Paradise Found: New Caledonia

There are places that exist in your peripheral vision, destinations you’ve heard whispered about but never quite focused on. New Caledonia was one of those places for me. A French territory floating in the South Pacific, closer than you’d think yet somehow still undiscovered by the masses that flood more predictable island escapes.

I’d be lying if I said the draw was purely romantic. Sure, the promise of lagoons so impossibly turquoise they look Photoshopped played a part. But what really caught my attention was something unexpected: mountain biking. Proper, technical, lung-burning mountain biking on a tropical island. The kind of riding that makes your quads scream and your mind go quiet.

And here’s the thing that sealed it: getting there from New Zealand is absurdly easy. Three hours from Auckland with Aircalin, and suddenly you’re stepping off a plane into French Polynesian warmth, where the croissants are legitimate and the trails are waiting.

A Territory Still Finding Its Feet

I need to address something before we go further. New Caledonia is recovering. In 2024, civil unrest shook this island, tensions boiling over around questions of independence and identity that have simmered for decades. It wasn’t the paradise-postcard story tourism boards want to tell, but it’s the truth, and ignoring it would be dishonest.

The violence has subsided. The streets of Nouméa, the capital, have found their rhythm again. But the scars are still visible if you know where to look, and the path forward remains uncertain. Some might see this as reason to stay away. I see it differently.

Tourism matters here. It employs people. It sustains communities. It gives young Kanak locals opportunities beyond subsistence. Visiting now, with eyes open and respect intact, isn’t exploitation – it’s engagement. It’s choosing to see a place in its complexity rather than demanding it perform simplified paradise for your comfort.

So yes, I went. And I’d go again.

The Proximity Problem (Which Isn’t Actually a Problem)

Here’s what surprises most people: New Caledonia is genuinely close. Not “close for the South Pacific” close. Actually close. Three hours from Auckland. Three hours from Sydney. Two hours from Brisbane. The flight on Aircalin is the kind where you board with a coffee, read a few articles, maybe watch half a film, and then you’re descending over that absurd lagoon.

I remember looking out the window during final approach, seeing the reef system from above – this massive natural barrier protecting the main island like a turquoise moat. It’s UNESCO-listed, apparently one of the longest barrier reefs on the planet. From 10,000 feet, it looks painted on.

La Tontouta International Airport sits about 45 minutes outside Nouméa. I’d arranged a car through Europcar, and within an hour of landing, I had a bike rack strapped to the roof and the windows down, driving toward accommodation with that specific kind of excited exhaustion that comes from crossing into somewhere new.

Where the Riding Lives

Let’s talk about why you’d bring a mountain bike to a tropical island. New Caledonia has a network of trails that would make most dedicated riding destinations envious. They’re technical without being punishing, scenic without sacrificing challenge, and crucially, they’re accessible.

Parc des Grandes Fougères

The name translates to “Park of the Great Ferns,” which undersells it considerably. This is rainforest riding – dark, humid, technical. The trails wind through ancient tree ferns and native kauri, cutting lines through terrain that feels genuinely primeval. It’s not a massive network, but what’s there is quality. Expect roots, expect rocks, expect your brakes to work overtime.

Domaine de Deva

This is where things get serious. Domaine de Deva hosts the DEVA100 race every June, a two-day endurance event that attracts riders from across the Pacific. Even if you’re not racing, the trails here are worth multiple visits. They range from flowy XC loops to proper technical descents, all threaded through West Coast landscapes that alternate between dry scrub and sudden green.

The Deva100 race itself runs June 27-28 in 2026, and if you’re the kind of rider who likes suffering in beautiful places, I’d recommend registering. The event has that slightly chaotic, under-commercialized energy that makes regional races memorable.

Blue River Provincial Park

If Domaine de Deva is serious, Blue River is sublime. This park sits inland, away from the coast, in terrain that feels closer to New Zealand backcountry than tropical island. The trails here are varied – some technical, some fast, all rewarding. And in October, it hosts the Perignon MTB race, another two-day event scheduled for October 10-11, 2026.

I rode Blue River on a rest day between training sessions, just exploring. There’s something about riding in a place with no pressure, no GPS track to follow, no Strava segment to chase. Just you, the bike, and trails that lead somewhere you haven’t been. I ended up at a viewpoint overlooking the valley, legs buzzing, lungs full, completely alone. It’s the kind of moment you can’t manufacture.

Tina’s Bike Park

Right in Nouméa, Tina’s offers accessible riding without needing to drive anywhere. It’s more park than wilderness,

but the trails are well-maintained and perfect for warming up or cooling down. If you’re staying in the city and want to spin the legs without committing to an expedition, this is your spot.

Netcha

Netcha is quieter, less developed, and frankly, a bit of a hidden gem. The trails here feel more raw, less curated. If you’re the type who prefers discovery over convenience, carve out a day for Netcha.

Base Camp: Ramada Nouméa

I stayed at the Ramada Hotel in Nouméa, which proved to be exactly what a riding trip needs: clean, central, functional. It’s not boutique. It’s not trying to be. What it is, is well-located, with staff who didn’t blink when I asked about bike storage and seemed genuinely interested in where I was planning to ride.

The hotel sits close enough to the city center that you can walk to cafes and restaurants, but far enough from the main strip that you’re not drowning in tourist noise. After long days on the trails, I’d return, shower off the dust and sweat, then wander down to Anse Vata beach to watch the sun drop into the Pacific while nursing a beer.

There’s something deeply satisfying about that rhythm: ride hard, eat well, sleep deep, repeat.

The French Factor

New Caledonia is French. Not French-influenced. Not French-themed. Properly, administratively French. The currency is the Pacific Franc (CFP), which stays pegged to the Euro. The language is predominantly French, though you’ll find English speakers in tourist areas and among younger locals. The food is – and I say this with full appreciation – absurdly good for a place this far from Paris.

Bakeries serve actual croissants, the kind with proper lamination and that slightly yeasty smell that makes you instantly hungry. Restaurants take food seriously without being pretentious about it. Wine lists feature French imports at prices that would make Australians weep.

This creates an interesting cultural overlay. You’ve got Melanesian culture, indigenous Kanak traditions, French administrative systems, and a growing population of immigrants from Wallis and Futuna, all coexisting in this small archipelago. It’s not always seamless – the recent unrest proved that – but it creates a texture you don’t find in more homogenous destinations.

Beyond the Bike

Look, I went for the riding. But pretending that’s all New Caledonia offers would be disingenuous.

The lagoon is legitimately stunning. Snorkeling and diving here rank among the best in the Pacific. The reef system

supports an ecosystem that includes dugongs, sea turtles, and enough tropical fish species to keep marine biologists

busy for careers. You can kayak through mangroves, kiteboard in protected bays, or just lie on beaches that see a

fraction of the traffic Hawaii or Fiji deal with.

Île des Pins, “Isle of Pines,” sits southeast of the main island and offers that postcard-perfect island escape if you need a counterpoint to all the technical riding. Traditional Kanak culture is more visible here, and the pace slows to something approaching stillness.

But honestly? I kept thinking about the trails.

The Logistics

Getting there is straightforward. Aircalin flies direct from Auckland, Sydney, and Brisbane. Three hours, three

hours, two hours respectively. Pack your bike, check it as luggage (Aircalin handles bikes without drama), and

you’re done.

Car rental is essential. Europcar has a desk at the airport and locations in Nouméa. Get something with decent clearance if you’re planning to access remote trailheads. Roads are generally good, but “generally” does some heavy lifting in that sentence.

Accommodation ranges from budget hostels to resort-level luxury. I’d lean toward staying in Nouméa as a base – it’s

central, it has infrastructure, and the Ramada there offers solid value without trying to extract every last Franc from

your wallet.

As for timing: June for the Deva100, October for the Perignon MTB, or frankly any time between April and November. The summer months (December-March) get hot and humid, with a higher chance of cyclones. Not unrideable, but not optimal either.

The Honest Assessment

New Caledonia isn’t perfect. It’s dealing with serious internal questions about identity, independence, and equity. Tourism infrastructure isn’t as developed as neighboring destinations. English isn’t universal. Prices can sting, especially if you’re used to Southeast Asian budgets.

But here’s what it offers: accessibility without crowds, world-class riding without the hype, cultural complexity

instead of resort-sanitized “authenticity,” and a landscape that manages to be both familiar and completely foreign.

I flew in on Aircalin on a Wednesday morning. By Thursday afternoon, I was waist-deep in the lagoon, bike leaning

against a palm tree, legs still vibrating from that morning’s ride through Parc des Grandes Fougères. By Saturday, I was mentally planning my return.

Three hours from Auckland. That’s closer than Queenstown. Closer than most Australian destinations worth

reaching. And somehow still flying under the radar of the mountain biking masses.

I’d suggest keeping it that way, but that seems selfish. And besides, places this good don’t stay secret forever.

Practical Information

Getting There:

Aircalin operates direct flights from Auckland (3 hours), Sydney (3 hours), and Brisbane (2 hours).

Website: https://www.aircalin.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/aircalinNC/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aircalin/

Car Rental:

Europcar has locations at La Tontouta International Airport and in Nouméa. Essential for accessing trailheads.

Website: https://www.europcar.fr/fr-fr/places/location-voiture-new-caledonia/noumea/noumea-centre-ville

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/EuropcarNouvelleCaledonie

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/europcar_nc/

Accommodation:

Ramada Hotel Nouméa offers central location, bike-friendly facilities, and good value.

Website: https://ramadanoumea.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ramadahotelnoumea

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ramadanoumea/

Mountain Bike Parks & Events:

• DEVA100 – June 27-28, 2026, Domaine de Deva

https://www.proevents.nc/evenements/deva100

https://www.nouvellecaledonie.travel/destination/cote-ouest/domaine-de-deva/

https://sitesvtt.ffc.fr/sites/les-boucles-de-deva/

• Perignon MTB – October 10-11, 2026, Blue River Provincial Park

https://www.proevents.nc/evenements/perignon

https://www.province-sud.nc/decouvrir-et-visiter/pprb/

• Parc des Grandes Fougères – Technical rainforest riding

https://www.province-sud.nc/decouvrir-et-visiter/ppgf/

• Tina’s Bike Park – Urban trails in Nouméa

https://www.sudtourisme.nc/offres/les-boucles-de-tina-noumea-fr-3005526/

• Netcha – Raw, less-developed trails

https://sitesvtt.ffc.fr/sites/les-boucles-de-netcha-6/

Event information: www.proevents.nc

Tourism Resources:

New Caledonia Tourism: https://www.nouvellecaledonie.travel

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nouvellecaledonieFR

Facebook (South Tourism): https://www.facebook.com/sudtourismenc

New Trail Guidelines

Words Meagan Robertson

Images Christian Wafer

What if being able to ride a Grade 5 in Rotorua meant being able to ride a Grade 5 in Nelson? And riders who rode Grade 3 Great Rides could confidently ride Grade 3 singletrack around the country? Well, that’s what the Trail Guidelines intend to achieve.

After months of research and review, the newly released New Zealand Mountain Bike Trail Design Guidelines have been released and are being distributed to trail builders nationwide, through Trail Fund. Updated by Recreation Aotearoa in partnership with DOC, Ngā Haerenga New Zealand Cycle Trails, ACC, and Sport NZ, the aim is to provide safer, more consistent, and more inclusive trail experiences to riders across the country by providing clear guidance for everyone involved in their design, construction, and maintenance.

Developed in consultation with trail builders, land managers, and riding groups nationwide, this third iteration of the guidelines includes everything from fine-tuned grading specs to new chapters on signage, auditing, safety, maintenance, adaptive access, and more.

The impossible task of updating the guidelines to the satisfaction of trail builders and mountain bikers across the country was led by Jonathan Kennett—who most will know from the Kennett Brothers long-time contributions to MTB grading and guideline development in Aotearoa.

“It was always going to be a challenge aligning different features into a single grade, because mountain biking is so diverse,” said Jonathan. “But I think where we’ve landed will please 99% of riders. The biggest change in the guidelines has been allowing steeper gradients and more features for downhill tracks, Grade 4 and 5 in particular, without those tracks becoming completely unsustainable. We’ve largely done this by adding new guidance for rollovers and chutes, which can be quite steep, so long as they have a reset section at the bottom.”

Why is the guidance needed?

The update comes in response to a Coroner’s recommendation to align trail safety guidance nationally, as well as mounting ACC injury claims. With over 5,500 injury claims and $22 million in ACC costs last year alone, ACC sees this unified approach as both timely and necessary.

A key step in unifying the approach was having the country’s two largest trail building organisations—DOC and Ngā Haerenga— on board. With DOC confirming it will transition to using the new guidelines, and Ngā Haerenga New Zealand Cycle Trails aligning its own specifications accordingly, the 2025 edition is a true national reference point—streamlining previously fragmented guidance into one accessible framework. “ACC is proud to support the updated guidelines, which are all about helping people enjoy mountain biking safely,” says Kirsten Malpas, ACC Public Health and Injury Prevention.“Consistent signage and trail grading helps riders choose the right trails for their skill level and reduces preventable injuries.”

Trail Fund invests in getting guidance in the right hands

“The Coroner’s recommendation is an admirable and valid request,” says Trail Fund co-president, John Humphrey. “But a monumental task for a trail system largely built by disparate volunteer groups around the country. That’s where Trail Fund comes in—we are the only national organisation liaising with trail builders around the country and we’repleased to be involved with this ongoing initiative.”

One of the key differences in this update is the addition of a Trail Builders’ Handbook, which offers trail crews a concise, field- friendly reference—complete with diagrams, benchmarks, and design dos and don’ts for each of New Zealand’s six MTB trail grades. These handbooks are well suited to be distributed by Trail Fund, which has carried out training for hundreds of volunteer trail builders over the past decade. The organisation is also well placed to encourage clubs to use them, especially those who receive funding from Trail Fund.

“We appreciate that every area and club is different, and trail builders collectively hold a broad range of skills and approaches,” says John. “However, we are confident those involved have done their homework and put forward high-quality guidelines that provide a robust framework for trail building around the country.

“This doesn’t mean the conversation is over. This is the third iteration of these guidelines, and we look forward to working with the trail building community on implementation to support the evolution of mountain biking and trail building.”

Trail Fund NZ will continue acting as a conduit between builders and Recreation Aotearoa, helping to channel on-the- ground feedback to ensure the guidelines stay relevant as the sport evolves.

What’s new?

This third edition builds on the earlier 2018 and 2022 versions. Key changes include:

Updated grading guidance:

Small but significant refinements have been made to gradient ranges, minimum widths, radius, and jump length specifications. These tweaks are intended to better align guidance with the realities of today’s trail construction and riding styles.

New chapters on signage and auditing:

For the first time, the guidelines offer detailed templates for signage and safety warnings, developed with input from the NZ Land Safety Forum. An auditing chapter is designed to help clubs and land managers assess trail conditions and confirm grade accuracy.

Improved safety design:

The safety chapter directly responds to coroner recommendations and ACC data. It introduces practical methods for designing fall-safe trails, assessing hazards, and mitigating risk without compromising rider enjoyment.

Stronger focus on inclusivity:

Building on the Outdoor Accessibility Design Guidelines released earlier this year, the guidelines provide specific direction for adaptive MTB trails, including grade specs and facilities for riders on three- or four-wheeled bikes.

New Trail Builders’ Handbook:

A complementary Trail Builders’ Handbook offers trail crews a concise, field-friendly reference—complete with diagrams, benchmarks, and design dos and don’ts for each of New Zealand’s six MTB trail grades.

What it means in practice

Over the years, trail riders have lamented how a Grade 5 trail in Rotorua differed from a Grade 5 trail in Nelson. Based on the newly published guidelines, here are the differences:

Grade 4 – Advanced

Track width 0.6–1.0m

Surface Mostly stable, but may include loose rocks or variability

Obstacles Up to 200mm high

Berms Up to 40°

Jumps 1–7 m long, 10°–30° ramps; all features must be rollable

Drops Up to 400mm, rollable

Uphill steps Up to 200mm

Concurrent features Up to 3 at a time

Risk Exposure possible; suitable for riders with excellent skills and experience

Grade 5 – Expert

Track width 0.4–0.8m

Surface Widely variable; roots, rocks, ruts common

Obstacles Up to 500mm high

Berms Up to 50°

Jumps 1–12 m; may not be rollable (b-line or bypass required)

Drops Up to 1,000mm

Uphill steps Up to 500mm

Concurrent features Up to 4 at a time

Risk Steeper, narrower, and more technical than Grade 4; higher exposure and consequences

Where to find the Guidelines

The full New Zealand Mountain Bike Trail Design Guidelines and the new Trail Builders’ Handbook are now available online at Recreation Aotearoa, Trail Fund NZ, DOC, and other partner websites. Printed handbooks are being distributed to trail building groups around the country via Trail Fund NZ.

To support understanding and adoption of the new content, Recreation Aotearoa is hosting two free webinars in late August—one for land managers and one for trail groups. Registration links are available online.

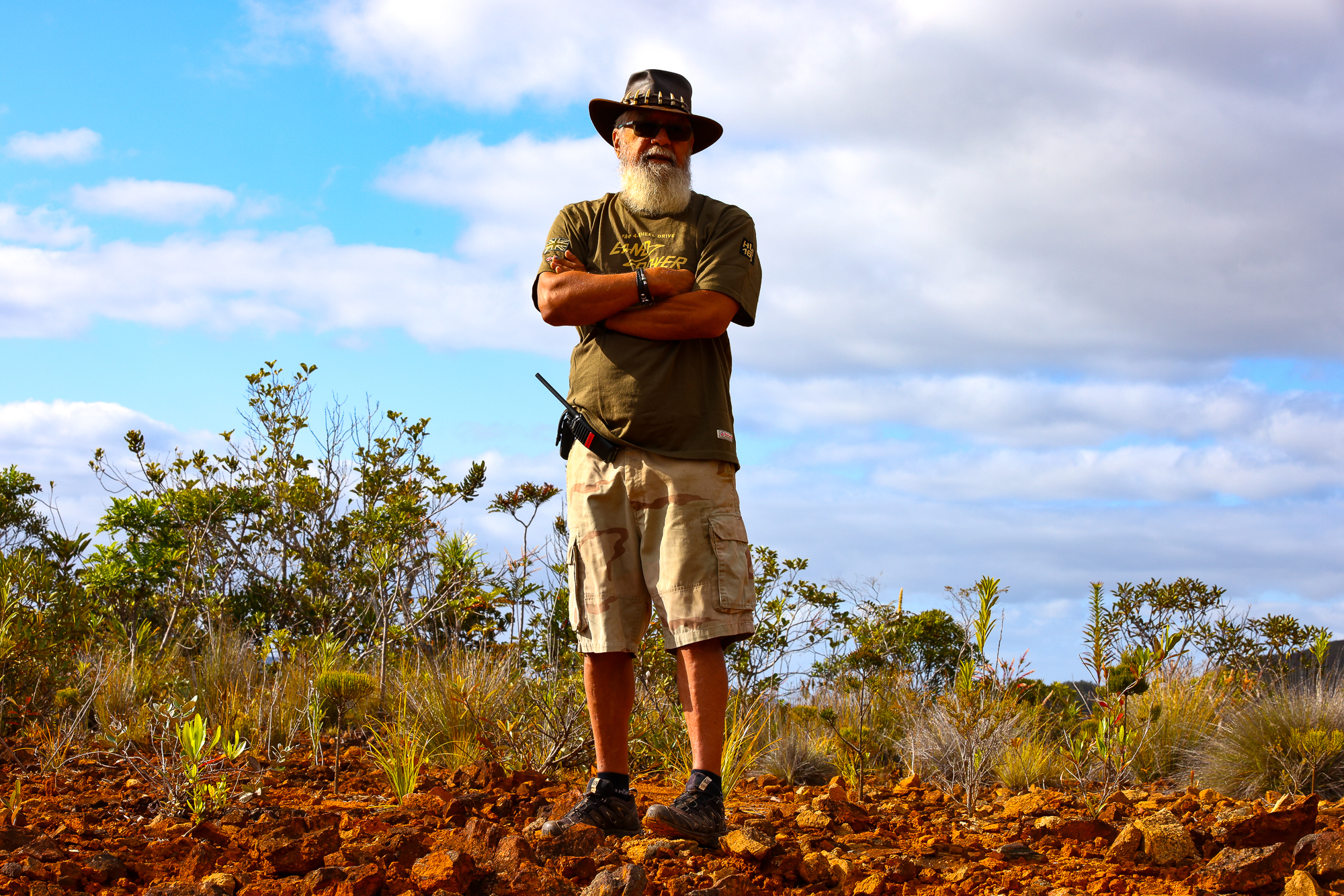

Exposure Therapy

Words Lester Perry

Images Sam Horgan

Each time I head out for a big mission, I’m trying to answer the question: “what else is possible?”; trying to redefine what I can do; and maybe even find a limit to what I can do.

Riding mountain bikes takes on myriad forms. For some, it’s an artistic expression, flowing through trails and jumps, interpreting features in their own way, translating them into a kind of moving work of art. For others, riding bikes is more about the physical feeling: muscles, heart rate, breathing, focus and exhaustion. Some would call it “Type 2 fun”.

My riding life has been expansive: I’ve flowed through jumps, interpreted trail features and chased the clock racing down hills. I still enjoy all aspects of riding but, these days, I’m drawn to bigger and bigger days on the pedals which ideally take in hours of translatable single track.

When I was younger, a three-hour ride seemed impossible but, over time one hour of riding stretched to one and a half, then two, eventually three, then five, then 12. It’s been an evolution over 30 years, and while I’m pushing to find the limits of what my body can do, the more hours I spend pedalling, the more I realise the limits of what I’m capable of are really in my head; mental not physical. It’s a kind of exposure therapy that’s helped me redefine what I’m able to achieve on the bike. Add a bit more time to each mission, more hours, more climbing, more hike-a-bike, a little more of everything. The more we’re exposed to adversity and challenge, the more we can adapt and overcome it.

Generally, when out for a big ‘endurance’ ride, it’s not the body which fails first, but the mind. The mind puts in place safety measures and boundaries to keep our physical self safe, telling us we can’t go further or do more in order to protect us. I’ve found a huge learning is the ability to distinguish between my brain telling me I’m simply uncomfortable, and it telling me I’m actually in trouble, in danger, or perhaps even injured. If I’m sure I’m just uncomfortable and there’s no real threat to my wellbeing, it’s a case of reframing the pain as just information. Information that yes, I’m uncomfortable, but I’m not actually in real danger. Success is about adapting to discomfort and overcoming it in order to keep pushing forward, ignoring the brain saying we can’t, or shouldn’t, be doing what we’re doing.

Big rides bring a big appetite, and food brings comfort when you’re out on the bike for many hours. Food not only provides fuel for our endeavours but helps the brain stay sharp and able to make good decisions. Even having the sharpness to know the difference between being uncomfortable and being at risk. A hunger bonk in the middle of nowhere can be the start of bad decisions and the slide to disaster.

The old saying, “suffering shared is suffering halved” is absolutely applicable here. A multi- day mission seems so much harder alone than when it’s shared with friends. Take the Kahurangi 600 ride I outline elsewhere in this issue; if I’d done that trip by myself, it would have felt like such a huge undertaking with much higher consequences if things went sideways. Sharing the trip with mates made it seem so much more approachable and achievable; much like most things in life.

Each time I head out for a big mission, I’m trying to answer the question: “what else is possible?”. Trying to redefine what I can do, and maybe even find a limit to what I can do. Obviously, it’s a balance between trying to go big and being underprepared, stupidly putting myself at risk, and stepping things up each time, exposing myself over time and taking things up a peg rather than just trying to ride headlong toward a limit to try and break through. That would likely find the limit, but end in tears.

Ultimately, I’m finding that big rides are more than just hours on the bike and kilometres under the tyres. They’ve become a practice in resilience, patience, and redefining what’s possible in other areas of life.

Bike Town

Words & Illustration Gary Sullivan

There are numerous things to note about life in a bike town.

Many you might expect. More bike shops, and better ones, than you would normally see in a regional town. There are many bike-related businesses located in the town for obvious reasons. Distributors. Designers. Skills teachers. Trail builders. In the example I live in, there are even two suspension specialists.

All these activities are here in my hometown because right on the edge of the joint there is a forest full of trails.

What you may not expect, and this is a feature of town that still amuses me after a quarter century of living here, is that almost all professional relationships are with fellow bike riders. And not because they are selected on that basis. The odds are that if a professional chooses to live here, the outdoors will be a big factor in the reasons why. And, if you are going to be an outdoors person around here, there is a solid chance you will be some sort of mountain biker. So, it follows that many contacts in the day-to- day are also likely to be seen out in the trails.

The first professional I encountered when we moved here, while we were still living on and off in a campground, was a doctor. I went to see her because I had munted my shoulder by going over the bars and had the extreme good fortune to get an appointment with a woman who has become a great friend. I knew she was likely to be a great doctor when she listened to my tale of woe then said, “that isn’t so bad, check this out” and proceeded to pull her shirt aside so the row of screws in her clavicle popped up in clear relief. She had busted herself mountain biking. For the 27 years since then, we have compared notes about our rides every time I have needed medical care.

In that time, I have also become acquainted with accountants, bankers, lawyers and physiotherapists, all of whom are dead keen mountain bikers.

Not to mention the nurse, the radiologist, the aneasthetist, and the emergency department doctor who dealt with me on one incredible visit to the hospital. All mountain bikers. My get-up made it obvious what I had been doing to snap my clavicle, but the novelty was talking to a series of people who wanted to know which trail, and where on the trail, and oh yes, that bit. They knew exactly where I had binned it.

The latest example of this trend is another medical professional.

When I got on her roster she had just moved here. When we met, we discussed the marvels of the forest, among other aspects of her new hometown.

She reckoned she loved the forest but couldn’t imagine going in there on a bike – too dangerous.

I only get to see her once or twice a year. Around the time of our second or third appointment, it turned out that bikes were now on the agenda, and she was riding a few of the forestry roads with her crew and really enjoying them.

The next time the Forest Loop was the favourite.

On my latest checkup, I learned that they had moved on to full suspension bikes, and were loving Grade 3 trails, like really fizzing about a couple of them.

It is currently pollen season, and she has really bad hay fever. She reckoned if she had known how bad the pine pollen was, she might never have moved here.

But, with those trails right next door, there is no way she would move away now!

Bridgedale MTB Socks

Words Lester Perry

Images Thomas Falconer

RRP $2975

Distributor Shimano NZ

Socks are often overlooked when it comes to mountain biking attire, but with our feet firmly planted in stiff riding shoes for hours, perhaps they deserve a little more attention.

Bridgedale, a company from Newtownards, Ireland, has been crafting socks for over a century. Their journey began with socks for the army during World War I. Bridgedale’s focus on creating the best outdoor activity socks ensures that they pay meticulous attention to detail.

Bridgedale’s MTB socks are engineered with advanced cushioning strategically placed in key areas. The asymmetric design utilises cushioning in specific areas for each foot, while the Vibration Damping Footbed employs a unique padding to reduce pedal chatter and trail vibrations. Padded zones around the outside of the foot, ankle, and along the Achilles provide additional warmth and impact protection. Bridgedale has even developed a new Underfoot Toe Seam for this range. By moving the toe seam to the underside of the sock, they’ve added extra padding on top of the toes and increased protection against impacts in the vulnerable area.

Bridgedale’s FusionTECH process sets them apart by blending high-quality yarns and materials with the latest knitting technology. This ensures every sock is comfortable regardless of conditions. Summer-weight models use Coolmax for cooling, while Merino wool provides a soft feel, temperature regulation, warmth and anti-bacterial properties. The underfoot toe seam eliminates the cold spot across the top of the toes, an issue with traditional over- toe sock seaming. This choice of materials, construction techniques, and the availability of two different weights, ensure there is a sock in the range to keep your feet comfortable regardless of the terrain or the conditions.

Bridgedale’s new Off-Road Bike socks offer improved performance through enhanced fit and support. Utilising Lycra Sport, they provide a supportive compression fit. A structured Y-Heel band and elasticated arch ensure a close fit, eliminating movement and friction. This additional support and precise fit enhance foot positioning, stability, and balance, leading to greater bike control.

I absolutely dig a fresh pair of socks. The plush feeling wrapping around your foot is so damn luxurious. This was certainly the case when I slipped on a pair of the Bridgedale Midweight merino socks. Initially, they felt great, providing a tangible feeling of support, especially around the footbed. On the bike, the socks offered ample support and stayed up – slipping down is one of my pet hates! After several rides, including a long four-hour pedal, the socks performed well without bunching. This was achieved via the asymmetric foot-specific design which eliminates friction from cycling shoes and provides better protection than a regular sock. The moisture management wicks any dampness away effectively, keeping feet dry in both warm and cool conditions by controlling heat and sweat.

After several washes, the socks have remained in good shape. Another pet hate of mine is how quickly new socks can get destroyed by the washing machine. It’s super annoying when you drop good money on a pair and they end up out of shape after just one or two washes. Bridgedale’s range feels durable and they completely back their products with a Lifetime Guarantee. This guarantee covers any defects in workmanship or materials, reflecting their 100 years of experience in sock-making. Knowing your sock game is dialled means you can focus on your riding experience. Don’t overlook your riding sock drawer – treat yourself to a good pair that’ll last the distance. The only downside is that these socks are quite spendy – but the quality, durability and guarantee makes them worth it. These socks are incredibly comfortable, far surpassing most others in my wardrobe. They’ve been on high rotation during house duties and on most rides – they’re that bloody good!

SRAM Motive Ultimate Brakes

Words Lester Perry

Images Thomas Falconer

RRP $1280

Distributor Worralls

In February 2024, SRAM dropped their fresh, brutally powerful, top-tier gravity brake; the Maven Ultimate. Although Maven was their second offering with Mineral fluid, the change to a Mineral brake fluid on this new flagship model hinted at a shift across SRAM’s brake offerings, and a move towards bleeding out DOT fluid systems, replacing them entirely with Mineral fluid brakes.

A year later, in March 2025, SRAM unveiled what many had suspected was coming: a simplified lineup of brakes based around a more user-friendly, and in most opinions, better-performing Mineral fluid.

I’ve been running a set of Mavens on one of my bikes for about a year and when I saw the Motive launch, I was keen to get on a set. Realistically, they’re squarely targeted at most of the riding I do and would suit another of my bikes perfectly.

This range revision plans to reduce the SRAM lineup from 27 models down to just ten, in a move to simplify and consolidate. The range is now split into three distinct streams: Maven targeting gravity, Motive targeting XC and Trail, and the DB series targeting power at a reduced price, thanks to fewer features and added weight.

The Motive series replaces two previous brake series from the SRAM range. The Motive brings almost the equivalent power as the now-discontinued Code, at a weight only slightly above the also-discontinued two-piston Level series, but in a Code-esque four-piston package. The Motive calliper is slightly squarer, and more boxy, than the sculpted Code, but houses the same size pistons so there are obvious similarities, although with new fluid comes new seals throughout the system.

The Motive is available in three tiers: Ultimate, Silver, and Bronze, like other SRAM brakes. All share more or less the same performance, with only minor tweaks distinguishing each level. The Ultimate has a crisp anodised finish, a swanky carbon lever with bearing pivot, and premium titanium hardware. Silver level goes to an alloy lever blade, with more basic stainless steel hardware, and less swanky finishing. The Bronze level is a little more no-frills with its bushing lever pivot, basic hardware and less premium finishing. The calliper has a fixed line fitting instead of the swivel banjo of the upper tiers. Differences in weight between the levels are subtle: Ultimate 265g, Silver 273g and Bronze 279g (rear brake, 1800mm hose, ready to ride but sans mounting hardware).

The Motive lever stays in line with the new ‘stealth’ styling, keeping the master cylinder and brake hose almost parallel to the handlebar. Thanks to the DirectLink lever, the feel is lighter than the Maven, right from the start, and has a more ‘normal’ SRAM feel of “what you put in is what you get out”; whereas the Maven’s SwingLink style lever has a cam that effectively multiplies your input power as you pull the lever, giving a different feel more suited to the demands of heavy braking over long periods. There’s no pad adjustment, which keeps things simple and lightweight, although basic reach adjust remains.

Expert Kit

The Expert Kit is a great way to purchase the Ultimate brakes. The kit includes everything you need to set up the brakes and maximise their performance over the long term. A pair of brakes, two pairs of sintered and two pairs of organic brake pads, 2x 160mm and 2x 180mm rotors, as well as all associated mounting hardware and mounts, and a multitool, complete bleed kit and oil. Essentially a one-buy solution to complete a top-tier Motive set up for XC or lighter trail use, that’s customised to the user’s specific needs.

The Ride

In my case, I threw the 180mm rotors on immediately with sintered pads. With it being the end of summer, and fitted to a 140mm travel trail bike, I opted to start with what I deemed the most powerful setup from the get-go and, if required, switch to a smaller rotor or organic pads from there. Needless to say, I haven’t changed anything.

It’s not normal for me to run a 180mm rotor up front unless I’m on a cross-country bike but, not having the option to go larger (at least out of the box), I was stuck with it. I’ve been surprised at how powerful the brakes are, even with the smaller front rotor.

The modulation is excellent, and lever feel is consistent throughout a descent. The ‘what you put in is what you get out’ feeling is certainly there and they feel like you can just squeeze harder and get more bite, however, there have been times I’ve noted I’m pulling quite hard when needing to haul anchor and stop quickly… like when one of your mates’ crashes right in front of you!

These brakes excel in the realms they’ve been designed for; cross country and trail. I wouldn’t think twice about putting these on a full-on XC race machine (in fact mine will likely end up on one) and in cases where weight is still relevant, i.e. on many ‘trail’ bikes, these would be ideal, possibly with a 200mm rotor up front, particularly if you’re heading toward the 90kg mark. For any enduro bike or rider purely focused on descending, where pedalling is just a means to an end, and where raw braking power is paramount, something less weight-focused like a Maven, or a new Shimano XT would be much more suited, particularly when trails get steep.

I think it’s worth noting here that bigger, or in this case, gruntier and more powerful, is not always better. Many people (myself included) are over-braked, choosing the most power possible rather than what’s actually best for them, often blinded by the power and large rotor sizes. The Motives have opened my eyes to some of the subtleties that make for better braking, not just having maximum power, but modulation, consistency and even the changes in using different pad compounds or rotor sizes, which help make it optimal for where, and how, I ride.

Leatt Enduro 3.0 Pant

Words Lester Perry

Images Thomas Falconer

RRP $199

Distributor BikeCorp

Launching in the moto world in 2015, Leatt first began to dabble in MTB gear with a range of helmets. By 2020, they had expanded their line to not only include helmets but pads, neck braces, shoes and apparel as well, offering a complete head-to-toe solution.

Now in its 20th year, and with numerous design awards under its belt, Leatt continues to go from strength to strength. In mid-2025, the brand announced its second quarter revenue was up 61%, its fourth consecutive quarter of growth, bucking the current industry trends in a big way.

They must be doing something right.

Through early 2025, on rides when I was reaching for long pants, a pair of Leatt Enduro 3.0 have been my preferred option. Particularly through autumn and winter, long pants win out over shorts for me. The increased protection they offer is nice, but it’s the ability to finish a filthy ride and just drop dacks and drive when I get back at the car—plus the minimal clean up required—that makes these a winner for me.

Although the name of these pants has ‘enduro’ in it, they’re far more than just an enduro pant. If there’s any time you’d wear long pants, these would do the trick, with one possible exception, which I’ll get to below.

With its regular, pre-curved fit, the pants are comfy on the bike, and there’s plenty of room for pads underneath without them being overly baggy. Long pants followed a trend of becoming slimmer and slimmer for a moment there but, thankfully, these are a bit more roomy. A Velcro waist adjuster on each side helps get the fit just right, and the medium size is in line with most 32” pants I wear, although if I were any larger, I’d likely need to step up to the large size, as I have the adjusters maxxed out as it is. The leg length is a fraction longer than ideal for me at 176cm tall, sitting partway down my ankle; my preference would be a little higher. Reality is, my legs are probably shorter than average for my height, so I’d imagine they’re optimal for most people, and the length isn’t enough to put me off.

The main fabric is lightweight and breathable, with a soft backing. Key areas are perforated to increase breathability. Around the inside of the thighs and across the seat is a three-layer, waterproof, breathable fabric. Helping keep you somewhat dry from ground water spraying up, while the pants remain breathable overall.

The Enduro 3.0 pant has pockets aplenty, ideal for big days out pedalling or lapping the bike park. Zipped thigh pockets feature on each leg and are large enough for a fair amount of cargo—they’re about the same size as a pack of jelly snakes. Each side also has more traditional, zipped, hip pockets; with an elastic key loop on the left side. The fifth pocket, located on the back of the waistband, is large enough to hold most cell phones—or some more snacks.

Out on the trail, the pants perform well and there’s nothing that stands out as a negative with the fit or function. The cut is perfect while seated and is fine for pedalling for long periods without excessive bunching. The fabric is a tad heavier than super lightweight trail pants, but this makes them harder wearing. The downside is that the overall weight of the pants is slightly higher, in part thanks to the fabric involved in the pockets. It’s not noticeable on the trail, but it’s worth noting these aren’t a super light trail pant, they’re sturdier and should last longer.

I wore these pants while in Christchurch reviewing the Specialized Levo 4, spending a day out pedalling around in what were near monsoon conditions. It was here I found a minor shortcoming of these pants: although the fabric repels water, it only does so to a certain degree. Thanks to the looped backing of the fabric, its overall weight and the pockets, when saturated, the pants retain more water than Leatt’s lighter-weight trail pants. They’re awesome for general use and on wet trails or in light rain, in part thanks to the waterproof seat area, however, when it’s absolutely pouring down, the lighter pants will retain less water.

So, who are these pants ideal for? I’d recommend these for anyone who has a focus on descending, who’s likely to need the extra protection they offer. Shuttle bunnies or eBikers, these will be right up your alley. If you’re into big, backcountry rides, the extra pockets will help you carry more and let you distribute the weight across your body. Just check the weather forecast before you leave home.

RockShox Reverb AXS B1

Words Lester Perry

Images Thomas Falconer

RRP $2975

Distributor Shimano NZ

There’s a fresh, new (and much-welcomed) dropper post in the RockShox range. The latest Reverb B1 broke cover recently, and I’ve been putting in some rides to get familiar with it. Here’s the lowdown after a month or so.

Firstly, somehow, unlike almost everything in life at the moment, the price of this new Reverb is actually less than the previous. Given its comparable simplicity, it’s also likely to save you money in the long run over that model, too. Go figure.

As with the Previous Reverb AXS post, there are no cables or wires involved. The Reverb B1 seamlessly slots into the AXS ecosystem. Simply drop the post into the bike, pair it up to an AXS controller, and you’re good to go. If you’re running an AXS drive train, it’s nice to be able to fine-tune which button on your cockpit activates the post through the SRAM AXS app; there are numerous combinations, although some make more sense than others.

From first glance, it appears the most significant change on the post is the moving of the actuator and battery from the head of the post down to its collar. This change, combined with a redesigned seat clamp, reduces the stack height by a fraction from the previous post. Most importantly, it brings the weight more centrally on the bike. The stack height is still above the market-leading One Up V3 post, although that’s cable-actuated, so not an accurate apples-to-apples comparison. Can’t have it all, I guess. The overall length of the post is shorter than previous Reverbs, though, bringing it closer to the competition so riders can now have more drop on smaller bikes.

There are seven drops available, ranging from 100mm to a gargantuan 250mm, stepping up in 25mm increments. From what I can find, 250mm is the largest in the market by 10mm. Previously, some head scratching, measuring, and diagram drawing (true story) would ensue as I tried to figure out what the longest drop I could fit on my bike would be in relation to my preferred saddle height; thankfully, RockShox has a handy calculator on their website to help determine the best option for any frame.

With the noticeable external changes, it would be easy to miss the other significant change in the post. A new ‘air over air’ design ditches the previous hydraulics in favour of positive and negative air springs. The two air springs balance pressure against each other as the post drops, effectively supporting rider weight on the positive air spring rather than relying on the hydraulics of the past. It’s no secret that RockShox’s previous posts had issues when their air and oil mixed, leaving a flaccid, squishy post in need of an expensive service. Long term, it remains to be seen, but if this system lives up to the hype, the days of unintended squish appear to be over.

The new air-over-air spring enabled a new feature, ActiveRide, which provides a small amount of vertical movement. At full extension, the amount of pressure in the post indicates the amount of travel available when fully extended. At the maximum pressure of 600psi (425psi on the 34.9mm post), it’s rock solid at the top of the stroke; the deeper into its stroke, the more travel or squish is available. It’s not a lot, but it’s there, and it increases if you drop the pressure in the post. Why build what is effectively suspension travel in the post? RockShox theory suggests that at full height, it enables a rider to stay fully weighted on the saddle over rougher terrain, which is particularly beneficial while climbing, as the rider can continue to apply consistent power without needing to disrupt their rhythm by unweighting. When tackling a particularly technical climb with steps or moves where dropping the saddle slightly is advantageous, the travel in the post again allows some damping against the terrain, helping you stay seated for longer. The conspiracist in me thinks that maybe, just maybe, RockShox couldn’t get the post to be rock solid when partially compressed with this new air spring, so they embraced the squish and gave it a name. Whatever the case, it seems to do what they claim, although I’m not so sure there’s a performance advantage on anything other than a hardtail.

The AXS button is now easier to reach while in the saddle, located at the top of the actuator (by the battery). It’s used to sync the post with its controller or as a manual actuator should a controller go offline. The post works with any actuator in the AXS ecosystem, including older paddle-style controllers and the now- common double-button pod controller.

With a claimed 60 hours of use from a full charge, or over 20 weeks for most of us regular folks, the battery will last a long time, but it’s easy to forget about it, too. If you’re running other AXS components, you’ll likely have the same battery elsewhere, so swapping a derailleur battery to a post, or vice versa, could be a saviour. I’ve seen this swap done on more than one race start line when a rider realised their derailleur was nearing flat.

Servicing on previous Reverbs was a total headache, and if an issue resulted in a complete rebuild, it was often cheaper to just replace the post with one other than a Reverb. This simpler design, combined with some forethought from the product team, means the B1 is completely user-serviceable. A simple ‘clean and grease’ 1-year service can be completed in literally minutes and requires only a few standard tools. No seal kits or oil faff required. The 2-year (600-hour) service is a bit more involved and requires some more specialist tools, but is still achievable for a competent home mechanic, thanks in part to SRAM’s in-depth online service manuals and YouTube tutorials.

Riding the new Reverb is not unlike the old version: push the button while you’re sitting on the saddle, and the post drops. Stand up, press the button, and the post shoots back to full extension. I’ve found myself reaching down at times to feel if the ActiveRide is doing anything, and sure enough, it’s going up and down slightly as I ride over bumps, although it’s hard to say if it’s offering any sort of advantage. There’s no rotational slop at all in the post and, so far, no sign of forward and backward movement either.

It’s nice to see RockShox are not resting on their laurels with their previous post, but recognising there were some shortcomings and developing something new in the form of the B1. They should get extra points for a complete revision rather than just minor updates. While it would be nice to see some fine-tuning of the drop available, like many mechanical posts, I guess that leaves something for RockShox to strive for in their next release. Maybe?

Given how simple the post is to install, and its price tag, it’s likely the post could be passed from bike to bike as its owner updates or changes their frame. However, with how new the post is to the market, it’s only fair to mention that no one’s 100% sure of its lifespan.

Bosch Performance Line CX Upgrade & Kiox 400C

Words Lester Perry

Images Thomas Falconer

RRP $2975

Distributor Shimano NZ

The electric mountain bike landscape moves at breakneck speed—literally. Often, it’s hard to keep track of the near constant changes but, as riders, we’re the ones who benefit from these shifts. Recently, Bosch eBike Systems has delivered significant performance upgrades. The German engineering giant has not only listened, but delivered exactly what riders want from modern eMTBs.

Performance Line CX Upgrade

The Performance Line CX’s (BDU384Y) upgrade to 100 Newton metres (Nm) of torque, represents a substantial leap from the 85Nm standard. The upgraded system now delivers up to 750 watts of peak power while maintaining support levels of up to 400 percent of pedal input. This power enhancement becomes available through a software update for the latest Generation 5 motors—excellent news for current Bosch Performance Line CX Gen5 owners, as it essentially future-proofs your eMTB investment.

The best part? This upgrade can be done seamlessly via the Flow app, where you can customise power delivery characteristics to match your riding style and terrain preferences. Another key element of this upgrade is the introduction of the new eMTB+ mode, which leverages advanced algorithms to deliver power with what Bosch describes as “sensitive precision exactly when the rider needs it”. This represents a significant shift from simply providing more power, to providing smarter power distribution.

I tested this upgrade on a Santa Cruz Vala during a trip to Silvan Forest MTB Park (featured in this issue). First, the update was simple via the Flow app, and what immediately impressed me was its intuitive nature—neither under- nor over-compensating, just enhancing my riding. It adapted to my cadence and provided a boost when needed over tricky obstacles. Some other eMTB systems I’ve ridden rely heavily on higher cadence, especially with lightweight models, but that’s not the case here.

The clear standout for me was the new eMTB+ mode. I didn’t need to toggle between any other modes at all. The technical difference between eMTB and eMTB+ is 15Nm of torque and a maximum power output difference of 150W. This difference is definitely noticeable, though as a heavier rider the benefits might be more pronounced for me. Riding in eMTB+ mode, the power delivery felt intuitive, and I appreciated that extra assistance and traction when hitting steep inclines.

This isn’t simply about raw numbers—it’s about the intelligent delivery of power that adapts to the rider’s demands with superior sensitivity.

Kiox 400C

The Kiox 400C represents Bosch’s vision for the next generation of eBike displays, moving beyond basic readouts to become the command centre for modern eMTBs.

Designed for integration into the top tube rather than handlebar mounting, the Kiox 400C offers a cleaner cockpit aesthetic while maintaining full functionality. The display features customisable settings and automatic brightness adjustment, addressing one of the persistent complaints about previous generation displays that struggled in varying light conditions. Tactile buttons provide direct control, while the optional bar-mounted Mini Remote ensures riders can maintain proper hand positioning during technical sections.

Perhaps most significantly, the Kiox 400C includes an integrated USB-C port, finally addressing the evolving needs of modern riders who rely on multiple devices during extended rides. The system also supports navigation functions, transforming the display from a simple readout into a genuine trail companion.

On the trails, the Kiox 400C remained perfectly readable in all light conditions, and perhaps its best feature was the dynamic screen cycling. Essentially, various Bosch Smart System algorithms detect what you’re doing—like tackling a climb – and automatically display the most relevant screen for that situation. I appreciated the simplicity of having the display show only the most pertinent data, which helped me stay focused on the ride itself.

The sleek display’s integration into the top tube creates a much tidier cockpit, which is certainly appealing from both aesthetic and functional perspectives. And having the Kiox 400C’s ability to charge USB-C devices like my iPhone during a ride proved super handy—no more dead phone anxiety on longer adventures.

The Bigger Picture

Bosch has taken a measured approach to rolling out these innovations. The Performance Line CX software upgrades are available now, accessible through both dealer updates and the Flow app for end users. This dual-path approach ensures accessibility while maintaining professional oversight for riders who prefer dealer support. The Kiox 400C, while designed for 2026 model bikes, offers retrofit compatibility with select 2025 models from participating manufacturers. The backwards compatibility of both the Performance Line CX upgrade and Kiox 400C is a solid addition—especially valuable if you’ve recently purchased a Bosch-powered eMTB.

The timing is particularly significant as the eMTB market continues its rapid expansion, with riders increasingly demanding sophisticated performance. These developments signal a new maturity in motor technology, where software updates can deliver meaningful performance improvements and where display technology finally matches the premium level of the power systems they control.

Patagonia Kit

Words Lester Perry

Images Thomas Falconer & Jamie Fox

RRP $229 Men’s Dirt Roamer Bike Shorts 12″ | $349 Dirt Roamer Liner Bike Bibs

Distributor Patagonia NZ

“Don’t buy these shorts”

In 2011, the brand Patagonia made headlines with their “Don’t Buy This Jacket” ad campaign in The New York Times. This was a shout out to anti- consumerism and their lifetime repair program that aims to ensure garments last forever, rather than be turfed on a rubbish heap and replaced.

Let’s rewind the clock back to the 1950s. Yvon Chouinard, a blacksmith, was producing a line of reusable Pitons (climbing anchor points) for local Californian climbers. By the early 1970s, climbing was booming and Chouinard pivoted, launching the Patagonia brand to offer climbing and outdoor soft goods with a focus on sustainability and durability, which he felt were lacking in the market at the time.

By the early 2000s, Patagonia was not only covering mountain sports but also starting to dabble in water sports, initially making some wetsuits for its staff. Then, in 2008, they launched a range of non-neoprene wetsuits, using limestone-based rubber, reducing dependency on petrochemicals and adhering to the company’s eco-friendly ethos.

In 2012, the team took another leap forward, offering an entirely plant-based rubber wetsuit range. By 2019, Patagonia was beginning to dabble in a different type of surfing: dirt surfing, AKA mountain biking, and by 2021 they had a tight but comprehensive range.

Around the same time as MTB apparel was breaking cover, Chouinard announced the transfer of Patagonia’s ownership to a trust and nonprofit to fight climate change, their $100 million+ yearly profits now going to environmental causes.

Drawing on experience and technologies from their existing ranges, they now offer quality, durable and eco-conscious shred-ready gear at a price. They’re sticking to their tried- and-true block colours and aren’t diving too hard into the latest trends—no garish “this will last a season” all-over prints here; just dependable, timeless silhouettes and colours.

There’s a reason Patagonia has been referred to as “Pata-Gucci”: their gear trends towards the premium end of the spectrum, not just in quality, but in price. If you can look past the price tag, there’s a lot on offer with Patagonia MTB gear, but you need to be prepared to take advantage of what’s on offer to really get the most from your investment. It requires a mind shift to buck the current industry trend of fast fashion. First off, if it doesn’t live up to the hype or expectation, take advantage of their “Ironclad Guarantee” for a refund, replacement or repair. Ripped a hole in a crash? Worn something out? Check out their free repair program, and you can either DIY repair with a patch kit—which they’ll send out—or send your gear in for repairs.

Patagonia’s strong environmental and social stance steers each decision made during garment production. Beginning with the goal to create better gear that lasts longer, meaning consumers buy less of it. With a key business goal being “cause no unnecessary harm”, their efforts to reduce environmental impact sometimes seem counterintuitive, but I guess this proves they’re walking the talk. Prioritising recycled, organic and plant-based materials, over 80% of Patagonia’s range is Fair Trade Certified, and their factories ensure staff receive a fair, legal wage and working conditions. Each part of their supply chain is optimised to ensure minimum environmental and social impact, while publicly available data ensures transparency, keeping them accountable.

Back to the MTB range. Split into two streams, the “Dirt Roamer” is lightweight, breathable and designed for big backcountry days in the saddle, while the “Dirt Craft” collection puts more focus on durability and less on lightweight, lending itself more to heavy-trail and bike park use.

Men’s Dirt Roamer Bike Shorts – 12″

Slicing open the package, if I didn’t know better, I’d swear I’d been sent a pair of board shorts. Fortunately, I do know better, and what was in the package was in fact a pair of Patagonia Dirt Roamer 12” bike shorts. My first impressions were about the short’s weight, or lack of it, and their construction. Similar to their boardshorts, the stretch fabric is seam- welded rather than sewn, keeping the weight low and comfort high with no stitched seams rubbing.

The fit is ‘regular’ and true to size. I wear 32” pants across most brands, and these 32” shorts are right on the money. There’s an adjuster to customise the waist if required. Lengthwise, these sit partway down my kneecap, an ideal length for pedalling with or without pads.

Initially, I thought the pockets were a bit odd. Rather than being a more traditional ‘hip’ pocket, these are lower down the leg on the thigh; not wrong, just different. A zipped opening keeps belongings in place, and there’s plenty of space to load them up. Internally, there’s an envelope-style flap that gives access to pockets of a liner short. Clearly intended to be used with the Dirt Roamer Liner Bibs, the opening lines up perfectly with the liner’s cargo pockets. This is something unique that I haven’t seen before, and ideal if you’d rather stow gear in the liner, with it being firmer against the leg rather than looser and able to move around in the pockets of the baggy outer shorts.

The lightweight fabric breathes well and feels soft against the skin. As they say on the tin, these are a trail short designed to pedal in, and they’re ideal for this. I’ve put in some decent 3+ hour rides in them, and at no point did I find them lacking. The fit was spot on, just baggy enough not to appear too XC-like, but slim enough so as not to snag on the saddle or flap around unnecessarily. The welded seams look like they will continue to be sturdy and secure, and as long as the fabric continues to be wear-free, I’d see these shorts lasting a long, long time.

Men’s Dirt Roamer Liner Bike Bibs

I’m a huge fan of a bib-style liner, but not all are created equal. I’ve purchased no less than three pairs which, after a couple of wears, have remained in the kit drawer, just not quite right. There’s a lot that can go wrong during the design and construction processes of bibs; get one wrong and they won’t be OK to wear for lengthy periods. Fit is paramount and nailing it for all body types would be near impossible—instead, design for the middle of the bell-curve and hope for the best. The layout of the panels, straps, and their associated seams needs to be just right to get that Goldilocks fit. If the seams aren’t in the right place, not only will the fit be off, but the wearer will probably get rubbed the wrong way. The chamois choice is an area a lot of liners fall short: too thin, too thick, not the right shape, not secured in a rub-free manner; there’s a lot to consider.

The Patagonia Dirt Roamer Liner Bib shorts fit me exceptionally, fitting my middle-of-the-bell-curve, medium-sized frame to perfection. The body of the bib is lightweight, breathable, and extremely stretchy; all edges are nicely welded flat. All the stretch involved means that at least the top half of the bibs should fit a wide range of heights. On the centre back is a single vertical cargo pocket, sized to fit a water bottle.

In keeping with Patagonia’s eco-ethos, all fabrics involved are made largely from recycled nylon. Downstairs, the body of the shorts is made from a power-stretch knit fabric for a comfy, taut, supportive feel. Breathable mesh panels and cargo pockets feature on each thigh. The laser-cut leg openings have a couple of rows of silicone, which, when combined with the power-stretch fabric, keep the legs nicely in place.

The Italian-designed, 3-layer chamois is a quality addition, as it should be for the price. It’s a nice medium thickness, which I’ve found offers a good level of padding and breathability, remaining chafe-free over lengthy rides.

Temperature regulation is key when running a bib liner with outer shorts; too hot, and sweat adds to chafing and discomfort. These bibs breathe well overall, keeping the temperature in check and comfort consistent, although I did find the upper body somewhat clammy at times when sodden with sweat.

These bibs are ideally combined with the Dirt Roamer shorts to take advantage of their pass-through pockets, giving ample storage across both shorts for any-sized outing. These are one of the more expensive liner options on the market, but considering their fit, chamois, and overall performance, not to mention the repair program, they’re good value in my book and should last many seasons.

Overall thoughts

I’ve been super impressed and quietly surprised by these shorts and bibs. This isn’t a case of a massive clothing brand just throwing their label on an underdeveloped, off-the-shelf garment, but a case of careful forethought, design and manufacture. A big blue sign approved green tick from me. Although they perform exceptionally, it’s up to a buyer to determine if the after-sales service and manufacturing ethos is worth the price of admission.

If you’re a keen trail rider who’s after top-tier, long-lasting shorts and liners, then look no further; just be sure to get the most out of them by using the repair service if needed.