m climb for the day: Whitehorse’s downhill track. The climb flew by; the proper daylight, improving weather and incoming fresh singletrack had us moving.

Haeckel Hill DH did not disappoint. Dropping in at about 10am we were treated to a handful of steep chutes with beautifully placed catch berms. The trail then went to that outstanding Rotorua- esque low angle, off the brakes gradient. We were riding like we hadn’t been moving for nearly 12 hours with 2000m of climbing under our belt.

After the 700m descent of beauty we had earnt a coffee. And a beer. This turned out to be a near-fatal mistake. Rolling back into downtown Whitehorse sometime after noon, we had been moving for about 12 hours and were all completely soaked. The bottoms of our feet resembled the contours on a topo map. They did not look pretty, nor did we. We were accepted to the local pub and found a table amongst the locals enjoying a rainy Saturday lunch. Fortunately, the people of Whitehorse could not have been more welcoming. They all seemed unperturbed by our soaking wet carcasses, and we celebrated the halfway mark by toasting to being inside and warm. The consequences of that lunch beer were almost immediate. It was all we could do not fall asleep in the warm, dry pub. Knowing we couldn’t afford to totally piss off the locals, we settled up and promptly fell asleep on the park bench across the road.

This was not the alpine wildflower bed sunshine nap I had envisioned when scheming this mission. But at this point, none of us could care less. Awaking to rain falling on us again, and seeing that it was 2:30pm, we decided we should really get going to climb up Grey Mountain, a 1400m mountain to the east of town.

Over the next three hours, we learned the hard way about the term “Yukon’d”. By 5:30pm it felt like we hadn’t even made a dent on the climb, however, it was starting to make a dent on us. We needed to stop to air our now trench foot-like feet every hour or two—the downside of our plan to only wear our riding gear on the plane. This travel light strategy was really starting to backfire on us as I considered pedalling barefoot for a spell. The fire road was pleasant enough, with a gentle gradient, and the three of us kept each other cheery while reminding each other of previous indiscretions over the past 18 hours. The animals of Whitehorse were clearly taking shelter, wiser than us; our only sighting was a small black bear, jumping out a few hundred metres up the road, glancing at us then deciding he had better things to eat than three smelly, tired, wet humans.

Fortunately, the higher we climbed, the clearer the skies got. The cloud broke as we reached the summit of Grey Mountain. It was 7:30pm when we were gifted our first proper view of the Yukon. The mountain had taken five or so hours to climb from town, but paled in comparison to what lay beyond. Mountains, lakes and the mighty Yukon river stretched as far as the eye could see. It was beautiful. And so was the descent.

Money Shot was the most technically challenging trail yet; steep, rocky and exposed as it descended through the alpine. Again, the descent gave us all a shot of life. All three of us rode like we’d just jumped off a chairlift, passing each other on inside lines and cackling at the trail. This was our first of two descents off Grey Mountain. We’d lost 600 metres on this descent and started climbing to the top for a second time, knowing midnight was getting close.

We knew we had to be at the summit by around 11:30pm. The light was fading and rain clouds were forecast to roll back in. We had ambitiously decided not to pack any riding lights, believing that “of course we won’t need them; it’ll be light the whole time”.

Regardless, we pushed on knowing this would be the final descent of our longest, longest day. We started climbing the final alpine ridge at 10:30pm. The cloudy, murky twilight wasn’t the hours-long beautiful golden hour sunset I had envisioned, but it was still breathtaking. The climb was also breathtaking. By this point, we had climbed well over 3,500m and ridden over 120kms on about 50ish minutes of sleep. The bonk was hitting us all hard.

It was only fitting that this final 1000m plus descent was called “The Dream.” A beauty; blue flow trail, hand-built by volunteers from the local mountain bike club, descended through the alpine back to the Yukon River and into town.

Naturally, we didn’t make the summit quite in time. As we dropped in at 11:45pm, the fading light and cloud made ‘The Dream’ a true and proper dream. Hooting and hollering like the delirious children we were, we scared any wildlife out of the way, the descent once again bringing us all to life. Twenty-four hours in, we were riding like it was lap one; the sandy alpine dirt providing unlimited grip despite the rain. The lights from town steadily got brighter as we got closer, and our grins were ear to ear.

As we rolled back to town at 1am, some 11 hours after we had left from our lunch nap, we realised how hungry and tired we were.

It’s fair to say we had drastically underestimated the logistics. I had planned this trip thinking we’d be riding through the hot summer sunlight, taking rests in fields of alpine wildflowers, and riding all the way through to our flight back on Sunday afternoon. Due to this overly ambitious plan, we had failed to book or bring any accommodation with us. We hadn’t really thought about that until this point, however, food was our number one priority. Whether you are in Whitehorse, Wellington or Warsaw, the golden arches of McDonald’s will always provide. The crispy, salty fries and magic Big Mac sauce filled a void we didn’t know we had.

Considering our options, sitting outside, soaked and bonked, we decided going back to our bike bags under the sheltered porch of the bike shop was our best move. And by god it was. To be honest, we probably could’ve booked a hotel, but we weren’t ready to drag our soaking wet carcasses back to society just yet.

Cozying up in a bike bag might not seem like the comfiest bed to you, if you’re reading this from the couch or the coffee shop, but at 1:30am in the twilight of a rainy Whitehorse morning, it couldn’t have been better.

A successful end to the longest, longest day ride. As the sun properly rose on Sunday morning, we sought shelter in the local coffee shop, promptly falling asleep again, but caffeinated, dry and relatively warm.

We spent Sunday testing out the local BMX track and jumps close to town, then rode back up to the airport, but only after a crucial stop to buy clothes for the flight home. Our strategy of packing only our riding gear had worked out so far, however, by now we were a biohazard. We would not have been allowed to board a commercial flight in the state we were in, so Walmart provided a pair of jandals and enough clothes to let us board the flight home.

Sitting down on the flight back to Vancouver, I felt relieved that the Yukon had let us get away with this atrocious lack of planning. The vastness was real, and a place I cannot wait to revisit with the bike—and perhaps a vehicle and accommodation. Nonetheless, we left feeling successful. We did it, but it wasn’t pretty. We had spent the entire midnight to midnight exploring the outstanding trails, people and town Whitehorse has to offer.

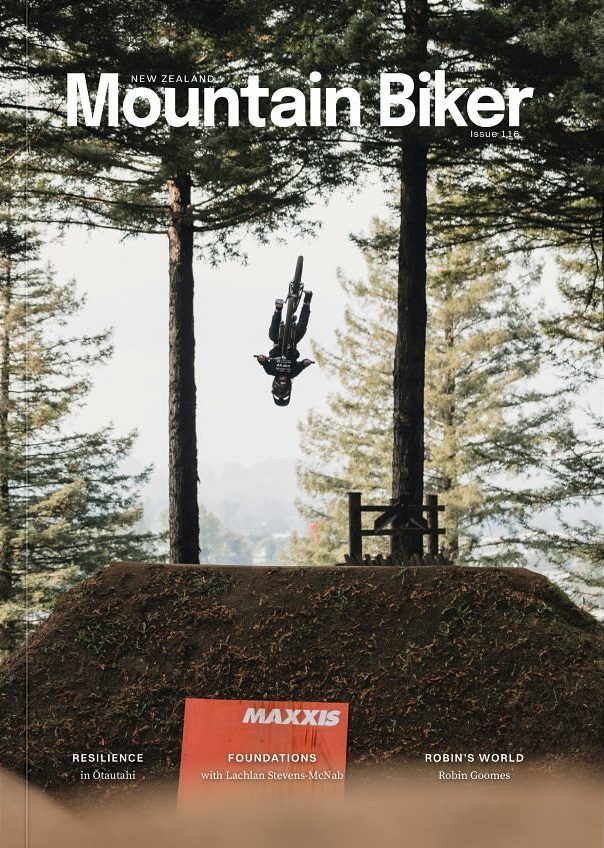

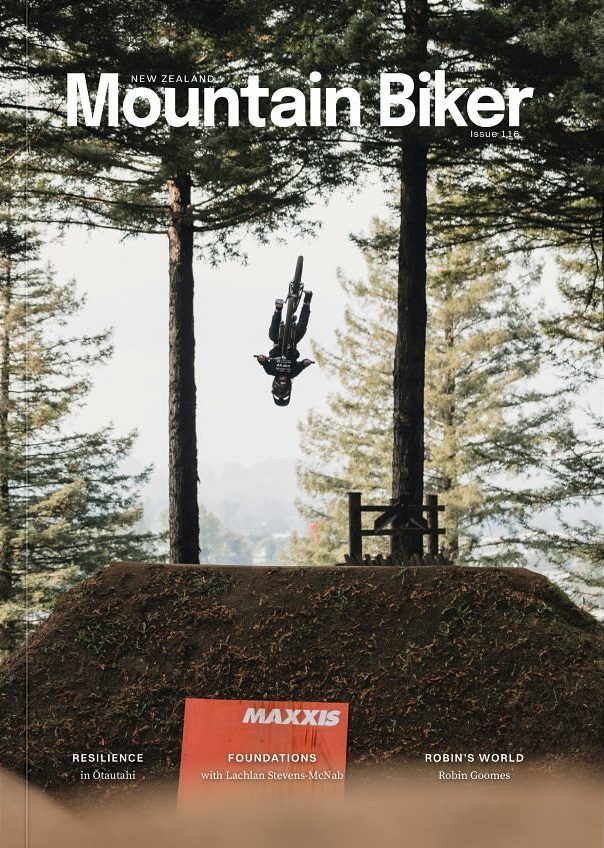

Resilience in Ōtautahi: Christchurch’s Mountain Biking Legacy

Words Lester Perry

Images Cameron Mackenzie

In the shadow of the Southern Alps, where tectonic forces have shaped both landscape and spirit, Ōtautahi Christchurch’s mountain biking community has written its own story of resilience.

In the shadow of the Southern Alps, where tectonic forces have shaped both landscape and spirit, Ōtautahi Christchurch’s mountain biking community has written its own story of resilience.

Like the native tussock grass that bends but never breaks in Canterbury’s fierce nor ‘westers, the city’s riders have proven time and again that adversity only strengthens their resolve.

The devastation of yesteryear has hardened city dwellers who have incredible forward momentum. These individuals are armed with spades and determination and, over the past decade or more, they’ve built new lines to prove their mettle on. Not only new lines appeared but new riding communities too and, nowadays, rider’s flock to Christchurch and its stunning surrounds to get a piece of the action.

The Port Hills, those ancient volcanic remnants that stand sentinel over the city, have always been more than just terrain. They’re the beating heart of Christchurch’s mountain biking culture. From the technical challenges of Flying Nun to the flowing contours of Anaconda, each trail tells a story. Simply ask around and you’ll hear rider’s tales of dawn missions before work, lights twinkling on helmets as they chase the sun up Mt. Vernon; and weekend missions.

When the Christchurch Adventure Park (CAP) emerged from the drawing board in 2016, it wasn’t just another bike park—it was a statement of intent. Heck, there was a ton of excitement in the air at the time and rightfully so. This would be the Southern Hemisphere’s first year-round chairlift-assisted bike park. It represented everything the community stood for: ambition, innovation, and that characteristic Cantabrian courage to dream big. The 358.5 hectare park became a testament to what’s possible when passion meets perseverance.

The 2017 Port Hills fires, that swept through CAP, could have been the end of the story. Instead, it became just another chapter in Christchurch’s tale of renewal. As the smoke cleared, revealing a changed landscape of blackened pine skeletons and scorched earth, the mountain biking community rallied. Volunteer trail builders worked alongside professional teams, adapting their designs to the new terrain. Where once there were forest lines, they created raw, exposed tracks that showcased the hills’ natural beauty. The park didn’t just survive—it evolved.

Today, Christchurch’s riding scene reflects this history of adaptation and growth. The city’s unique geography offers something for every rider. Beginners find their wheels at McLeans Island, where purpose-built tracks wind through river terraces. Urban warriors connect the dots between the city’s green spaces via an extensive cycle network that makes every ride an adventure. Intermediate to advanced riders push their limits at CAP, where world-class trails like Shredzilla and B-Line challenge even the most skilled athletes.

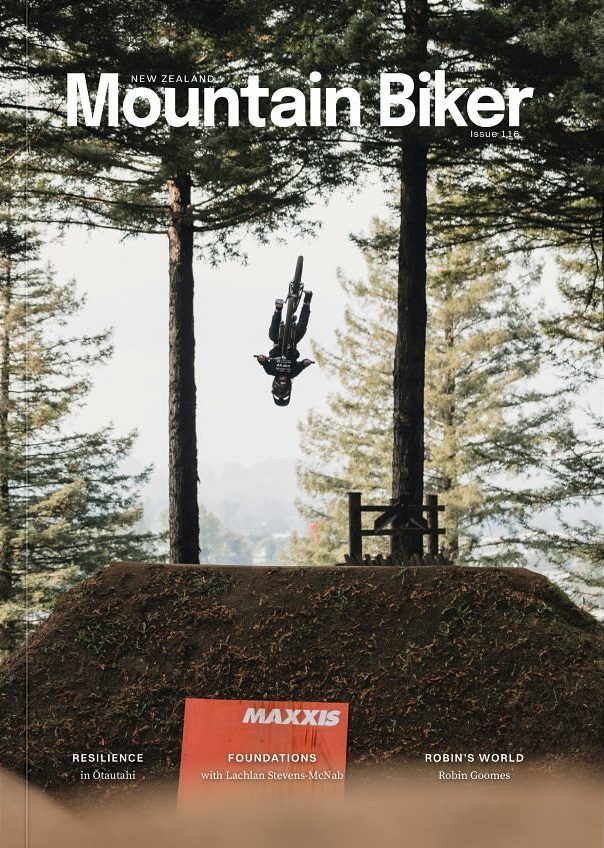

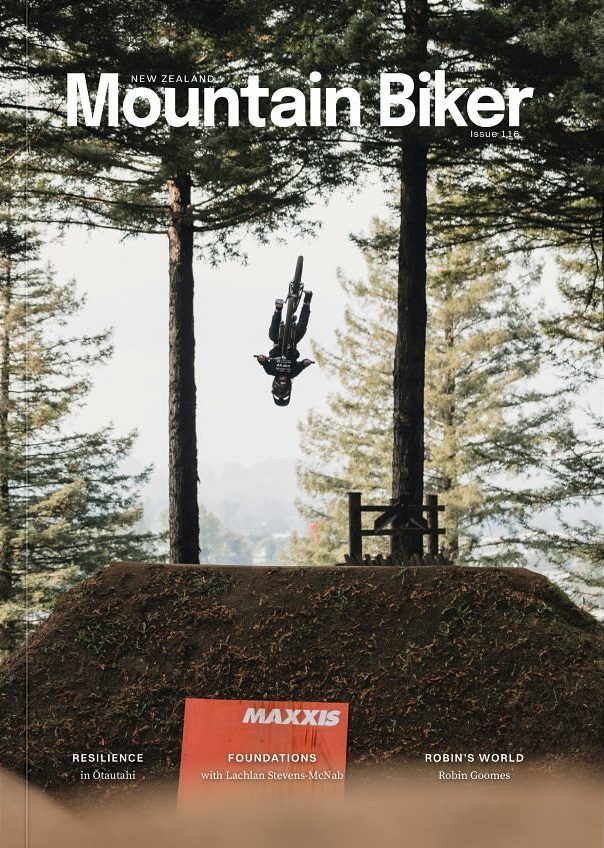

The highly anticipated Crankworx Summer Series is set to return to New Zealand in 2025, after the cancellation of the 2024 event due to the devastating fires in the Port Hills. The series will take place from 13th to 16th February 2025, with a new line up of events that will elevate the mountain biking experience for both riders and spectators alike, and will form part of the build-up to the first mega-festival of the Crankworx World Tour, in Rotorua from 5th – 9th March 2025.

The Ōtautahi Christchurch festival will introduce a new Freeride Mountain Bike Association (FMBA) Gold Level Slopestyle event, the first of its kind in New Zealand. The new course and competition is set to attract some of the world’s top Slopestyle riders and provide a pathway for emerging New Zealand talent. Alongside Slopestyle, the series will also feature Pump Track and Downhill, ensuring a weekend packed with action for spectators and athletes alike.

Beyond the established trails, Christchurch’s riding culture continues to evolve. Secret lines appear in forgotten corners of the Port Hills, carved by passionate locals who see possibility in every contour. Over the weekend, vehicles with bikes hanging off them head out of town with riders making the short trek to Craigieburn and Mt. Hutt, extending the community’s reach into the high country. Each new trail, whether sanctioned or social, adds another thread to the rich tapestry of Christchurch’s mountain biking story.

The city’s mountain biking infrastructure has become a model for urban planning worldwide. The Major Cycleway network, born from post-earthquake reconstruction, has transformed how people move through the city. Riders can now pedal from the International Airport to the Adventure Park without leaving dedicated cycling infrastructure – a journey that captures the essence of Christchurch’s commitment to two-wheeled adventure. What’s even better, is that you can store your bike box at the airport—perfect for a weekend riding getaway with no need for a car!

As the sun sets behind the Port Hills, casting long shadows across tracks both old and new, Ōtautahi Christchurch’s mountain biking community continues to prove that it’s not the challenges that define us, but how we respond to them. In the end, it’s not just about the trails – it’s about the people who build them, ride them, and keep coming back, no matter what nature throws their way.

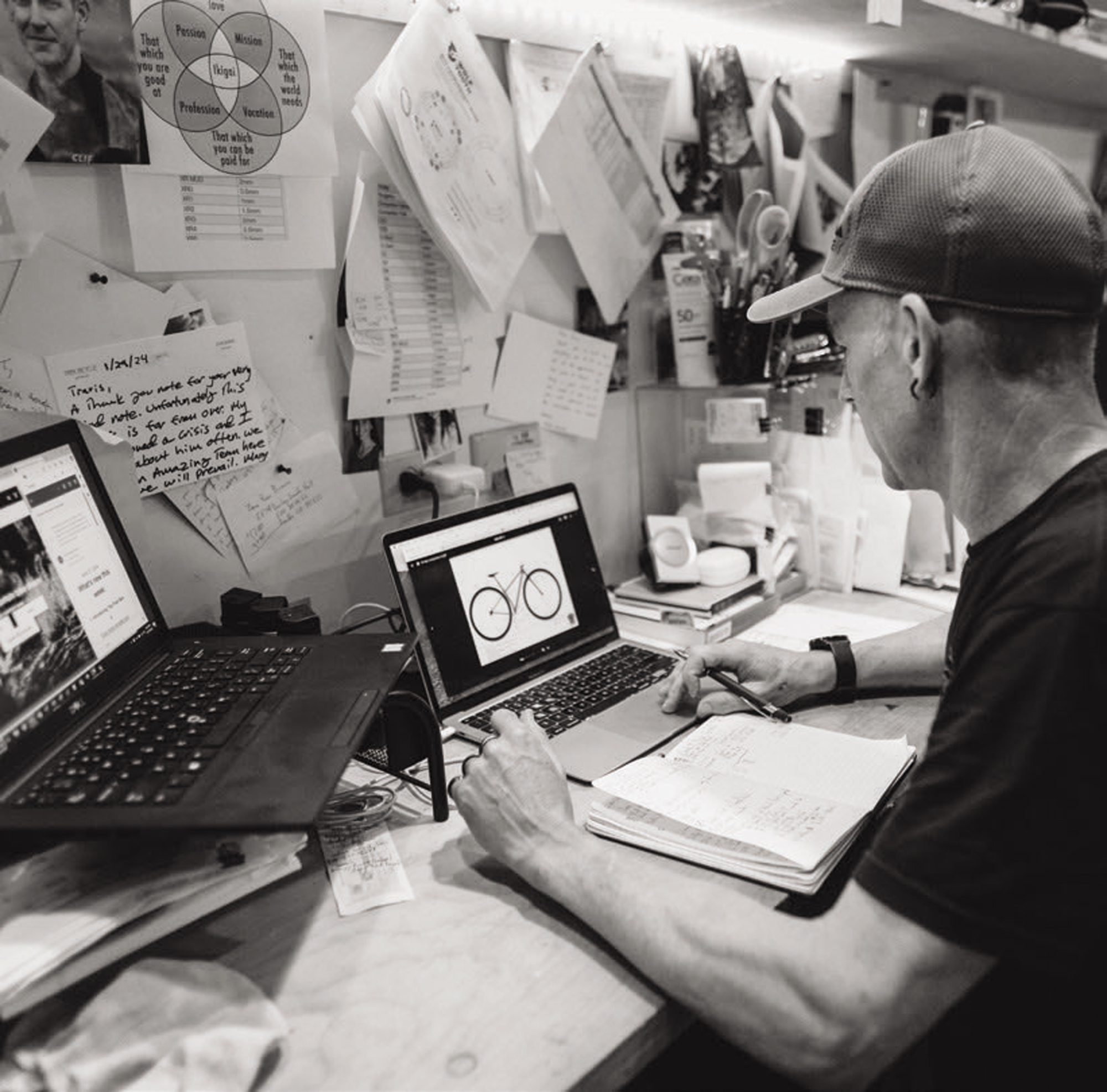

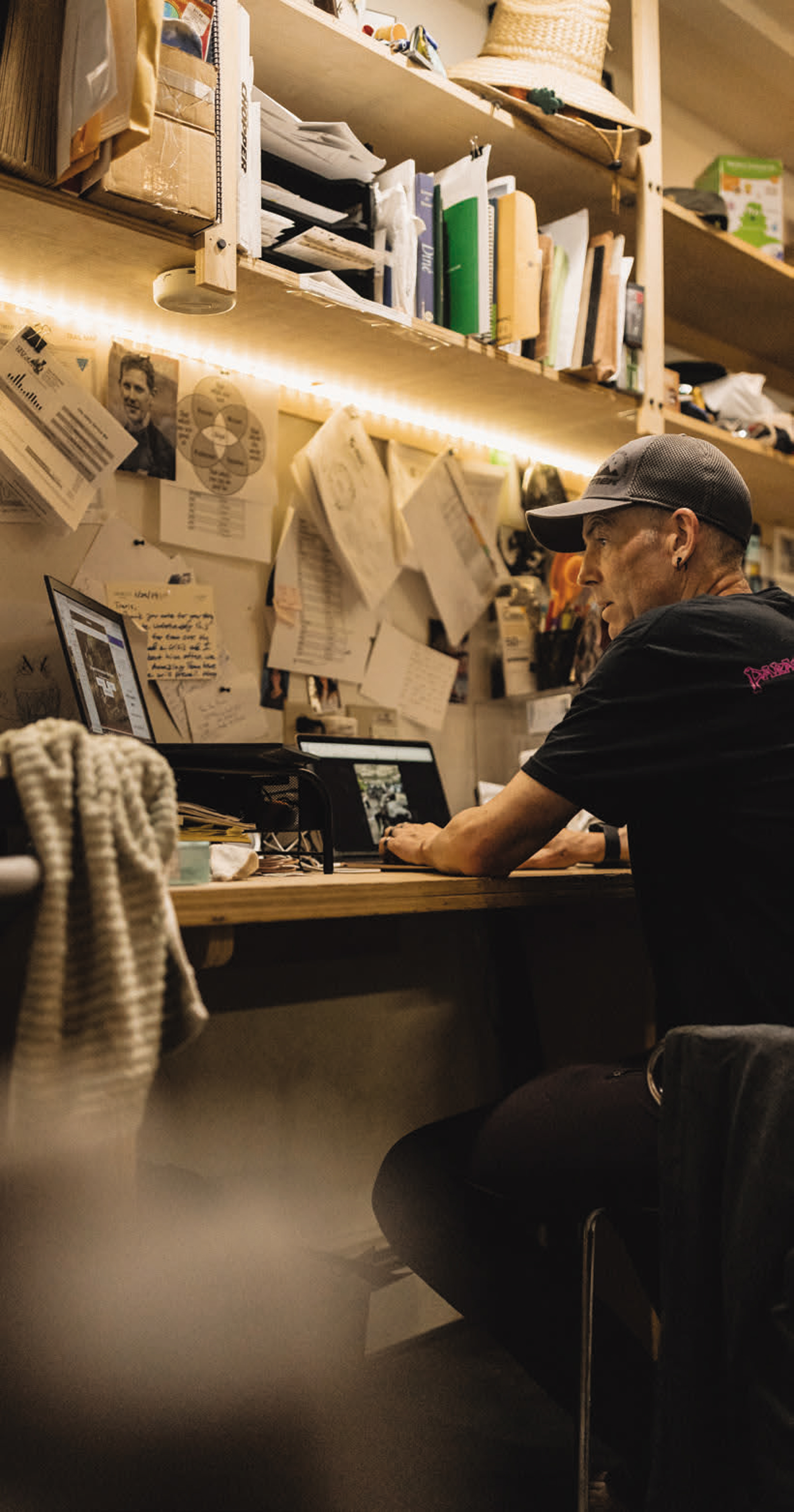

Foundations with Lachie Stevens-McNab

WORDS BY Lester Perry

IMAGES BY Cameron Mackenzie

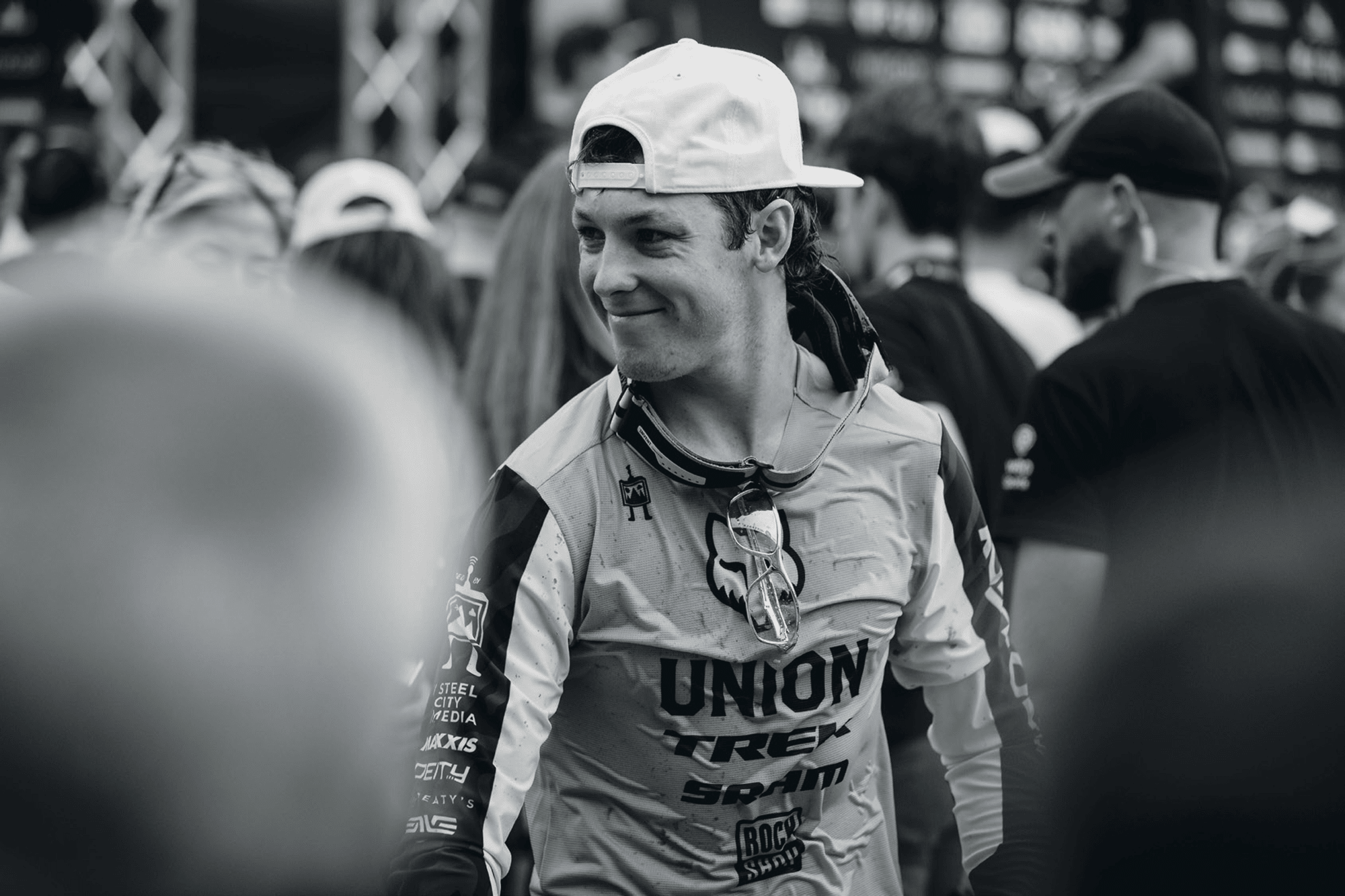

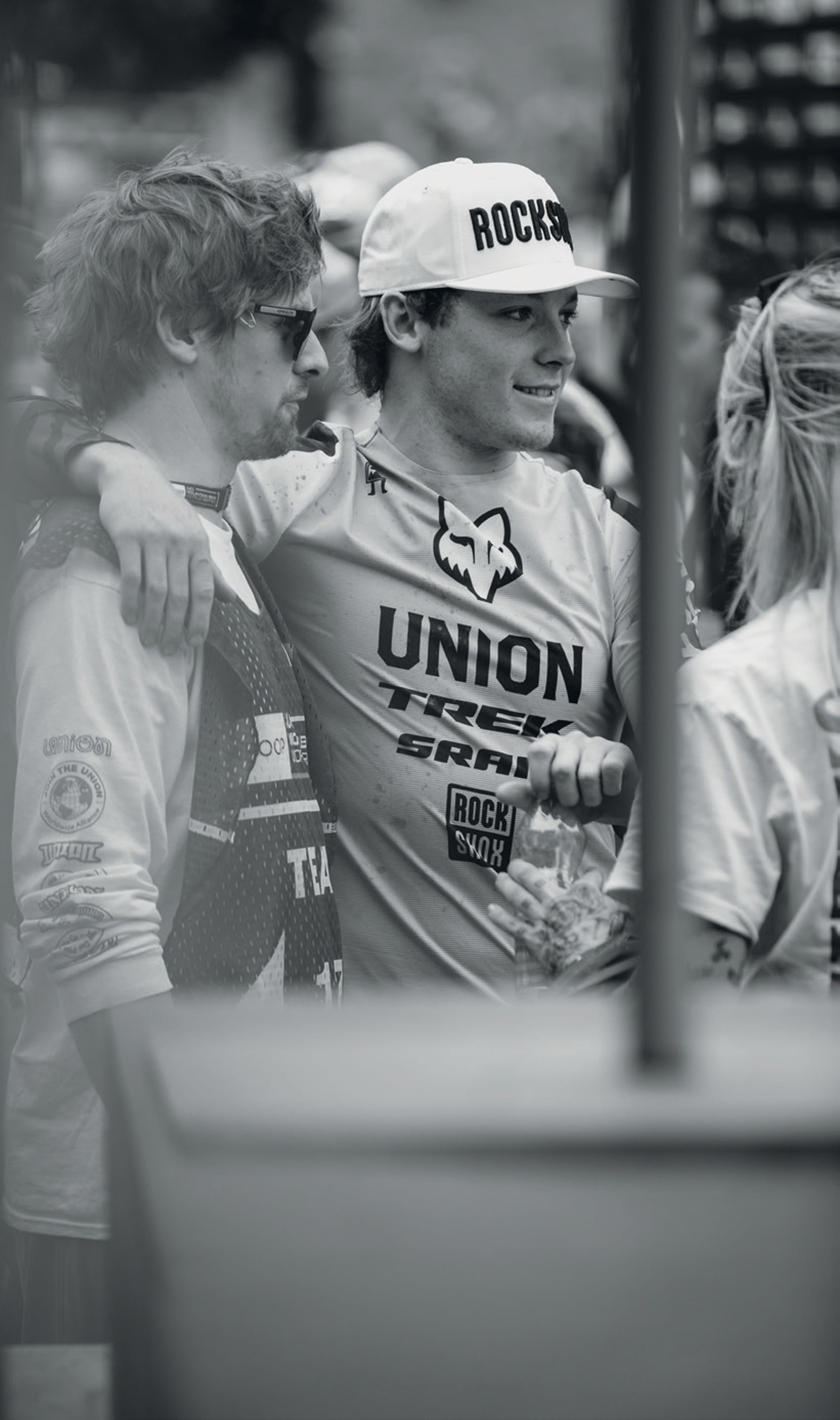

For Lachie Stevens-McNab, the 2024 downhill race season was one of highs and lows, learnings and triumphs, as he set out to cement himself as a consistent podium contender.

Foundations are critical to any successful pursuit; build a house without a sound foundation, and it won’t last long; build fitness without a base, and it’s quickly lost; and build a career racing downhill without a firm foundation of skill and mental fortitude, and it’ll be over before it’s begun.

Lachie had come into his twenties with a firm foundation. Firstly, a robust and supportive family built a foundation for him to springboard into a childhood pursuit of BMX world championships. His interest in BMX was piqued after spotting the Te Ngae Road BMX track in Rotorua while driving past one day. From that day forward, BMX was his focus, and Lachie and his family were regulars at gate training nights, and toured the country racing the NZ circuit.

Lachie’s success in BMX didn’t come quickly, but once the tap was opened, race wins flowed. World titles began at age six in South Africa, followed by more at ages seven and nine, alongside three second places. His last BMX World Championship in Auckland, at the UCI BMX World Championships in July 2013, aged nine, was a special one—clinching the win from Connor Defrain (USA), who’d pipped him for the win the previous year in Birmingham (UK).

Joe Bowman, the owner/manager of Lachie’s current team, ‘The Union’, comments: “He’s got an amazing family. I think they’ve just brought him up really well, and he’s confident in his abilities, but also with BMX racing—that he obviously did a ton of when he was younger—and winning world championships, and dealing with the stress and pressures from such a young age, you can see it in him now that he’s at peace with it.”

As his competition sprouted and he grew physically stronger, Lachie lagged, becoming one of the smaller riders in his age bracket. “Everyone was growing heaps in BMX and, as you know, the starts are so important, and I just couldn’t get a good first straight. My track speed was always good, I would always be there, but those other kids were just getting way bigger than me. And so I just couldn’t really compete. I was just pretty over it. I love BMX, to be honest. It was sick. I do miss the head to head stuff.”

Frustration grew, and unsatisfied with his training not converting to wins, Lachie began spending more and more time riding the Whakarewarewa trail system, literally a stone’s throw from the Rotorua BMX track.

Lachie never “quit BMX”, but the trails were calling and, slowly, he began to spend more time on a mountain bike than a BMX.

“I was just riding mountain bikes for fun with my mates at the weekend. Originally, when I first started riding mountain bikes, I wanted to do slopestyle—I loved Brandon Semenuk— but I realised pretty quickly that it wasn’t what I wanted to do,” explains Lachie.

When Crankworx came to town in 2015, Lachie immersed himself in downhill culture, watching the best in the game race the Ngongotaha downhill. He caught the bug and knew what he wanted to do. “I met Loic Bruni and then all the Kiwi boys too, when Crankworx came to Rotorua, while watching that downhill. I got a downhill bike not long after that. Do you remember that big tabletop they had at the bottom of Skyline? I pushed up the hill, and was trying to jump that, cause I’d just been watching Georgie B (George Brannigan) and Brook (Brook MacDonald) ride it. So I was frothing. I was 14 when I was like, oh yeah, I want to race World Cups.”

Thanks to the shuttle-accessed downhill tracks in Rotorua, Lachie’s progress on the MTB was rapid compared to some, but he wasn’t a standout immediately. His first couple of years racing downhill were nothing exceptional and a steep learning curve. By 2019, Lachie was taking downhill seriously, and BMX was on the back burner. “My dad took me to the Oceania Champs in Bright, Australia. I got smoked; that was my first year Under 17. It was a good weekend if I was a top five in my first year Under 17.”

A year of racing and a growth spurt later, Lachie’s second year in Under 17 was better and he started doing well in New Zealand during that time.

Spring forward to 2021 and, like most Kiwis chasing the World Cup dream, Lachie began his European racing chapter travelling in—and living out of—a van with Alex Wayman and Finn Hawkesbury-Brown. Thanks to downhill’s tight-knit community, Lachie and “the boys” managed to get themselves out of numerous sticky situations and gain some valuable experience and some solid finishes with podiums across World Cups, Crankworx and IXS downhill events early in the season, capped with a third place at the World Championships.

In typical Kiwi “make-do” fashion, Lachie ran the gear he could make work best for him. “I went over on a Transition TR11 that I’d just got. It was a 27.5 wheeled bike. I just put a Fox 49 (fork) on it with a 29” wheel, slid the stanchions right through to get the head angle right. I took my forks to Fox and they were like, ‘what the heck are you doing? You’re bashing your seals to bits!’ I’d pulled my forks too far through, so each time I bottomed out, I’d hit the seals on the crown.”

For 2022, Lachie joined The Union under the watchful eye of owner/manager Joe Bowman: “I think he’s got that funny, menacing, just slightly loose Kiwi side, which we all kinda know and love, and I think some of the older Kiwi riders on the circuit have been known for that too. On the flip side, he’s super thoughtful, much smarter than people give him credit for; a dude who’s super caring and is very loyal as well.”

Aboard a new bike and with a new team environment, early 2022 brought Lachie an NZ Under 19 overall National Series win and another National Championship on home turf before returning to Europe for the World Cup season. Beginning strongly, Lachie opened his 2022 UCI World Cup account with a fourth place in the opening round in Lourdes, France. He backed this up at round three in a muddy Leogang (Austria), going one better to stand third on the box. On to round four in Lenzerheide (Switzerland), going one better into second place, Lachie was rapidly cementing himself as one to watch. Andorra didn’t go his way, a bit off the pace, but still a top ten finish, in eighth position. Lachie wrapped up his World Cup season with a pair of fourth places in Snowshoe (USA) and Mont-Sainte-Anne (Quebec, Canada), his consistency putting him in third overall for the 2022 World Cup series.

Joe adds, “I think Lachie is quite simple in the sense that he never asks for anything; he’s the opposite of a diva, and over the years—almost to a fault—he’s never asked for a single thing, even this year when he is challenging for the win, there’s never an ounce of, ‘I need this, I need that’, no dramas or anything. He just cracks on, and I think that’s a massive strength for him. The biggest strength he’s got over most other racers is that he’s so mentally strong, and I think that’s part of it; that’s his personality. He’s mentally strong in general, and I think that carries into his racing and is why he’s been so good this year, he’s always been there. He’s just had numerous brutal injuries because he’s been a bit loose on the bike. He’s reined that in now, and this season it’s all clicked.”

World Champs 2022 in Les Gets (Fr) was a pivotal moment for Lachie; a massive crash during qualifying left him with a snapped and displaced radius and ulna, and a broken T8 in his back. Not only did this put him out of that race, but started a run of bad luck and injuries. “That was over the bars, out of the roots; I just ejected out the front. That was huge. I broke my back, broke my wrist. Two weeks in hospital, in France. My mum had never come to a race, and then she came over for one, and that was the race!

“I was in this big back brace for a fair while, like three months, it was this big corset I was in day and night—I could only get out of it to shower. I had to be super careful of how I was sitting or how I’d stand up. I just had to be super still. So that was like day and night for two months. After two months, I could finally sleep with it off.”

Then 2023 was another season of discontent. Having recovered enough to get back on the bike just weeks prior, Lachie was easing back into things at the Christchurch round of the NZ National Series and got caught out by a rock hidden in the infamous moon dust of the Christchurch Adventure Park’s GC trail. Another over the bars incident, another broken wrist and a period off the bike before launching into the 2023 World Cup season, his first in Elite.

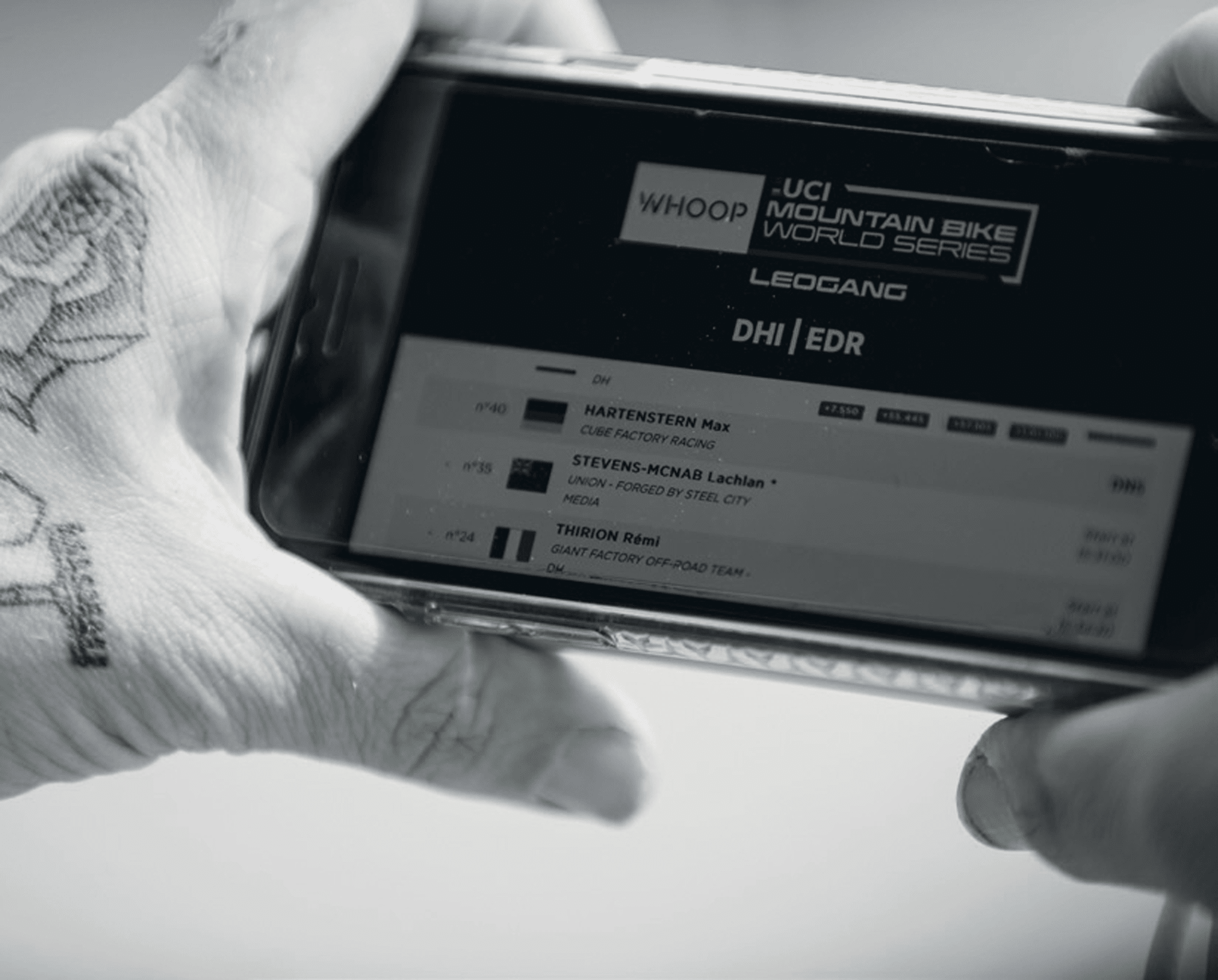

Lenzerheide kicked things off for Lachie’s Elite career. A 26th place after months of adversity was a small comfort, considering his pace the previous year. But 2023 didn’t get much better for him, unfortunately. He crashed in qualifying at the following round in Leogang, then crashed while training in Schladming a week later, blowing his ankle up. Bone bruising and ligament issues plagued the remainder of his season. With his The Union contract coming up for renewal at the end of the year and no guarantee they would continue into 2024, Lachie knew he needed to get back to racing asap. “I tried to come back for Snowshoe and Mount Sainte Anne. I couldn’t even ride Snowshoe. And at MSA, I crashed in qualifying.”

Regardless of the uncertainty and Lachie’s injuries, The Union committed to Lachie, and although they didn’t have all their ducks in a row for 2024 they were keen to keep him on the squad. “Joe said to me, yeah, we’ll keep you on. I’m pretty lucky with Joe—he’s the best dude I could have met. He didn’t need to keep me on—and if he didn’t, maybe I’d just be working for the old man now. So now I’m pretty lucky with Joe and that team,” says Lachie.

Joe adds; “After two years of brutal injuries, he’s basically just put his head down, worked even harder, and come out swinging this year when everyone had forgotten about him. I think people had written him off to be honest, and it’s been the sickest thing ever to watch him do his thing—and it just proves, I think, that just having the right environment and giving people time is key. It’s like not every rider just comes out swinging and wins everything in Junior, and Lachie’s the perfect example of that. It’s what The Union’s always been about, same with Antoine Pierron, Ollie Zwar, Tuhoto-ariki Pene, there’s been a few, Ollie Davis as well. Lachie’s just the next in line for that.”

As 2024 dawned, Lachie put the injuries and uncertainty of 2023 behind him. Joe had pulled together support for The Union, and it was all systems go heading into the new year. After an off-season of rehab and solid training, Lachie came in hot. At the opening round of the NZ National Series, in Whangamata, he bested second placed Sam Gale by almost eight seconds on a course with tight times. His dominance continued through the remainder of the NZ season, laying waste to the field across the remaining rounds in Rotorua, Christchurch and Cardrona.

In late February, NZ’s finest clashed with international favourites at the NZ Championships. The infamously one-lined, fast-paced track means tight times; a tiny mistake can cause a racer to tumble down the results sheet quickly. Lachie kept his winning ways rolling, heads were turning, and his name was on everyone’s lips come the end of the NZ season.

The Whoop UCI World Cup season kicked off in Fort William, Scotland, in early May. After qualifying in 18th position, stoke was high as Lachie headed into the semi-finals. An unfortunate broken chain as he headed into ‘the Motorway’, a critical section where having a chain was vital, put him back in 37th position. It was a frustrating start to the season, but the signs were there that his pace was where it needed to be.

Round two in Szczyrk, Poland, was another key moment in Lachie’s evolution towards being a top-level racer. He built on a qualifying result of seventh, finishing fifth in semis. Finals run was one to remember. Every race fan around the globe will have been sitting on the edge of their seat. Aggressive but controlled, Lachie was up by 1.4 seconds at the final split, and everything pointed towards a win… until it didn’t. A rapid washout of the front wheel put his dreams of a win on hold. I’d imagine everyone watching the race, regardless of who they were rooting for, would have had a lump in their throat after that rollercoaster of a run. It will go down with infamy as one of the “almost” runs of the season.

“It’s just a matter of time. I was gutted after Poland but, at the same time, I was seventh in qualifying and fifth in semis. I was at the top (waiting for finals), and Amaury Pierron was warming up just there, and I was a bit mind- blown. I was nervous, but I was just trying to enjoy the moment. I know now what a winning run feels like. I haven’t had another run like that this year. As much as I could have had a World Cup win. I think it was like, ‘I’ll come back and try again.’ It’s just as it is. I’m not too gutted; it was a cool experience to finally have that pace.”

Joe shares thoughts about Lachie’s Polish performance: “He was seventh in qualis, fifth in semis, and then nearly won finals and crashed, and I was kind of worried. I was like, oh man, is that going to fry his head, and is he going to try and push too hard for the rest of the season? But instead, he just came out swinging straight away at Leogang and got that first podium, and he’s kind of backed it up since then, which is the coolest part because consistency is the hardest thing about racing.”

Three seconds, that’s how close he was to a win at round three in Leogang. A solid weekend peaked in finals as, once again, Lachie had everyone on the edge of their seats. Third place and his first Elite Podium!

Val-di-sole, Italy, was the next stop for the World Cup circus. Unfortunately, after a tenth in qualifying, the “black snake” bit hard, and a bent rear brake rotor in Semis put an end to his dream of continuing his podium streak, finishing in 32nd, just missing the top thirty cut-off for finals. Easing the frustration but also stoking the fire for upcoming races was seeing team mate, Ellie Hulsebosch win her first World Cup. On to the next one! Les Gets, France, was next up. Heavy weather impacted the finals after sunshine and prime conditions through practice, making an unpredictable and sketchy course by the time Elite Men started their day. What played out was one of the toughest World Cups in recent memory, with almost everyone struggling to stay on their bike at some point during their run. The “impossible corner” claimed more than a few top-tier riders. Lachie kept things somewhat under control, going 12th in qualifying, 13th in Semis, and then rounding out the weekend with a solid 11th place after a wild weekend.

The 2024 UCI World Champs took place in Pal Arinsal, Andorra, at the end of August. A blazing fast track greeted riders and, with speeds high, times were tight. Lachie built speed over practice and qualified 19th. In his first attendance at a World Cup, Lachie had his dad up on the hill checking lines for him and, while charging down a high-speed section, Lachie’s front wheel went from under him, driving him to a dead stop, headfirst into a stump on the trail—right in front of his dad! It was a brutal impact. This easily could have been the season over for him, but he recomposed for the final and ended up 16th in his first Elite World Champs.

Wild weather played its part again, this time for round six in Loudenvielle, France, a week after World Champs. Riding a high, Lachie pinned his qualifier, taking the fastest time through the last split, ending up qualifying in the ninth spot despite harsh conditions. Into finals, Lachie was looking good, but a small off-track excursion in the slippery conditions cost him dearly, pushing him back to 29th. He ended up third at the second split after the race finished, and in he was running third in the split which he’d crashed. What could have been!

Jumping the ditch over the US to finish his season, Lachie was hungry; there was no question his speed was there, he just needed the puzzle pieces to fall into place. Come ‘The Fox US Open of MTB’ in Vermont, they finally did. A dominant performance saw him win qualifying and the final, taking the podium’s top step amongst a field of high-performers. After a ‘shoey’ on the podium, his focus quickly switched to the final round of the UCI World Cup the following week—and his last chance for a World Cup win in 2024.

Mont-Sainte-Anne, Quebec, is an infamous track known for its sketchy rock sections where one wrong move could send you over the bars and into the hospital. Qualifying was a write-off after a red flag on the course bu, fortunately, having now moved up the rankings to have a protected status, Lachie automatically made it into the semifinals. Taking a relaxed approach, and trying to stay chilled through the gnarly sections, Lachie slid into eleventh in the semifinals. He had more to give come finals. Surviving the greasy, unpredictable sections, he hooked into second place, his highest World Cup finish and proof that he was now a safe bet for a win when the time came.

“To be that close to the win was pretty unreal, I couldn’t believe it. It was a really good run. It was solid. There were some little mistakes, just a little bit offline, and there were some bits that were pretty greasy. So, for how greasy it was, it was really good. But it wasn’t like my Poland run. I felt what the winning run feels like in Poland; it was unreal how it felt there, but Mont-Sainte-Anne wasn’t that.”

Joe sums up where Lachie is currently: “I think his mentality is key as well; he still has fun and is not just a boring racer. You could call it the pub rule— you’d still go for a beer with him, wouldn’t you? You can’t say that about all the riders, especially these days, so I’m beyond proud of him. He’s a mate, and I can’t wait to see what he does going forward; now he’s going to have proper factory support (for 2025) and he’s only just getting going, you know, at 20. I honestly believe he’s going to win a World Cup next year and be a challenger for years and years to come, so I’m excited to see it.”

In the grand scheme of things, Lachie’s career has taken a hockey-stick-like trajectory, going from the sketchy grom I remember sitting in the front of the Rotorua shuttle bus, his signature dreads poking out from under his full-face helmet, to a more clean-cut pro- racer with his head screwed on—one who there is no doubt is destined for greatness.

If he’s achieved so much in such a short timeframe, what can he achieve in that same period of time over the coming years? One thing’s for sure: race fans worldwide will be watching.

It's Robin's World (we're just living in it)

Words Kerrie Morgan

Images Cameron Mackenzie, Red Bull Content Pool – Paris Gore, Robin O’Neill, Emily Tidwell, Bartosz Wolinski, Long Nguyen

If you haven’t yet experienced the thrill of watching Robin Goomes drop in down a 12.5m (41ft) rock face to win this year’s Red Bull Rampage, do yourself a favour and put this magazine down right now; pull out your phone and open YouTube.

Once you’ve watched it, you’ll be asking; “So, why weren’t women able to compete at this event until 2024??” It’s a mind-boggling question, especially after watching Robin and her badass brethren of equally-capable women flip, whip and speed their way down the red, rocky, tumble-weed-dotted surface of the Virgin, Utah desert. Despite launching riders off of cliff faces since 2001, the infamous Rampage has just included women for the first time this year. Yes, 2024. Previously, the idea had been discarded under the pretence of it being too physical, too gnarly, too unwieldy for a woman to handle.

However, in October 2024, Robin along with Casey Brown, Vinny Armstrong, Camila Noguiera, Vaea Verbeek, Vero Sandler, Georgia Astle and Chelsea Kimball proved any naysayers wrong, flipping (literally) the narrative and securing female free riding’s position, at the most extreme level, on the global stage.

But Robin’s story doesn’t begin there. Believe it or not, Rampage is just another string to the 28-year-old’s bow. Starting out life on the Chatham Islands, some 800km off the coast of Christchurch, Robin’s childhood in the isolated, tightknit community was the perfect grounding for a life of adventure, determination and success.

In the early days, Robin tore around the island on dirt bikes with a crew of guy mates who were of the opinion; “she wants to ride motorbikes—great, let’s go!” It was only natural that more serious riding later followed suit.

“I think I was really lucky in the beginning. That space was so easy to be in, it was really normalised, and it didn’t matter that I was a girl riding a dirt bike,” explains Robin.

Having left the island for high school, Robin took up mountain biking when she was in the Army, thanks to encouragement from a group of riding friends who, as Robin puts it, “were also all dudes”. She explains that finding guys to ride with, who couldn’t care less about what your gender is, is the key to a positive experience.

“When I did eventually face negativity, it didn’t matter anymore, because I’d already done so much,” says Robin. “It was just like, ‘whatever dude’. The positive felt like it was stronger than the negative, for sure.”

Since taking up mountain biking, everything has snowballed for Robin and, these days, she’s not only the inaugural women’s Red Bull Rampage winner but can also claim the title of ‘first woman to land a backflip in a Crankworx competition’; was featured in the Red Bull film Anytime; and competed in Red Bull Formation in 2022—to name just a few accolades.

Robin credits her island upbringing, and her role in the Army, for the resilience, determination and confidence she relies on today as a professional mountain biker. “It definitely has helped,” says Robin. “I don’t exactly know where it has helped, but it definitely has. I think growing up on the Chatham’s was the craziest place to be brought up. I went back recently, and it is just so far away! If you want New Zealand to feel really big, go to the Chatham’s. Growing up in a place like that gives you good drive [so that] when you do get an opportunity, you definitely want to take it. That type of upbringing can take you anywhere really, but it feels like the start line was so much further back for me than for most people. And then with the Army—so many good skills were learnt there and, without that, I’m not sure where I’d be.”

Being the first woman to drop in, from the first cohort of women to ever compete at Rampage, was not Robin’s first or only foray into paving the way for other women. During her time in the Army, she was one of the only women to be based out at Scott Base as a machine operator. It seems that leading the charge comes naturally to this humble Kiwi.

“It hasn’t been a conscious goal of mine,” confesses Robin. “But I think with the stuff I like to do, I always end up working in these male dominated spaces. What I learnt—especially from the Army—is that, as a female working in a male dominated space, you have to work (what feels like) twice as hard just to keep up. So I guess taking that into anything I’m doing is the goal.”

No doubt some of the skills Robin has gained throughout her life so far came into play when she was waiting in the start gate, anticipating her drop in at Rampage. “I kind of just treated it like any other competition, where you just try to visualise your run, step by step, one feature at time, focusing on the main points, like where you can take a moment to reset yourself and go again, what tricks you really need to dial in, braking points. All of those little details were really all I was thinking about,” explains Robin. “Then there was a moment when I was in the start gate, with the starter, Darren—he’s started every single Rampage I’m pretty sure, he’s iconic—and when you’re sat in the start hut and they call your name, and they’re like ‘rider dropping!’ and they count you in… I just kinda had a laugh to myself. I thought, I am literally watching this on TV—but I’m doing it. It was quite a surreal but cool moment.”

Robin credits some of her cool-as-a-cucumber approach to the fact that she designed and dug the lines she would be dropping into that day.

“It’s cool because you can kind of decide how big or how small you want to go,” she explains. “But when you’re looking at a completely empty hill—a full blank canvas—it’s kind of overwhelming and it can be hard to know if you’ve gone too big or too small at the time. Until you start building, you’re not really sure if you’ve gone too big or if it’s even possible… You have about a day where you’re like, ‘Oh, maybe I’ll back out of this’ and after that you’re locked in, and you just have to do it, and you have to find a way to make it work. You can choose to go bigger or smaller, but I just really wanted to try and find the limits, where the edge was of what was possible with my comfort zone. I was trying to go big.”

And big she went.

But, we all know that what goes up, must come down—and free riding is no different. Human beings weren’t designed to fly and, for the brave few who do choose to throw themselves off of cliff faces attached to a bike—for fun— there can be serious consequences. But what is less talked about is the massive comedown extreme sportspeople often feel post-event or milestone. Robin’s ride—and success—at Rampage saw her struggle to merge back into “normal life” once the event wrapped.

“Recovering from other events is pretty standard. This one was very different,” she explains. “Rampage feels like an endurance event. It’s not just like you turn up, you do a few days practise and then you compete. You build it, so mentally, physically, you’re just ruined—and then you’re competing. It was two weeks long, basically, of really high intensity stuff. Then the comedown was unbelievable. It was probably the greatest moment of my life—I don’t know how I’m ever going to top it—so I guess coming home and just doing normal stuff for a bit…. I definitely struggled with this one. It felt super extreme, and it was weird—I’d just done the coolest thing ever and then I came home and was just mowing the lawns one day, like, I don’t even know what’s going on anymore?!”

Robin explains that the feeling is the same with any other event, just on a much smaller scale. “I think that is literally part of the ride, though—when we sign up to do these things, I think that’s the full journey, it’s not just the one piece you see on a live stream… it’s all of that stuff; the before, middle and end.”