The Mackenzie Race

Words & Images Supplied

The Mackenzie, brought to you by Devold, is back in 2025. After a successful inaugural event, held in April of this year, the 2025 edition looks to be bigger and better than ever. Set in the stunning Mackenzie Region of the South Island, there are multiple distances to choose from, allowing for a day full of adventure for all levels of experience and fitness.

The Mackenzie race is a resurrection of a past event organised by Peter and Margaret Munro. The ‘Around Lake Tekapo’ bike race attracted up to 1500 competitors back in its day, and saw riders loop the lake early in the winter months. With a new team organising this event, and with the support of the Lake Tekapo community and previous organisers, the event has been reinvented with new course options and an autumn date.

The theme of The Mackenzie is an ode to the history of this awe-inspiring location. In 1855, Scottish shepherd, James Mackenzie, came across this incredible district while trying to hide flocks of sheep that he had rustled with the help of his loyal dog, Friday. He was eventually captured and rumour has it that Friday continued to drive the flocks of sheep—even without his owner! What happened to James Mackenzie after his capture rivals any movie plot. Initially, he managed to escape, walking 100 miles to Lyttelton before being recaptured. Over the next months he escaped multiple times, eventually being put in irons. After finally being sentenced to hard labour for five years, he only served nine months before being pardoned due to an apparent miscarriage of justice. Upon release, James set sail for Australia and that is the last we know of what became of this legendary outlaw.

The iconic dog statue in Lake Tekapo is a tribute to all our working dogs, and sits proudly overlooking the lake. The Mackenzie District is named after James Mackenzie, and The Mackenzie race pays tribute to all the legendary shepherds and farmers that have nurtured this district ever since.

‘The Drover’ is the biggest race on the day and takes you on a journey to two of the most iconic lakes in New Zealand; Lake Pukaki and Lake Tekapo. The course utilises the unique features of this landscape; the canals that cut through the land, the turquoise hues of the lakes, and the mountain views all around —including New Zealand’s tallest mountain, Aoraki Mt Cook. For this day only, you will have access to private high country stations, allowing you the opportunity of a lifetime to cycle your way around this incredible location.

‘The Muster’ is a 92km adventure that is the full loop of Lake Tekapo. This is the most popular event on the day and riders have almost ten hours to ride around the lake. Godley Peaks Station is an absolute highlight with riders enjoying the high country station experience, including the wildlife and farm animals that roam amidst this vast landscape.

‘The Huntaway’ is a shorter loop of the lake, starting on Godley Peaks Station. This is a great option for those not wanting to spend quite as much time on their bikes but still wanting this ‘once in a lifetime’ experience—and with 73km to travel this is still no easy feat and definitely worth bragging rights post-race!

The final two events are out-and-back gravel races, offering competitors a fast ride on the eastern side of Lake Tekapo. Riders can choose between the 78km or 34km courses, and eBikes are welcome to join the gravel and mountain bikes on both of these distances.

In April of this year The Mackenzie saw elite riders tackle the race, alongside first- timers. There were some fast times recorded, including Craig Oliver completing the full loop of Lake Tekapo in 3 hours and 4 minutes. With professional athletes already signed up for the 2025 race, organisers are excited to see what the field looks like on race day.

“It was amazing to see the level of competitors at the event this year,” says event owner and organiser, Kerry Uren. “To see elites on the start line, it definitely added to the excitement when we set them off in the morning.”

But it’s not all about elites at this race. “It’s really important for us to ensure this event caters for everyone,” adds Kerry. “The majority of riders in 2024 were out for an adventure, and soaked up the atmosphere and views throughout the day. It’s pretty special to be able to get access to this area, so that was a definite drawcard for most. I know riders are as grateful as we are for the landowners who allow access for the event.”

Scenic Sports Events ensure competitors are safe whilst out on course, using a mixture of experienced personnel to marshal and specialist water safety teams to assist with the river crossings. Creating a remarkable atmosphere was high on the list of priorities as well, with the aid stations and friendly crew adding to the fun and welcoming vibe. The Musterer’s Rest Aid Station was set up like a café; tables and chairs were available for a rest, while the crew cooked up made-to-order toasted sandwiches, as well as coffee and tea—all included in the entry fee.

“What makes this event so special is the atmosphere,” says Kerry. “There was a real camaraderie out on course with riders offering ‘cramp stop’, supporting each other through the rivers, and even helping fix flat tyres.”

The next event is set for 5th April 2025, and entries have been coming in from all over New Zealand—and the world. With less than six months to go, why not make this event your next autumn race, where you too can have your own #legendarymackenzie adventure to share with your mates for years to come.

Southern Legends: 100 years in one trip

Words & Images Jamie Nicoll

The St James area did not pull my strings until I bumped into Johno while on a bike launch assignment, checking out the new Hanmer Springs trails. My eyes were opened to yet another hidden world of magical riding and scenery to be treasured!

Johno is a pioneer of new trails and a visionary of our sport – in other words, he’s exactly the sort of person I try to find so I can tell their story. Johno works alongside Mark Ingles… yes, the legend himself. After losing his legs to frostbite in an alpine survival situation, Mark has gone on to inspire many generations through motivational talks and projects like this one; the development of the St James. This was to turn out to be a week of Kiwi legends! Johno and Mark are working together to breathe epic style into Hamner and the surrounding remote St James ranges. These ranges are steeped in history and the romance of a rugged life of working the land on horseback—and this is not just history but a present-day reality: I met a horseman out earning a crust through trapping and track maintenance.

This is a place where you can ride for miles and stay in huts; it’s basically an Old Ghost Road or Paparoa trail, except that it has always been there and therefore hasn’t received the marketing attention. All you need to do is look at a map, follow the dotted lines between huts and you are done; you have created your own hut-to-hut adventure on good trails and singletrack with epic views. This area sports a lot of good weather days too, which is worth noting in case you were planning to ride into the mist and rain elsewhere.

Now, I live in Motueka, and I like going places via routes less trodden, so I turned the key on the tried and tested, global-expedition-equipped Land Cruiser with a bike strapped to the back, and headed for the rough roads. From Blenheim, one can access a gravel road heading south 120 km through the Molesworth Station, NZ’s largest station, and the road to Hanmer Springs. The Molesworth road is gravel and remote but can be driven in any sensible car, and allows you to drop into the back of the Hanmer Springs township.

After two days of touring, we pulled the trucks up at Johno’s house for an evening of poring over maps. The next morning the plan unfolded, with Mark Ingles shuttling us out to the start of Fowlers Pass on the Rainbow Road while my trail building mate, Sam, and his brother, drove the two Land Cruisers into a side valley to set up a welcome camp at Scotties Flat hut.

Fowlers Pass has a lot going for it. It sits at 1296m altitude with a smooth singletrack climb and loads of promising and stunning terrain. This was the start of chasing Johno on his eBike for the day. With a good portion of the climb done, we rounded a corner and there was some real-life Kiwi-as-you-get, grey-bearded, Swandri-wearing, horse-packing dude cruising along beside his mount. His name was Sean. His horse has no name but carried the most basic of set ups, using sacks as saddlebags—I thought I’d hit my head and gone back in time! Sean spends 11 months of the year in the backcountry, trapping possums for fur and repairing trails so horses – and subsequently, bikes – can pass through unhindered. Sean is actively involved with a group that focuses on establishing and re-opening historic horse trails throughout the South Island. Man, did this guy blow my mind… legend!

Descending off the pass, tight schist-y singletrack turned and a smooth, narrow thread of trails snaked down the open landscape. This had me back in France, and the trails of the infamous Trans Provence race.

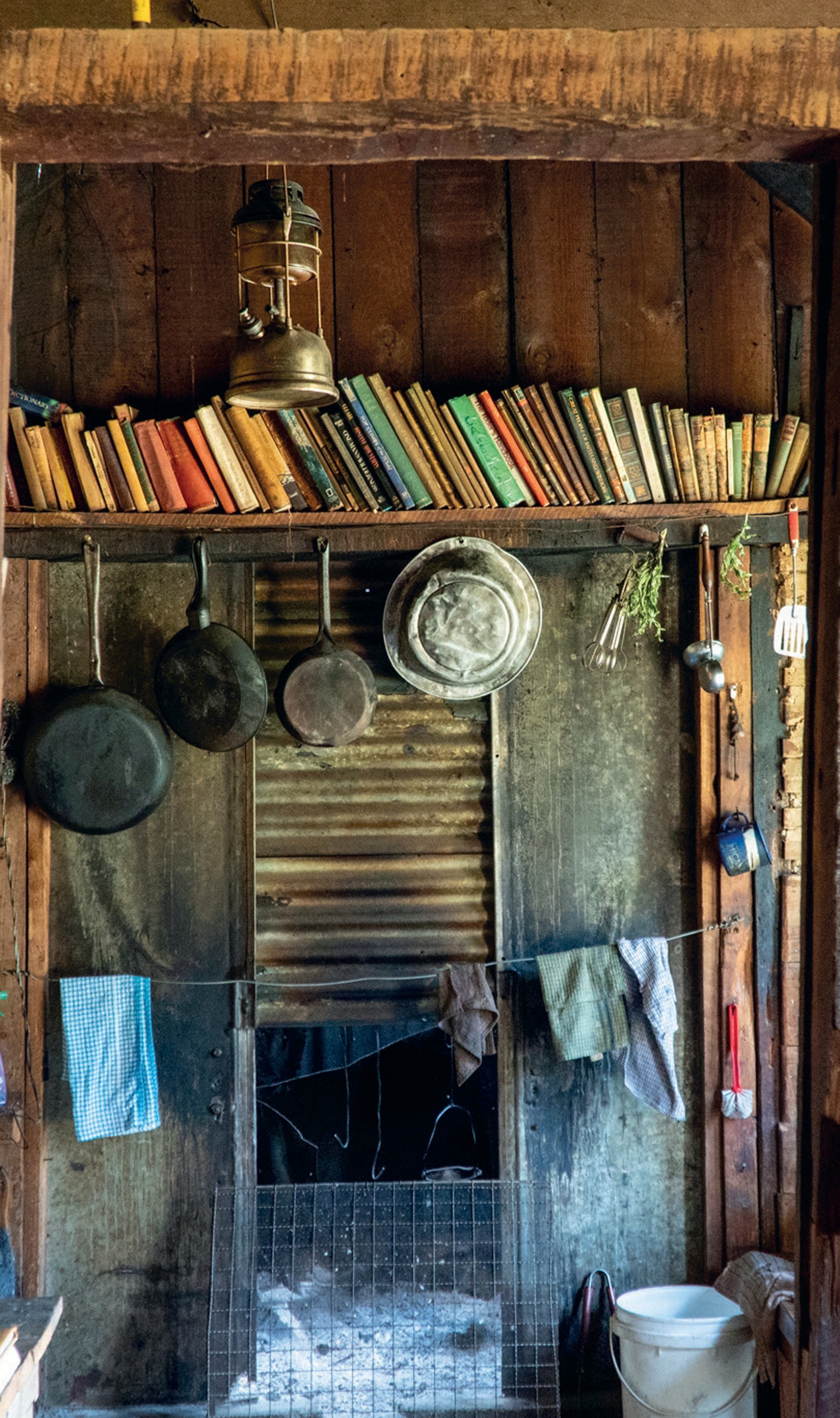

From a plateau meadowland, we peered down at Lake Guyon. Johno pointed out and explained more about the future trail development and links that will expand an already stellar array of backcountry and multi-day options. Think of it as a choose-your-own-adventure location. From the plateau, it was not far to the historic Stanley Vale Hut, dating back to the 1860s with remnants of wall paper and Mother Mary still hanging on the wall. I’d been told a story about some cyclists who had been snowed in at the hut, with Sean keeping them well entertained with stories over the bleak days!

The Stanley River, running south from this mountain grassland, boasts yet more singletrack. We generally maintained a nicely efficient pace, until we eventually climbed up out of the Stanley to ‘The Race Course’, something of a wide clay flat area. Again, you are privy to some of the most impressive views out west, up the Jones River and south down the Waiau.

Some 35km and six hours later we descended to Scotties Hut, down a newly cleared singletrack to a sweet welcome party of Sam and his adventurous kids. These are impressive kids—back home in Motueka the two of them spend days out playing in the forest while Sam is digging new MTB trails for a crust.

That evening, we headed to a remote “wild” hot pool not far from Scotties Hut. Wedged into a small side valley and beautifully located on the stream edge, the starry night above created a fine finish to a big day in the saddle.

Johno had only used 45% of his battery running on Eco for the day, but my legs were definitely spent. This was day four; bikes strapped to the Land Cruiser and headed out, we turned north towards Lake Tennyson and, more precisely, the rough road up to Mailing Pass. Standing at the 1308m pass we looked once more down to the beautiful grassland of the Waiau River flats. Johno pointed out the large pockets of beech forest nestled into the western folds and enthusiastically shared his trail vision for this descent, something worthy of a trip in its own right, once it is built.

With special permission from DOC, we were able to make a quick trip to look at Lake Guyon from the opposite angle. Standing at the Lake Guyon hut, we looked over this alpine lake up to the plateau edge I had looked down from only the day before. This gave me a good picture and understanding for the singletrack trail vision that would link these two tracks with not just old 4WD trails but outstanding singletrack terrain, making even more options for MTB backcountry adventures here!

Tired but stoked, we took shelter in the Island Gully hut in the middle of the scree-clad mountains of the Rainbow Road. Another night in the hills rounded out an epic adventure, rather than the all too familiar story of getting tired and over-focused on getting out. A fresh and happy bunch rolled back into the Motueka Valley with new and exciting trails under our belts and an eagerness to return for more!

Northern Lines

Words & Images Liam Friary

The Pacific Northwest has always held a certain mystique for mountain bikers. Its loamy trails, dense forests and mountainous terrain have been home to some of the world’s best shredders, and have helped shape the culture of our sport.

I was fortunate enough to take a winter hiatus earlier this year, to trip around some of North America. This part of the journey took me from the iconic trails of Bellingham, Washington, through British Columbia’s interior, ultimately landing us in Golden. The ‘us’ is me and one other – Chris Mandell. Just one video call led me to this situation; Chris was meeting a larger crew (travelling from other regions) in Golden for the 25th Anniversary of Psychosis, so I hitched a ride.

Bellingham served as our launch point; its reputation as a mountain bike haven is well- earned. The town sits nestled between the Salish Sea and the North Cascades, where trails seem to sprout from every fold in the landscape.

There’s a ton of riding options here and even if you spent weeks, you’d only just be scratching the surface. One of the main local riding locations is Galbraith Mountain. The network offers more than 65 miles of pristine singletrack that’s been methodically crafted over decades. Before heading north, we squeezed in an afternoon session on some of Galbraith’s finest. It was dry but the dirt was tacky, and the trails were so damn fun. Pacific Northwest trail builders craft with precision—berms and jump lines are dialled, but there’s also a heap of tight hand-cut singletrack. I was itching to get more trail time in, but we needed to gap it.

The van was packed. Two trail bikes, a DH bike, spare wheels, tyres, a heap of bike paraphernalia, clothes, some food and coffee and, after a quick homecooked lunch, we were set: ready to hit the road north. The border crossing at Sumas was relatively quick, and, soon enough, we were cruising through British Columbia’s Fraser Valley. The landscape gradually transformed from coastal rainforest to the drier interior as we pushed eastward. I was just trying to take everything in whilst also attempting to find an afternoon ride and dinner location. I wasn’t just a passenger, more like a co-pilot. We found a riding location to spin our legs, but it wasn’t really the mountain biking we were after as it was actually a cross-country ski course (in the winter, of course). We pedalled anyway as it was good to get the body moving again after spending a few hours in the van. We jumped back in and, within about ten minutes or so, we saw a heap of cars parked up at a trail head. Turns out that was a better location and had ‘real’ mountain bike trails. Oh well, that’s the joy of travel—right?!

After dinner in Kamloops, we pinned our first overnight stop to Salmon Arm. It’s a modest town on the shores of Shuswap Lake that’s quietly been developing its own mountain bike identity. The South Canoe trail network here is a testament to grassroots community building—local riders have turned hillsides into playgrounds, with trails that range from flowy cross-country to technical descent lines.

The morning light in Salmon Arm painted the lake in silvers and blues as we loaded up on coffee and breakfast sandwiches from a local cafe. After an hour or so of clearing the digital backlog, we were set for another day of road tripping. The air was crisp, typical of early summer in the BC interior. We surveyed Trail Forks and spotted a good trail en route. We drove the van up a fire road and parked at the trail exit. The climb up was peaceful, switch-backing through stands of cedar and fir with occasional glimpses of the Shuswap peeking through the trees. The descent was fast, flowing tight singletrack punctuated by natural rock rolls and root gaps that seemed purposefully placed by nature itself. I clipped a tree towards the end of the trail and catapulted myself off the bike. After a dust off, I fixed my bars and gathered myself before descending the rest of the trail. Stoke levels were high back at the van.

Golden was calling. But first: a short stopover in Revelstoke for lunch and multiple coffees. The urge to ride this iconic mountain biking location was at an all time high, but the timeline just didn’t allow for it, unfortunately. Here’s hoping I’ll get back there one day. Instead, we took in the historic charm of the town before hitting the road again. The drive east took us through some of BC’s most dramatic terrain—Rogers Pass cuts through the heart of the Selkirk Mountains, where glaciers still cling to peaks and the Trans- Canada Highway fits perfectly into the splendid scenery. The chat at this point was mostly about ski lines you could hit during the winter months. That’s certainly a trip for another time!

Golden appeared below us as we descended from Rogers Pass, nestled in the confluence of the Columbia and Kicking Horse Rivers, with Mt. 7 looming above like a staunch sentinel. The energy in town was all about the return of Psychosis. This is a race that had achieved almost mythical status in the mountain bike world, running from 1999 to 2008. After some dormant times, the race had been resurrected for its 25th Anniversary, drawing riders from here, there and almost everywhere to test themselves on one of the most demanding downhill tracks ever raced. Mt. 7’s course drops 1,200 vertical metres over seven kilometres, with some super steep gradients that would make a theme park seem lame.

The atmosphere in Golden was electric. The small town was buzzing, with bikes appearing from every corner. Our homestay for the event was an iconic local legend, Mark (Rabbit) Ewan. Rabbit had energy to burn and would not only house us but host us and get us anywhere we needed to be in Golden. It felt like we were with the mayor, as wherever we went with him in this small mountain town, he knew someone. His enthusiasm was infectious. Rabbit’s house was soon taken over by a flock of mountain bikers dossing down wherever space allowed. Thankfully, his wife and kids were out of town. A quick evening shuttle run was the order – I picked up the role of driver and the hoots and hollers on the way up were only louder on pick up at the bottom of the run. Rabbit took in some elements of the racecourse but wanted to venture off piste too. Dinner was served in the backyard, with bikes being tinkered with late into the night, thanks to the endless daylight that stuck around until 11pm.

Dawn was met with pancakes and maple syrup, washed down with coffee. Before long, we were driving back up Mt. 7’s access road, a rutted forest service path that twisted its way up. The view from the top is incredible and not only does it serve as a starting point for the riding trails, but a paragliding launch site, too. Columbia Valley stretched out below, with the morning mist still clinging to the river’s curves. Several runs later, the crew become a little more confident but there was still a nervous energy amongst them.

The race itself was a spectacle of human determination. Watching riders tackle the infamous ‘Dead Dog’—a steep, exposed section that had everyone’s hearts in their throats—was both terrifying and mesmerising. The level of commitment required to race this mountain at speed is hard to fathom, even for experienced riders. Between practice runs and race heats, the stories flowed. Tales of legendary runs from the day—and from the original Psychosis days—of broken bikes and broken bones, but mostly of the strong mountain biking community. Our crew all did well and kept their bikes upright and bones intact. The finish area party was strong, with music, beers, food and an electric atmosphere. This was all grass roots, with nothing flamboyant about it; as authentic as it gets. The crew were stoked to re-live yesteryear, reminiscing about the racing scene and how it reminded them that bikes have the power to bring like-minded people together.

Our final evening in Golden was spent at the after party, held at a local bar where racers, support crew and spectators celebrated hard with a 90’s punk band doing covers. It got quite loose as the intensity of the music ramped up – think: mosh pits, no shirts and an electric atmosphere that would rival some concerts these days. The return of this iconic event represents mountain biking’s raw soul. The stories shared that night weren’t just about racing, but the lifestyle that surrounds the sport, too. Psychosis is all about preserving a piece of mountain bike history and culture that often gets overlooked in the new era.

As we loaded up for the journey to my next location, Golden’s morning light painting Mt. 7 in alpenglow—it was clear why events like Psychosis matter. In an age where mountain biking continues to evolve and modernise, there’s something special about places that maintain their raw, untamed character. From Bellingham’s pristine trails to Golden’s rugged mountains, our road trip had traced a line through the sport’s past, present and future. The shared experience has become a core memory, at the heart of which is the strong and vibrant community that keeps the sport intact.

The Longest, Longest Day

Words Tom Bradshaw

Images Peter Wojnar

The idea was simple: fly to the Yukon, arriving at 11:59pm on Friday night. Greeted by the midnight sun of the summer solstice, we’d leave the bike bags somewhere and start riding. We’d ride the stunning Whitehorse trails until the 5pm flight on Sunday night, returning to Vancouver in time for work on Monday. No accommodation, no vehicles—just a big ride with plenty of stops and the occasional nap under the midnight sun.

It was ambitious to say the least.

Landing at Whitehorse airport ahead of schedule at 11:30pm on the Friday, we feverishly built up our bikes outside the terminal, in a twilight haze of disbelief and—to be honest—tiredness.

The Yukon is known for its remoteness; the gold rush, the Arctic Circle, and beautiful, expansive terrain.

It’s five times the size of New Zealand and, more than once, we would find ourselves “Yukon’d.” If you were to look up Yukon’d in the dictionary, it would be a verb describing the moment of realisation that, three hours into a climb towards a mountain top, it appears no closer than when you started.

The Yukon is less well known for its mountain biking, however, it is outstanding. The soil is a blend of water-sapping loam and near-sandy alpine dirt. The tree line stops at 900m of elevation, providing “easy” access to the alpine. The vastness cannot be underestimated.

Immediately, our plan was derailed. Unable to simply leave our bags in the bush by the airport as we had planned, we dragged them with us to the local bike shop. I-cycle, arguably the best named bike shop in the world, fortunately has a perfect covered patio where we left the bags. We began pedalling, into the darkness—and the rain.

As it transpires, even during the actual summer solstice the sun technically sets for about one hour. At this point it was 1:30am on the summer solstice and, because of the rain, clouds and technical twilight, our mood matched the unexpected darkness of the forest around us. There was no traffic and as we left the city limits, we realised how dark, wet and dumb this idea actually was.

Three hours later, at 4:30am, we finally broke the tree line. The 1000m climb had taken it’s time, as we paced ourselves and got lost a handful of times up the ever-expanding forestry road network. The visions I’d had of a four-hour-long twilight, painting the alpine and expansive Yukon landscape shades of a Picasso art piece, couldn’t have been more than a fever dream at this point. It was lightish, however, a grey misty cloud had settled, enveloping not only the sunrise but the view of Whitehorse entirely. At least we only had another 20 hours to go, a chance for the weather to clear.

As soon as we started heading downhill, the first bonk of the day disappeared. The low angle 800-metre descent was delicious, albeit spicy with the wet slick roots ready to catch a front wheel. The dirt was perfect, though, and held the moisture well.

The final 150 vertical metres was such a treat that we pushed back up and did it again. By the time we got to the bottom, it was 7:30am, and thoughts of hot, fresh coffee were pulling myself and Jacob to town. Fortunately Peter, who was also lugging around a camera, wisely told us we were being cowards and our short-sighted goal of hot coffee would add another 25km of road to our ride.

The mountains and their bike trails completely encircle Whitehorse. We had headed out to the west, and our next trail lay northwest of town. If Jacob and I were left to listen to our caffeine addiction, we would drop 400m elevation and have to ride back up the same road; it was a dumb idea inside a dumb idea. Instead, we listened to our bodies, and all promptly fell asleep. It’s amazing what 24 hours awake can do. We found a shelter, and passed out on the gravel like it was a California King. Some 20 minutes later, refreshed, we started climbing again—this time aiming for our second 1000m climb for the day: Whitehorse’s downhill track. The climb flew by; the proper daylight, improving weather and incoming fresh singletrack had us moving.

Haeckel Hill DH did not disappoint. Dropping in at about 10am we were treated to a handful of steep chutes with beautifully placed catch berms. The trail then went to that outstanding Rotorua- esque low angle, off the brakes gradient. We were riding like we hadn’t been moving for nearly 12 hours with 2000m of climbing under our belt.

After the 700m descent of beauty we had earnt a coffee. And a beer. This turned out to be a near-fatal mistake. Rolling back into downtown Whitehorse sometime after noon, we had been moving for about 12 hours and were all completely soaked. The bottoms of our feet resembled the contours on a topo map. They did not look pretty, nor did we. We were accepted to the local pub and found a table amongst the locals enjoying a rainy Saturday lunch. Fortunately, the people of Whitehorse could not have been more welcoming. They all seemed unperturbed by our soaking wet carcasses, and we celebrated the halfway mark by toasting to being inside and warm. The consequences of that lunch beer were almost immediate. It was all we could do not fall asleep in the warm, dry pub. Knowing we couldn’t afford to totally piss off the locals, we settled up and promptly fell asleep on the park bench across the road.

This was not the alpine wildflower bed sunshine nap I had envisioned when scheming this mission. But at this point, none of us could care less. Awaking to rain falling on us again, and seeing that it was 2:30pm, we decided we should really get going to climb up Grey Mountain, a 1400m mountain to the east of town.

Over the next three hours, we learned the hard way about the term “Yukon’d”. By 5:30pm it felt like we hadn’t even made a dent on the climb, however, it was starting to make a dent on us. We needed to stop to air our now trench foot-like feet every hour or two—the downside of our plan to only wear our riding gear on the plane. This travel light strategy was really starting to backfire on us as I considered pedalling barefoot for a spell. The fire road was pleasant enough, with a gentle gradient, and the three of us kept each other cheery while reminding each other of previous indiscretions over the past 18 hours. The animals of Whitehorse were clearly taking shelter, wiser than us; our only sighting was a small black bear, jumping out a few hundred metres up the road, glancing at us then deciding he had better things to eat than three smelly, tired, wet humans.

Fortunately, the higher we climbed, the clearer the skies got. The cloud broke as we reached the summit of Grey Mountain. It was 7:30pm when we were gifted our first proper view of the Yukon. The mountain had taken five or so hours to climb from town, but paled in comparison to what lay beyond. Mountains, lakes and the mighty Yukon river stretched as far as the eye could see. It was beautiful. And so was the descent.

Money Shot was the most technically challenging trail yet; steep, rocky and exposed as it descended through the alpine. Again, the descent gave us all a shot of life. All three of us rode like we’d just jumped off a chairlift, passing each other on inside lines and cackling at the trail. This was our first of two descents off Grey Mountain. We’d lost 600 metres on this descent and started climbing to the top for a second time, knowing midnight was getting close.

We knew we had to be at the summit by around 11:30pm. The light was fading and rain clouds were forecast to roll back in. We had ambitiously decided not to pack any riding lights, believing that “of course we won’t need them; it’ll be light the whole time”.

Regardless, we pushed on knowing this would be the final descent of our longest, longest day. We started climbing the final alpine ridge at 10:30pm. The cloudy, murky twilight wasn’t the hours-long beautiful golden hour sunset I had envisioned, but it was still breathtaking. The climb was also breathtaking. By this point, we had climbed well over 3,500m and ridden over 120kms on about 50ish minutes of sleep. The bonk was hitting us all hard.

It was only fitting that this final 1000m plus descent was called “The Dream.” A beauty; blue flow trail, hand-built by volunteers from the local mountain bike club, descended through the alpine back to the Yukon River and into town.

Naturally, we didn’t make the summit quite in time. As we dropped in at 11:45pm, the fading light and cloud made ‘The Dream’ a true and proper dream. Hooting and hollering like the delirious children we were, we scared any wildlife out of the way, the descent once again bringing us all to life. Twenty-four hours in, we were riding like it was lap one; the sandy alpine dirt providing unlimited grip despite the rain. The lights from town steadily got brighter as we got closer, and our grins were ear to ear.

As we rolled back to town at 1am, some 11 hours after we had left from our lunch nap, we realised how hungry and tired we were.

It’s fair to say we had drastically underestimated the logistics. I had planned this trip thinking we’d be riding through the hot summer sunlight, taking rests in fields of alpine wildflowers, and riding all the way through to our flight back on Sunday afternoon. Due to this overly ambitious plan, we had failed to book or bring any accommodation with us. We hadn’t really thought about that until this point, however, food was our number one priority. Whether you are in Whitehorse, Wellington or Warsaw, the golden arches of McDonald’s will always provide. The crispy, salty fries and magic Big Mac sauce filled a void we didn’t know we had.

Considering our options, sitting outside, soaked and bonked, we decided going back to our bike bags under the sheltered porch of the bike shop was our best move. And by god it was. To be honest, we probably could’ve booked a hotel, but we weren’t ready to drag our soaking wet carcasses back to society just yet.

Cozying up in a bike bag might not seem like the comfiest bed to you, if you’re reading this from the couch or the coffee shop, but at 1:30am in the twilight of a rainy Whitehorse morning, it couldn’t have been better.

A successful end to the longest, longest day ride. As the sun properly rose on Sunday morning, we sought shelter in the local coffee shop, promptly falling asleep again, but caffeinated, dry and relatively warm.

We spent Sunday testing out the local BMX track and jumps close to town, then rode back up to the airport, but only after a crucial stop to buy clothes for the flight home. Our strategy of packing only our riding gear had worked out so far, however, by now we were a biohazard. We would not have been allowed to board a commercial flight in the state we were in, so Walmart provided a pair of jandals and enough clothes to let us board the flight home.

Sitting down on the flight back to Vancouver, I felt relieved that the Yukon had let us get away with this atrocious lack of planning. The vastness was real, and a place I cannot wait to revisit with the bike—and perhaps a vehicle and accommodation. Nonetheless, we left feeling successful. We did it, but it wasn’t pretty. We had spent the entire midnight to midnight exploring the outstanding trails, people and town Whitehorse has to offer.

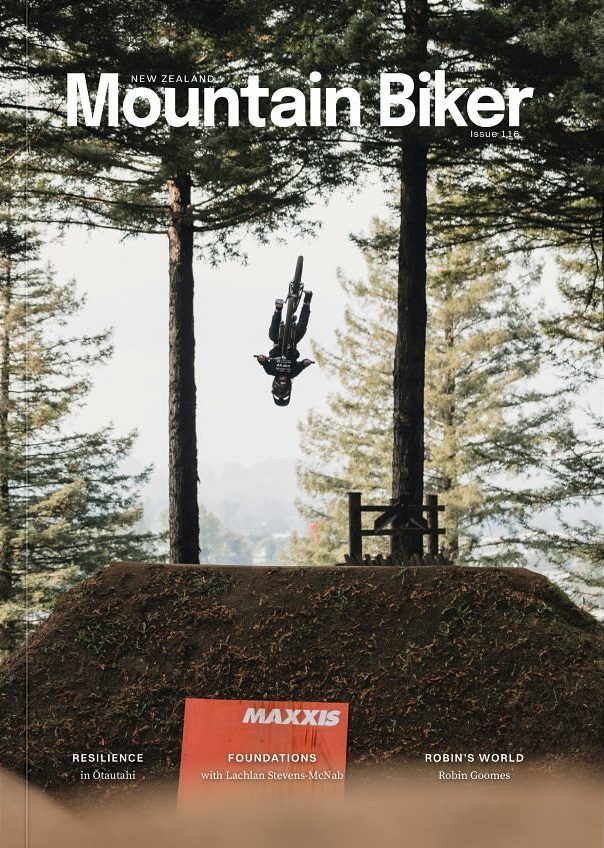

Resilience in Ōtautahi: Christchurch’s Mountain Biking Legacy

Words Lester Perry

Images Cameron Mackenzie

In the shadow of the Southern Alps, where tectonic forces have shaped both landscape and spirit, Ōtautahi Christchurch’s mountain biking community has written its own story of resilience.

In the shadow of the Southern Alps, where tectonic forces have shaped both landscape and spirit, Ōtautahi Christchurch’s mountain biking community has written its own story of resilience.

Like the native tussock grass that bends but never breaks in Canterbury’s fierce nor ‘westers, the city’s riders have proven time and again that adversity only strengthens their resolve.

The devastation of yesteryear has hardened city dwellers who have incredible forward momentum. These individuals are armed with spades and determination and, over the past decade or more, they’ve built new lines to prove their mettle on. Not only new lines appeared but new riding communities too and, nowadays, rider’s flock to Christchurch and its stunning surrounds to get a piece of the action.

The Port Hills, those ancient volcanic remnants that stand sentinel over the city, have always been more than just terrain. They’re the beating heart of Christchurch’s mountain biking culture. From the technical challenges of Flying Nun to the flowing contours of Anaconda, each trail tells a story. Simply ask around and you’ll hear rider’s tales of dawn missions before work, lights twinkling on helmets as they chase the sun up Mt. Vernon; and weekend missions.

When the Christchurch Adventure Park (CAP) emerged from the drawing board in 2016, it wasn’t just another bike park—it was a statement of intent. Heck, there was a ton of excitement in the air at the time and rightfully so. This would be the Southern Hemisphere’s first year-round chairlift-assisted bike park. It represented everything the community stood for: ambition, innovation, and that characteristic Cantabrian courage to dream big. The 358.5 hectare park became a testament to what’s possible when passion meets perseverance.

The 2017 Port Hills fires, that swept through CAP, could have been the end of the story. Instead, it became just another chapter in Christchurch’s tale of renewal. As the smoke cleared, revealing a changed landscape of blackened pine skeletons and scorched earth, the mountain biking community rallied. Volunteer trail builders worked alongside professional teams, adapting their designs to the new terrain. Where once there were forest lines, they created raw, exposed tracks that showcased the hills’ natural beauty. The park didn’t just survive—it evolved.

Today, Christchurch’s riding scene reflects this history of adaptation and growth. The city’s unique geography offers something for every rider. Beginners find their wheels at McLeans Island, where purpose-built tracks wind through river terraces. Urban warriors connect the dots between the city’s green spaces via an extensive cycle network that makes every ride an adventure. Intermediate to advanced riders push their limits at CAP, where world-class trails like Shredzilla and B-Line challenge even the most skilled athletes.

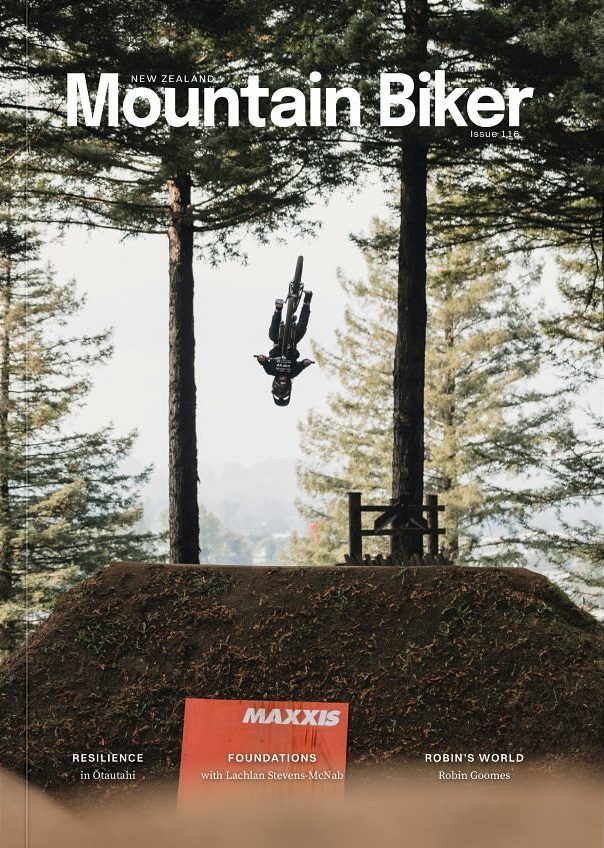

The highly anticipated Crankworx Summer Series is set to return to New Zealand in 2025, after the cancellation of the 2024 event due to the devastating fires in the Port Hills. The series will take place from 13th to 16th February 2025, with a new line up of events that will elevate the mountain biking experience for both riders and spectators alike, and will form part of the build-up to the first mega-festival of the Crankworx World Tour, in Rotorua from 5th – 9th March 2025.

The Ōtautahi Christchurch festival will introduce a new Freeride Mountain Bike Association (FMBA) Gold Level Slopestyle event, the first of its kind in New Zealand. The new course and competition is set to attract some of the world’s top Slopestyle riders and provide a pathway for emerging New Zealand talent. Alongside Slopestyle, the series will also feature Pump Track and Downhill, ensuring a weekend packed with action for spectators and athletes alike.

Beyond the established trails, Christchurch’s riding culture continues to evolve. Secret lines appear in forgotten corners of the Port Hills, carved by passionate locals who see possibility in every contour. Over the weekend, vehicles with bikes hanging off them head out of town with riders making the short trek to Craigieburn and Mt. Hutt, extending the community’s reach into the high country. Each new trail, whether sanctioned or social, adds another thread to the rich tapestry of Christchurch’s mountain biking story.

The city’s mountain biking infrastructure has become a model for urban planning worldwide. The Major Cycleway network, born from post-earthquake reconstruction, has transformed how people move through the city. Riders can now pedal from the International Airport to the Adventure Park without leaving dedicated cycling infrastructure – a journey that captures the essence of Christchurch’s commitment to two-wheeled adventure. What’s even better, is that you can store your bike box at the airport—perfect for a weekend riding getaway with no need for a car!

As the sun sets behind the Port Hills, casting long shadows across tracks both old and new, Ōtautahi Christchurch’s mountain biking community continues to prove that it’s not the challenges that define us, but how we respond to them. In the end, it’s not just about the trails – it’s about the people who build them, ride them, and keep coming back, no matter what nature throws their way.